Here is a book.

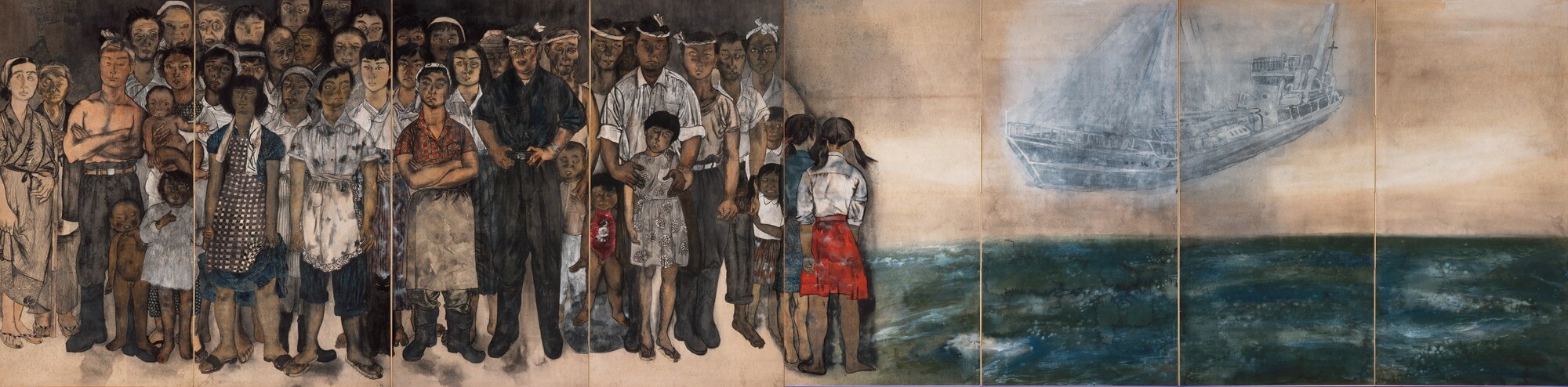

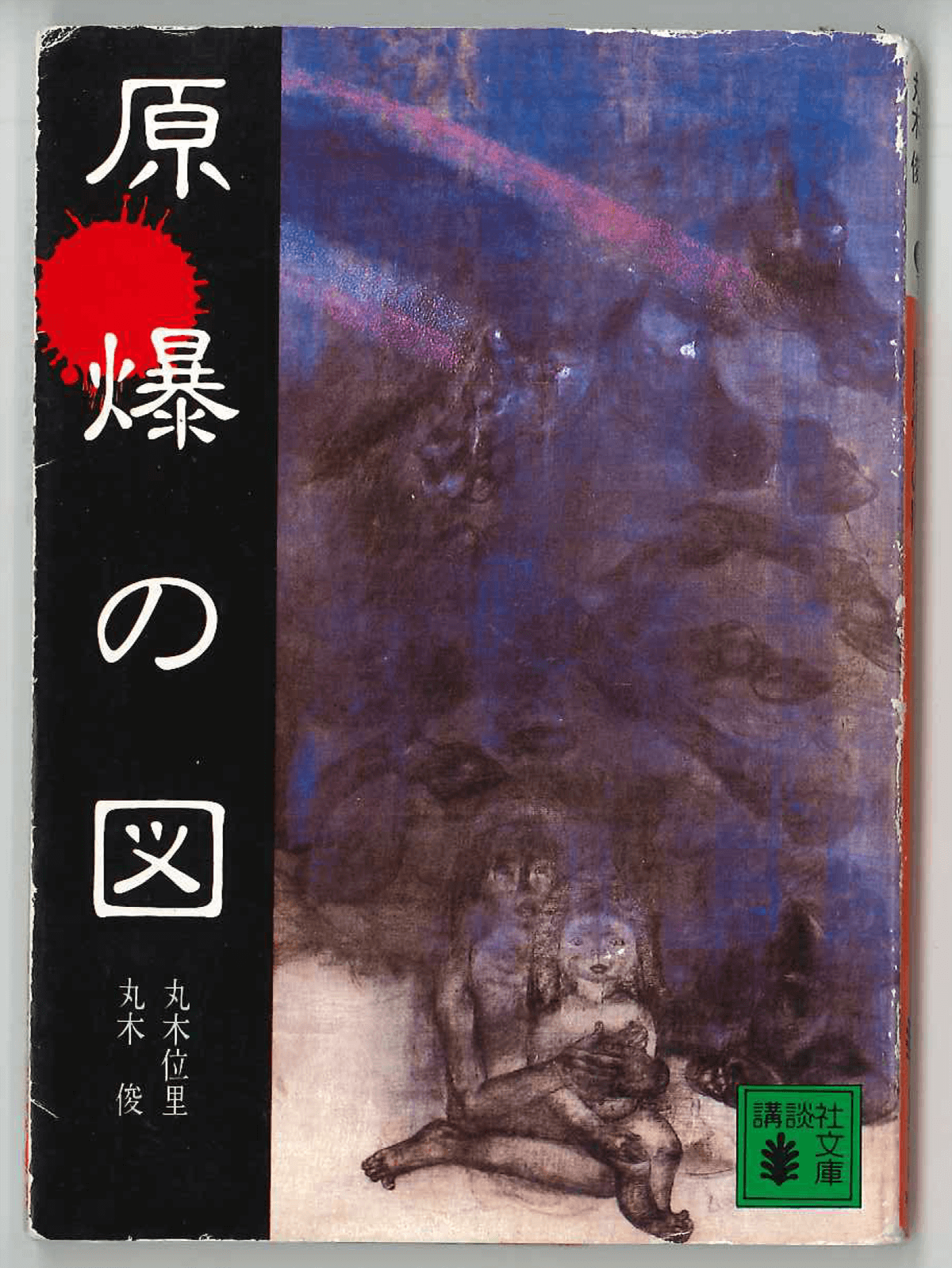

A small art book, The Hiroshima Panels was published in 1980.

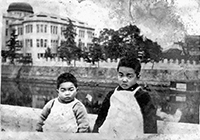

Why did Maruki Toshi and Maruki Iri spend more than 30 years creating 15 paintings for the panels? The thoughts and driving forces that keep them painting are described in their own words. In the afterword of the book, the following is written:

For more than 30 years, we have been painting with the prayer, “Please stop the atomic bombs, please stop the war.” However, the number of atomic bombs has not decreased, but only increased. Many countries now have atomic bombs. Every day we hear the words “big ones, small ones, nuclear warheads, missiles, nuclear submarines,” and so on. We do not know when another war will break out. What should we do? How can we cope with the spread of atomic bombs that will soon be used to injure and kill more people? What should we do?

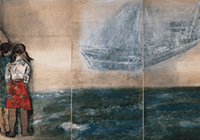

Iri and Toshi had intended to continue painting “The Hiroshima Panels,” rather than ending with the 15th part.

More than 70 years have passed since The Hiroshima Panels were published. More and more countries are building up their nuclear arsenals, and it is said that this is the “Third Nuclear Age.” In this modern age “The Hiroshima Panels” has taken on a new meaning and has become a significant and resonant presence.

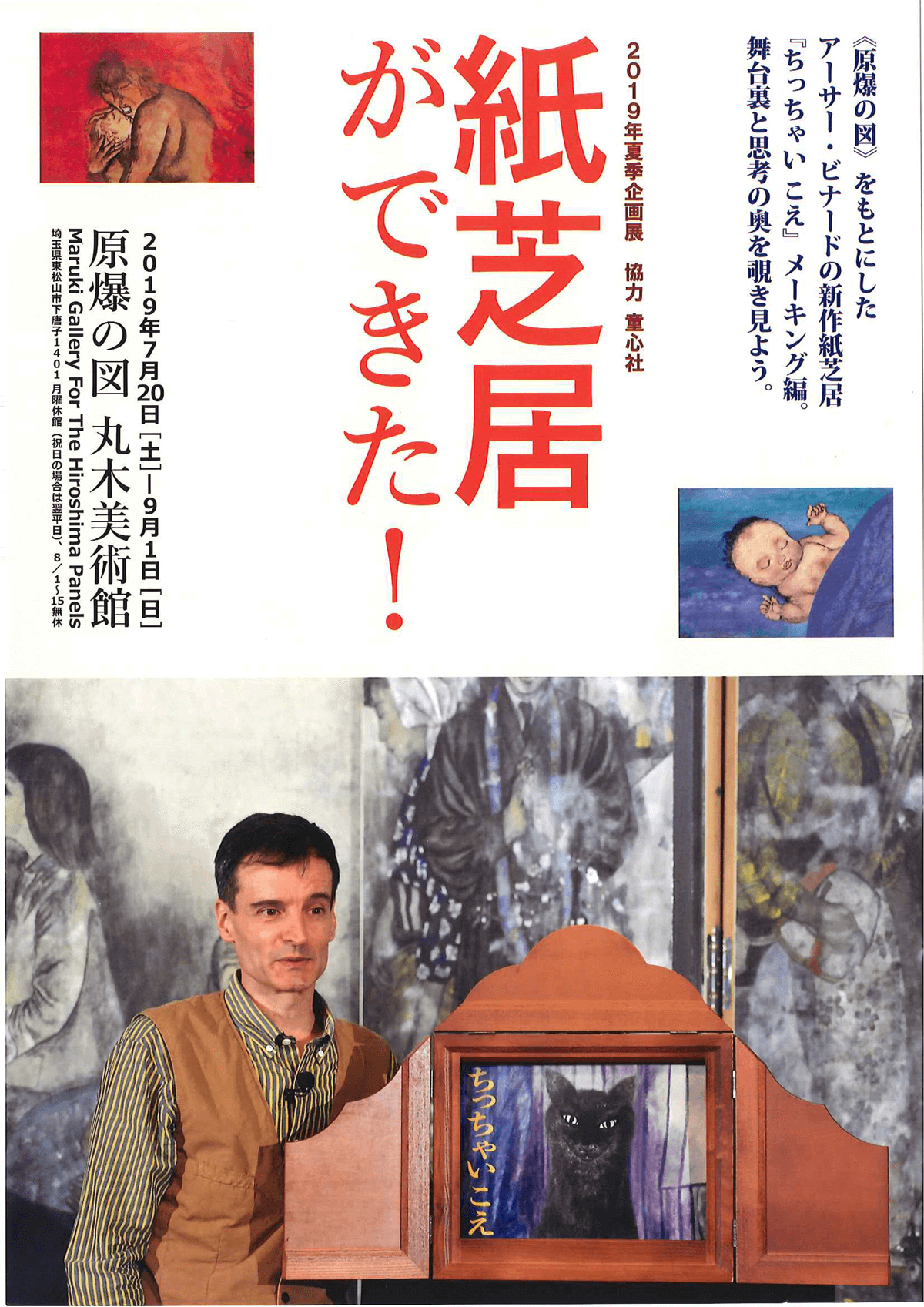

Rather than letting their awareness of the issues be a thing of the past, we must consider the significance of the Panels and pass it on to the future. The exhibition was designed to help those of us living today think about “Why do wars begin?” What should we do about the nuclear problems we face today?”

The exhibition will be held in cooperation with the Maruki Gallery.