Kaori Endo is a Textile/ Visual Artist who uses textiles, weaving, dyeing, and video to unpack the political relations rooted in the crafts, histories, and livelihoods within each place.

She examines the environment in which female factory workers were placed at that time through documents from that period and video interviews with a woman who worked at the factory, including the parachute from the Imperial Japanese Army sewn by female factory workers.

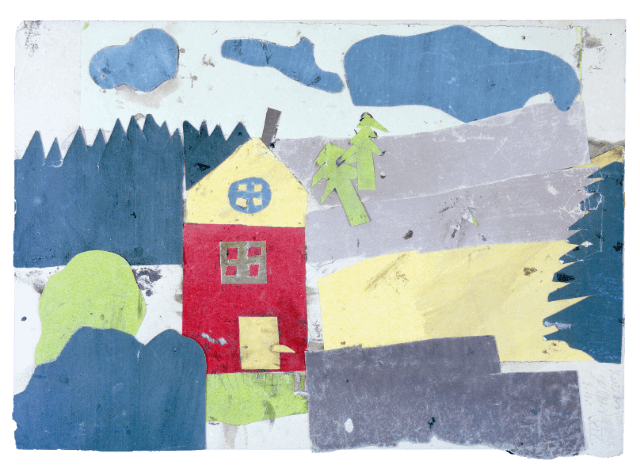

Exhibition 1

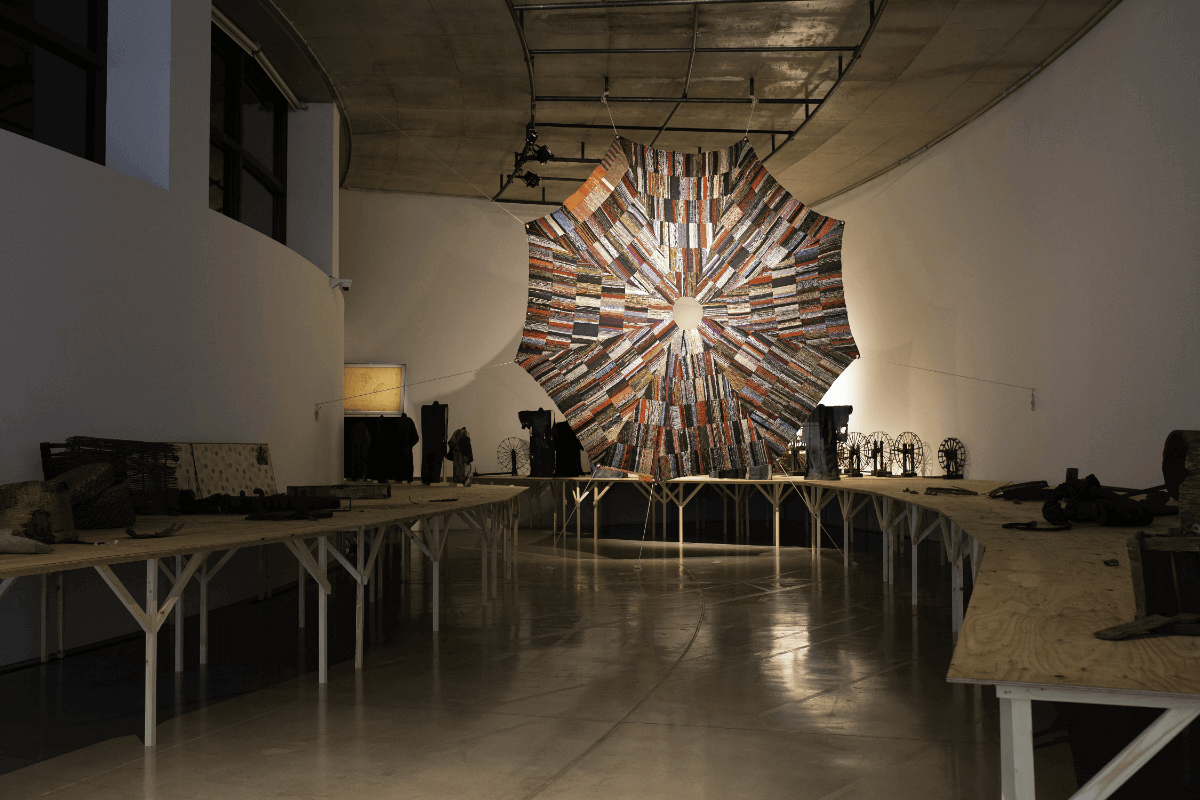

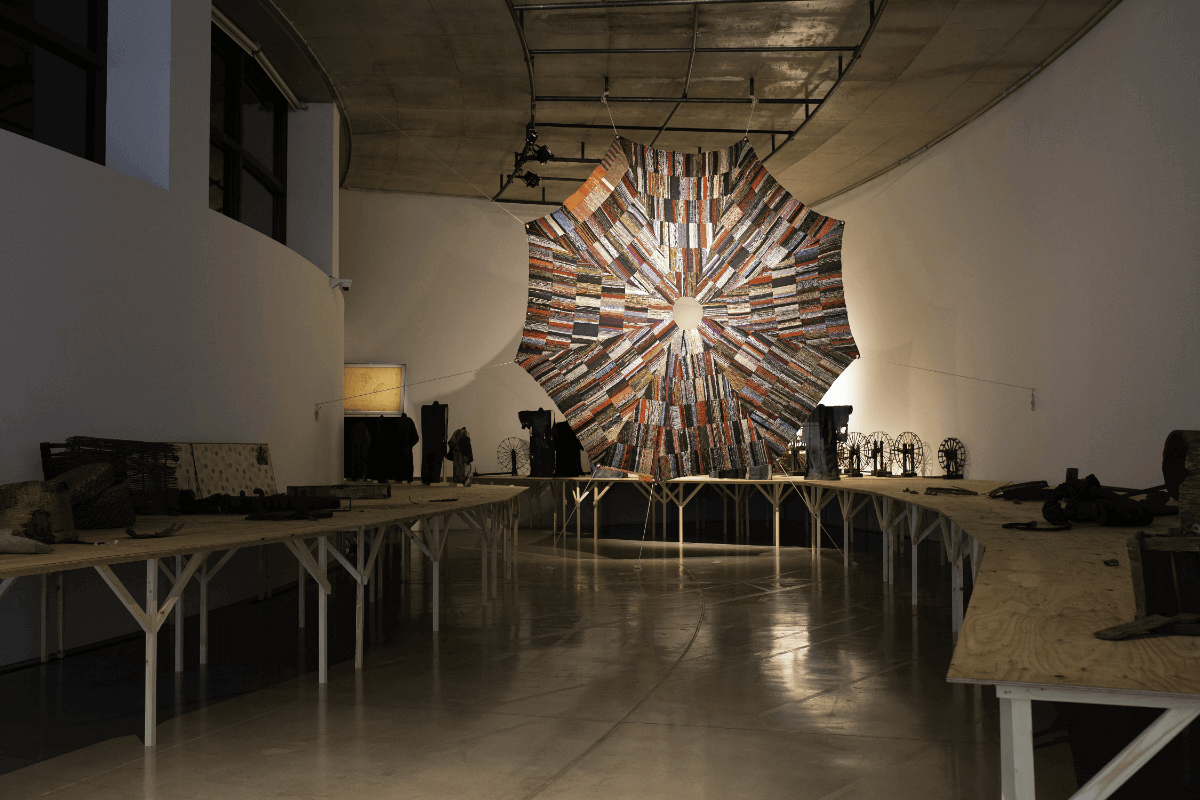

A Parachute from the Imperial Japanese Army

Kaori Endo

(Textile/ Visual Artist)

[Profile]

After graduating from the Okinawa Prefectural University of Arts in 2013, she studied at Ars Shimura under Fukumi Shimura (a Living National Treasure for tsumugi (pongee) weaving) in 2016. While traveling around the world, she has been working to expand the potential of crafts through her body by unraveling the relationships among local crafts, history, daily life, and politics. Recent major exhibitions include “Aichi Triennale 2022” at Toyoshima Memorial Museum; “Portraits of Ryukyu” at Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum (2021-2022); “Welcome, Stranger, to this Place” at Chinretsukan Gallery, The University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts (2021) and “The 13th shiseido art egg” at Shiseido Gallery (2019, Tokyo).

After graduating from the Okinawa Prefectural University of Arts in 2013, she studied at Ars Shimura under Fukumi Shimura (a Living National Treasure for tsumugi (pongee) weaving) in 2016. While traveling around the world, she has been working to expand the potential of crafts through her body by unraveling the relationships among local crafts, history, daily life, and politics. Recent major exhibitions include “Aichi Triennale 2022” at Toyoshima Memorial Museum; “Portraits of Ryukyu” at Okinawa Prefectural Museum and Art Museum (2021-2022); “Welcome, Stranger, to this Place” at Chinretsukan Gallery, The University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts (2021) and “The 13th shiseido art egg” at Shiseido Gallery (2019, Tokyo).

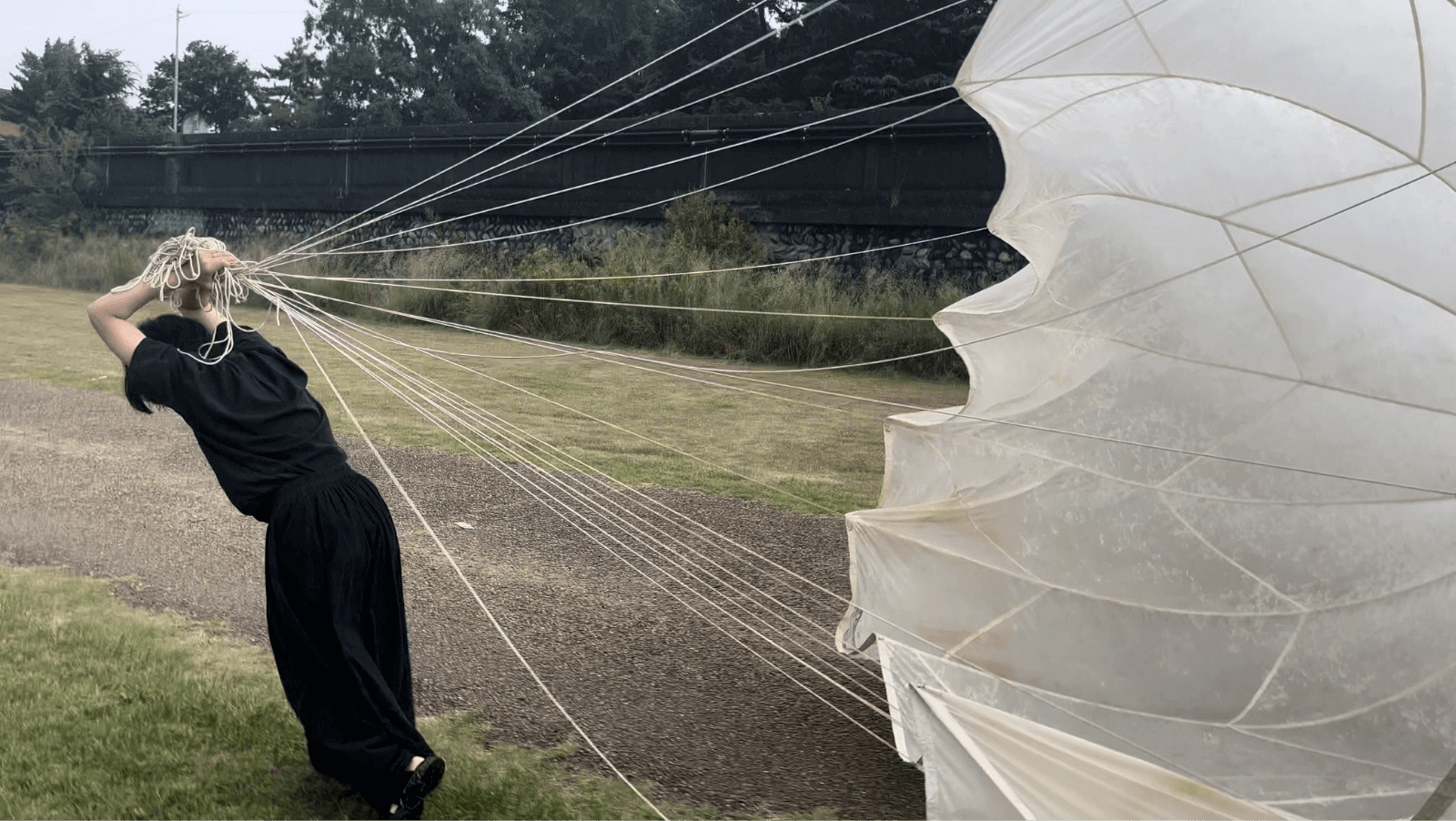

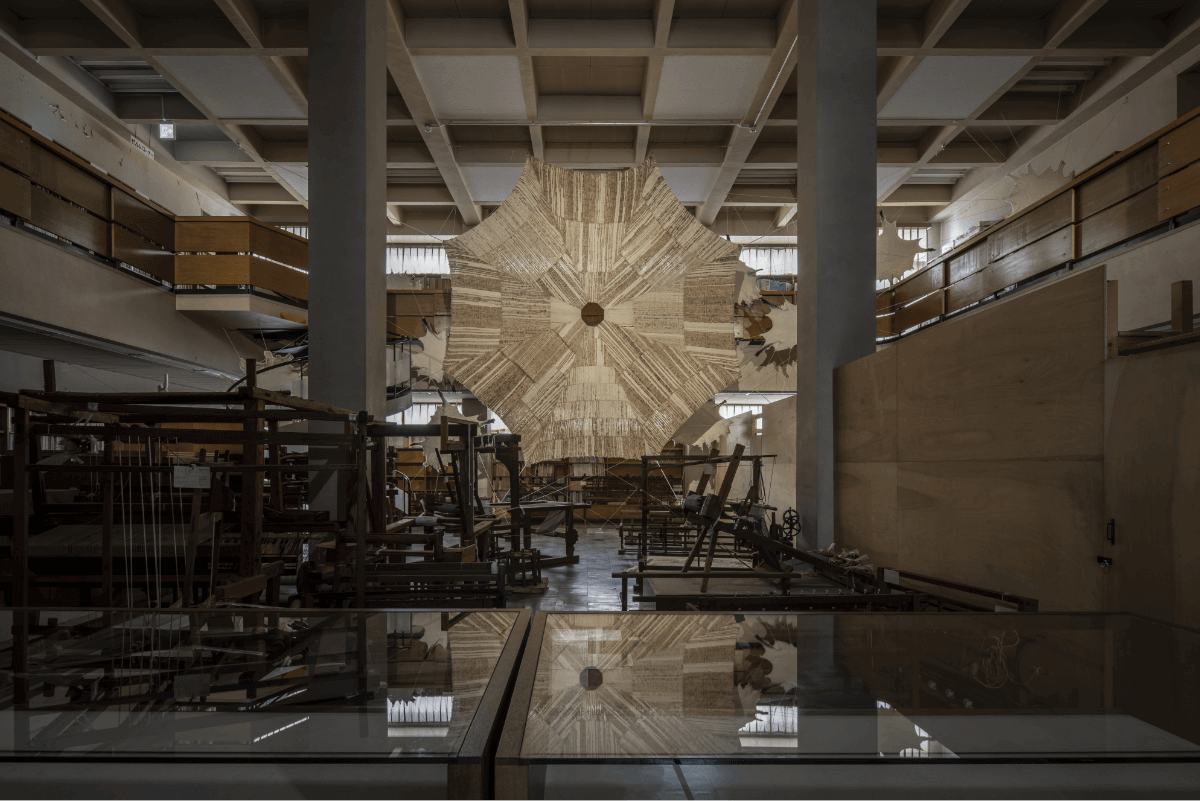

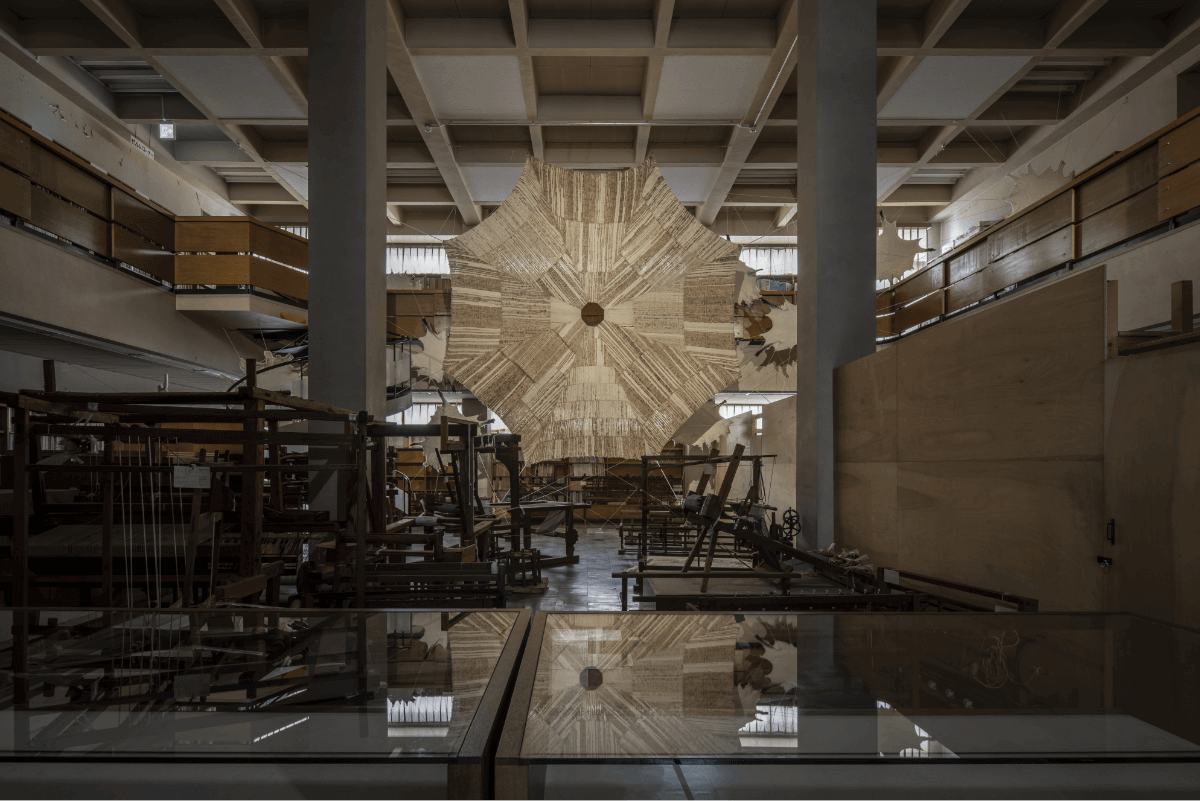

The location for this video work is the Kiso River in Ichinomiya, Aichi Prefecture.

On Tanabata Day of the lunar calendar in 2022, Endo walked with a parachute from the Imperial Japanese Army on her back. Female workers of the textile factory are known as “Orihime,” and the location is known as the site of Japan’s three most famous Tanabata festivals.

The area has long benefited from the abundant water flow and logistics of the Kiso River, and the textile industry continues to thrive. This region is the largest producer of wool textiles in the country. Sheep, originally not found in Japan, are imported and bred throughout the country as a national policy.They came to Japan because they were used as materials for military uniforms worn in Cold War zones.

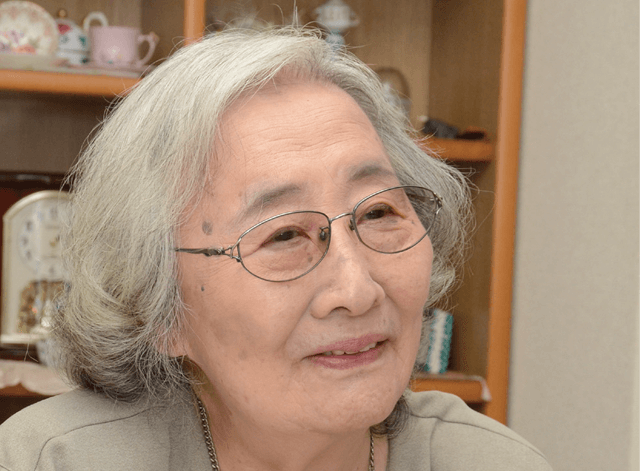

Endo spoke with a woman who had been working in a wool factory in Ichinomiya since then. She described her experience of sewing parachutes and balloon bombs at the wool factory during the war. Near the end of the war, she recounted that soldiers had given her a ceramic hand grenade when she had evacuated to a hole in a shelter dug to protect citizens from the war fire.

When iron was in short supply, potters across the country made grenades using local clays and glazes. These grenades, which were less lethal than their iron counterparts, were distributed to citizens in order for them to commit suicide and choose noble death.

However, she became worried, broke away from the grenade, and fled instead of entering the shelter.

The people in the shelter she was supposed to enter were hit by the blast, and most lost their lives. In interviews, the woman often repeats: “I survived because I was a wimp.”

Ichinomiya was the place where the suppression of hidden Christians was most intense in Honshu, the main island of Japan.

There, hidden Christians lost their lives because they refused to step on “Fumie,” a plate with the image of a crucifix or other Christian symbol, due to the strength of their faith and others committed suicide for the sake of the country by saying “Long live the Emperor!”

What is the connection between those people and the woman’s action of running away and surviving “because she was a wimp”? Are these things irrelevant to us living in the modern world? This exhibition reconsiders these questions regarding weakness, strength, and survival.

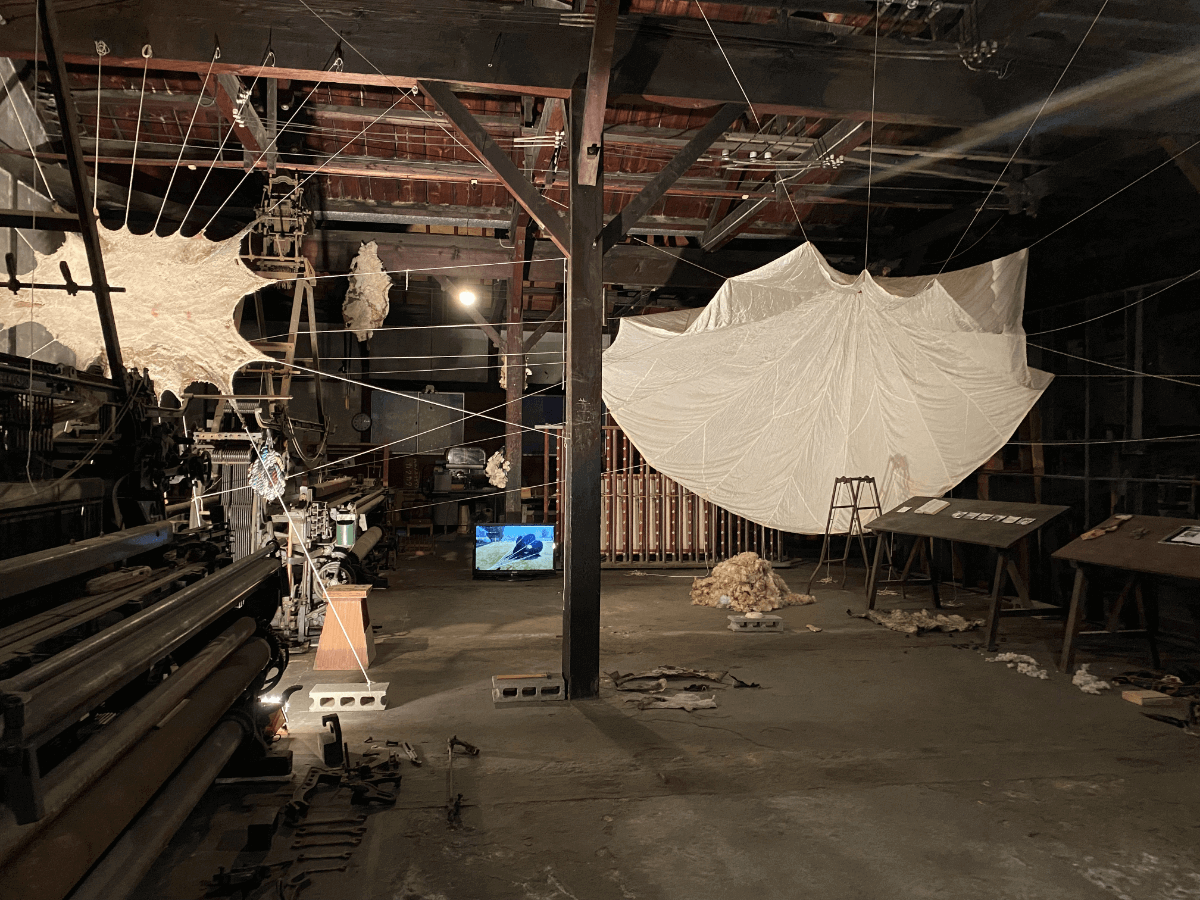

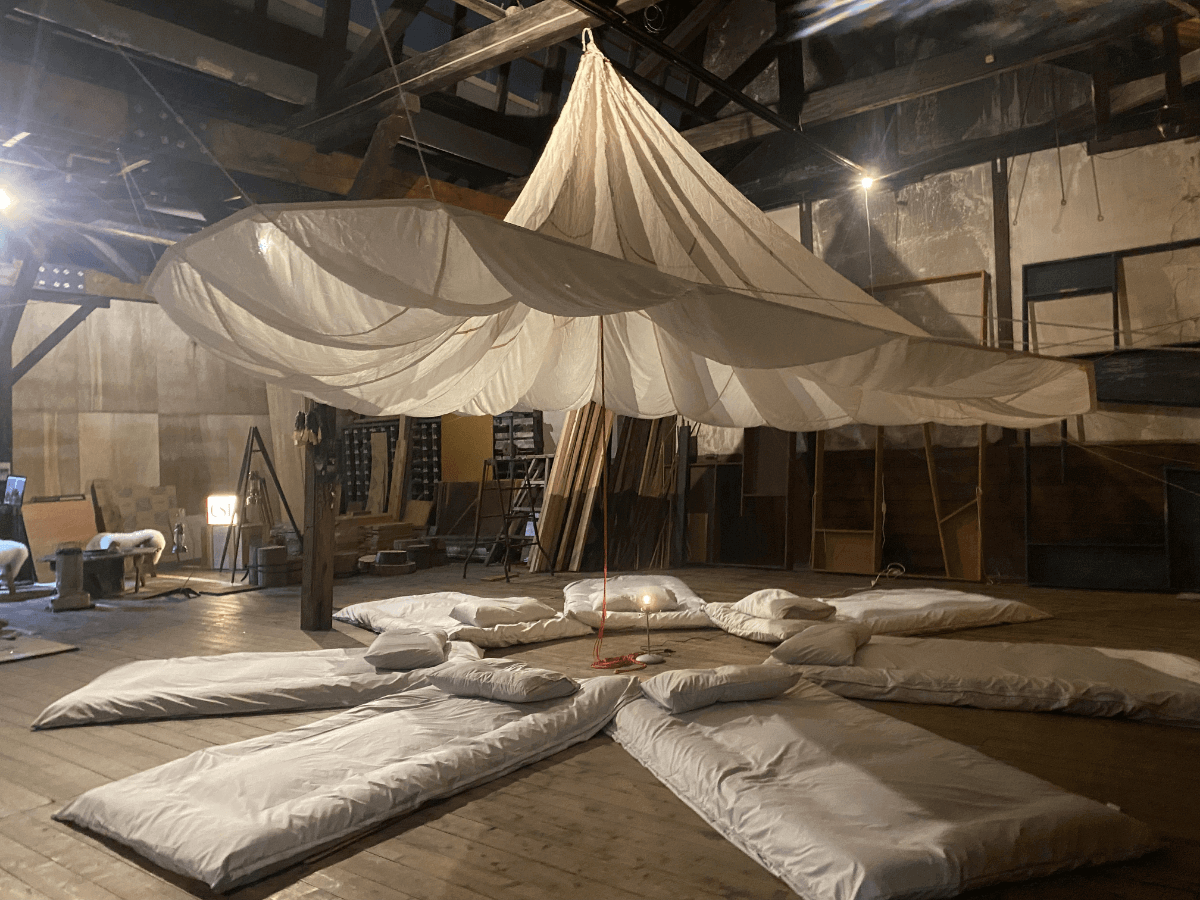

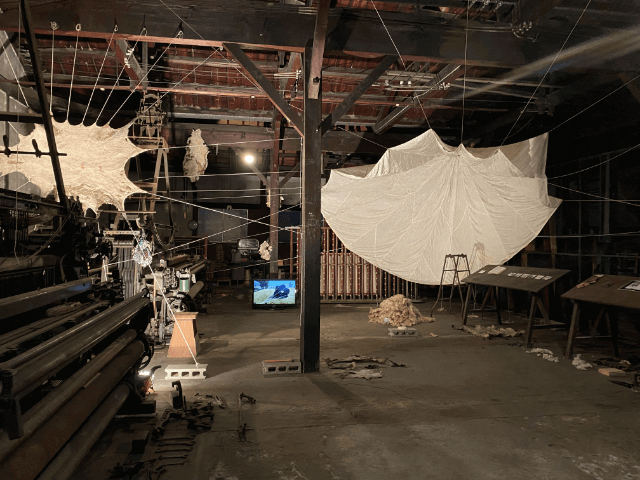

On display at the exhibition is an Imperial Japanese Army silk parachute (made in 1944) sewn by female workers at an airfield in Kyushu, Japan.

Other exhibits include items related to the Tomioka Silk Mill in Gunma Prefecture; silk thread produced at the Usui Raw Silk Factory, which is still in operation using machinery from that time; old silk from the former Tokyo Muslin Silk Mill, where “Joko Aishi (the tragic history of the women textile workers)” is set; ceramic hand grenades collected from all over Japan; and various documents and other materials related to female factory workers.