Hidden (Unknown) Story Told by Mother Britt

To Japan

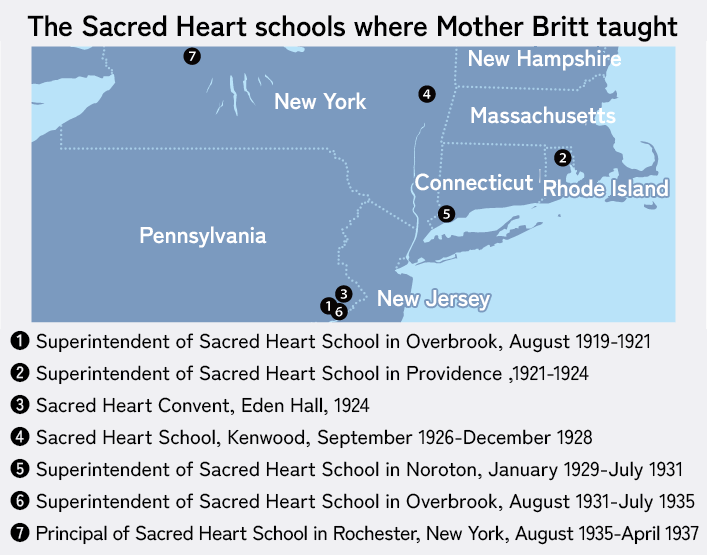

In the year 1937, at the age of thirty-nine, I was called to embark on a journey to Japan. As a member of the Society of the Sacred Heart, *1 I traveled from the United States to work at Sacred Heart School in Tokyo. My assignment was clear: to teach and serve in this distant land, where the ideals of our Foundress, St. Madeleine Sophie Barat, could take root and flourish. Sacred Heart’s educational principles were not foreign to me—they had been my guiding principles for nearly two decades of service in the United States. The focus was always the same: to educate young minds with intellectual rigor and the creativity to serve society, honoring each individual’s unique potential.

War, Internment, and the Return to the U.S.

As the world plunged into the turmoil of the Pacific War, my life, too, took an unexpected turn. On December 8, 1941, as I had only just begun to settle into my life in Japan, the war erupted. We, the members of the Sacred Heart community, continued to teach amidst rising tensions, but the storm of conflict soon reached our doorstep. On September 16, 1942, I was one of twenty-seven Sacred Heart nuns with Allied nationalities who were arrested and sent to an internment camp in Ota Ward.*2

The experience was harsh, but the Sacred Heart spirit was alive and well. *3 I was inspired to learn that the graduates of Sacred Heart took up the mantle of teaching, ensuring that the school’s mission would not be interrupted.

In 1943, after several long months of wartime hardships, I was given temporary leave to return to the United States. The journey itself was a test of endurance, as we traveled aboard the Teia-Maru, a ship designed for 450 passengers, but carrying far more. Along the way, we stopped in Shanghai, the Philippines, Saigon, and Singapore before transferring to the Swedish-American Gripsholm Liner in Goa, India.

After nearly three months at sea, on December 1, 1943, we finally arrived in New York.*4 My heart swelled with relief as I was reunited with Reverend Mother and two nuns at the Kenwood Sacred Heart Convent. The warmth of that embrace, after all the uncertainty and fear, remains a cherished memory.

Social Service at Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart

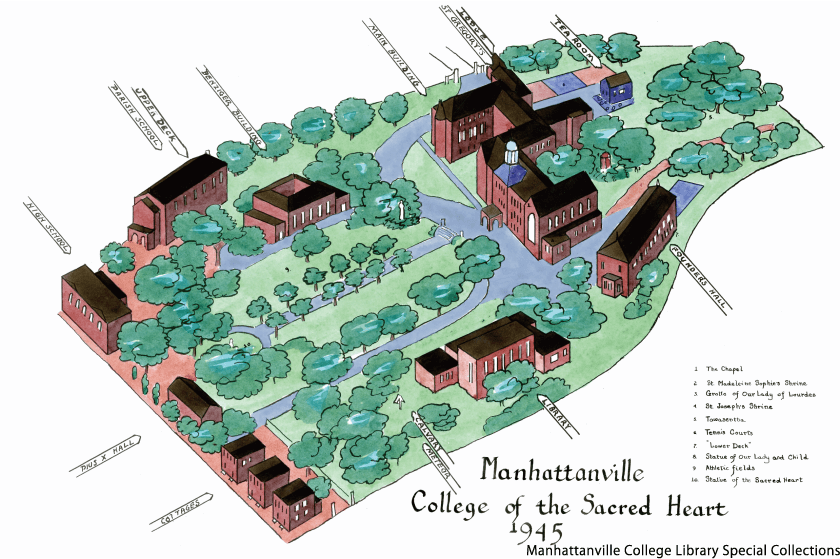

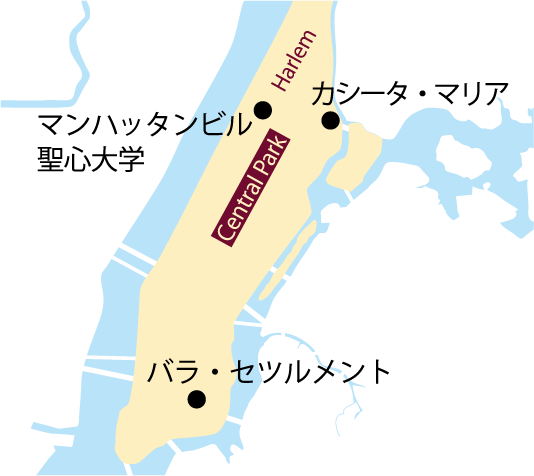

Upon my return to the United States, I was asked to teach for the first time at the university level, at Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart. I was entrusted with a class of third-year students. I saw the same passion for service and social justice that had been instilled in me over the years. Under the leadership of Mother Dammann, the president, *5 Manhattanville became a hub for human rights, racial equality, and social justice—values that resonated deeply within me.

The students’ involvement in social service activities was a true testament to the ideals of Sacred Heart education. Whether it was organizing picnics for underprivileged children or collecting food, clothes, and toys for victims of natural disasters, the students of Manhattanville embodied the mission of the Sacred Heart in ways that were both practical and deeply meaningful.

A Return to Japan

In September 1946, after the end of the war, I returned to Japan on the first ship allowed after the war. I met Mrs. Elizabeth Vining, who would later become the English tutor for Crown Prince Akihito. We shared stories of our work, unaware that, in the coming years, we would watch as the crown prince became Emperor, while my own role would be forever altered.*6

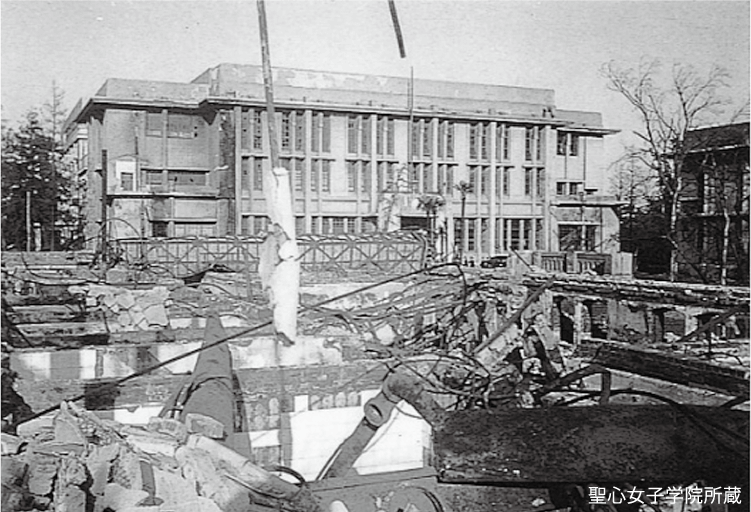

The moment I set foot in Tokyo again, I was met with a scene that broke my heart. The Sacred Heart campus, which had once been a thriving center of education and spiritual life, was reduced to rubble, destroyed in the Great Tokyo Air Raid. But amid the devastation, the smiles of my fellow Sisters welcomed me back, and I knew I had a duty to rebuild, not just the physical structures, but the spirit of Sacred Heart education itself.*7

As I took on the role of Vice Principal at the International Sacred Heart School in Tokyo, I was also tasked with preparing for the establishment of the University of the Sacred Heart.

Birth of the University of the Sacred Heart

By 1948, I found myself appointed as the first president of the University of the Sacred Heart. I drew inspiration from my time at Manhattanville—academic rigor, leadership through student government, and a strong emphasis on social service. I knew we had to prepare these young women to be leaders who would act thoughtfully, always considering the needs of others.

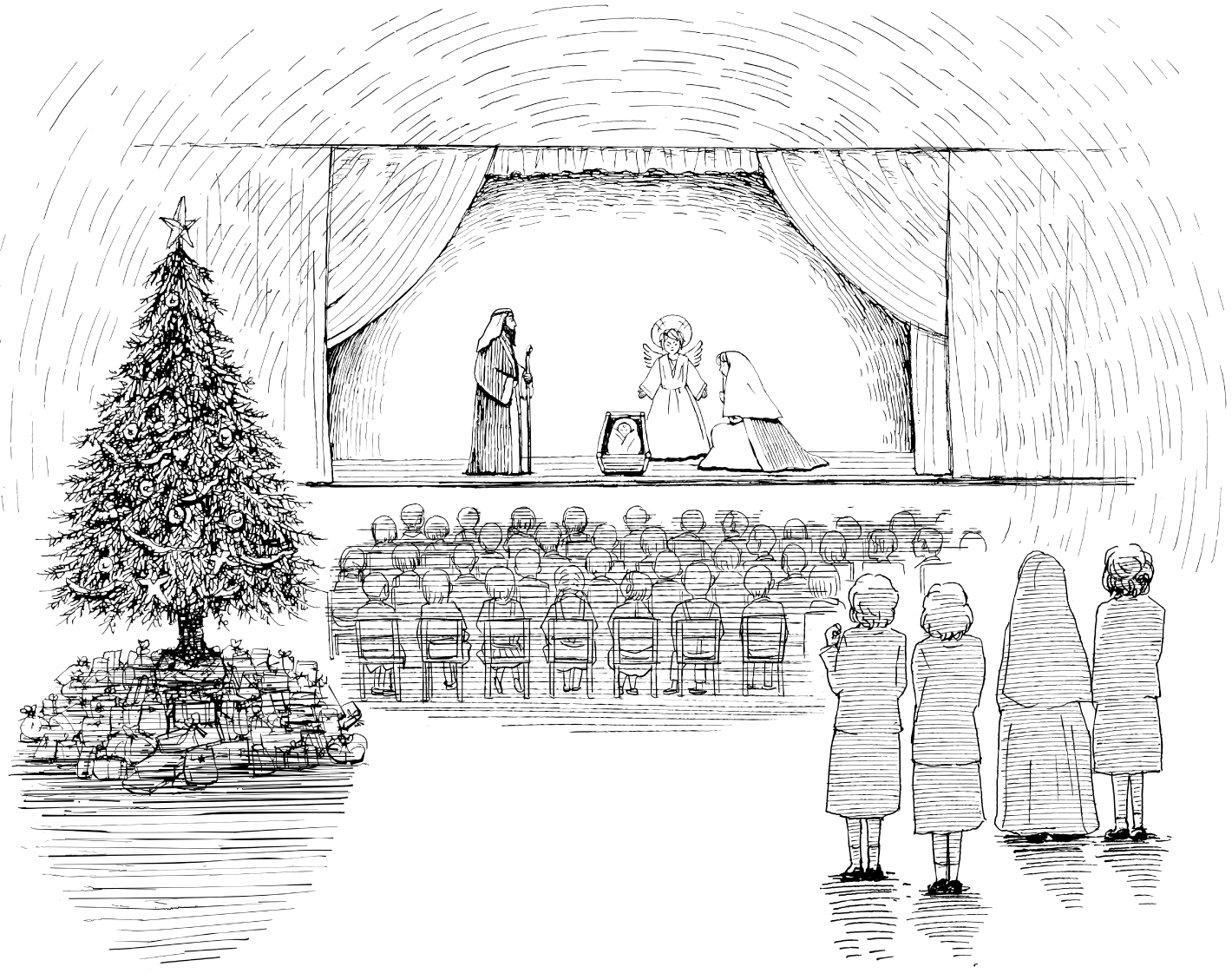

I drew inspiration from my time at Manhattanville College, where the students’ service to their communities had left an indelible mark on me. We began with a Sunday school for children in the nearby neighborhood, and soon, our students were organizing Christmas plays, providing gifts, and offering their time and talents to those in need.

A Legacy of Service and Leadership

As the University of the Sacred Heart grew, so did our commitment to social outreach. From collecting relief supplies for those in need, to organizing summer camps and seaside retreats for underprivileged children, the students of our university were quick to take up the call to serve.

University of the Sacred Heart Yearbook 1952

University of the Sacred Heart Yearbook 1964

University of the Sacred Heart Yearbook 1964

I thought of Mother Hermanna Mayer *8 at Obayashi Sacred Heart in Takarazuka. She had been such a visionary, founding the Sacred Heart Settlement, where students could work with underprivileged children. I admired her greatly—she was my mentor.

Obayashi Sacred Heart School

Obayashi Sacred Heart School

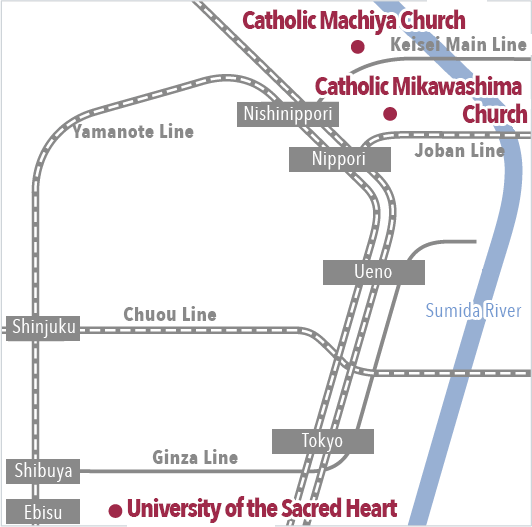

Mikawashima Settlement

One of the meaningful endeavors was our partnership with the Mikawashima Settlement, *9 where students volunteered every weekend to tutor children and engage in play. These young women were not simply students—they were mentors, role models, and leaders in their own right. The annual events at the University, where we invited about 200 children from Mikawashima to spend the day on campus, became cherished traditions, further cementing our commitment to fostering both academic and social growth.

University of the Sacred Heart archive

University of the Sacred Heart Yearbook 1963

University of the Sacred Heart Yearbook 1952

University of the Sacred Heart archive

University of the Sacred Heart Yearbook 1952

University of the Sacred Heart Yearbook 1963

- *1

- The Society of the Sacred Heart was founded in Amiens, France in 1800 by Madeleine Sophie Barat, shortly after the French Revolution, and the Sacred Heart School opened in Paris the following year. Since then, many sister schools have developed in countries and regions around the world.

In 1908, Salmon and four other members of the Society of the Sacred Heart were sent from Australia to Japan, and in 1910, Sacred Heart School, Tokyo, high school, elementary school, kindergarten and language school “Gogakko” (foreign department) were opened in Tokyo.

In 1818, Philippine Duchesne and five other members of the Society of the Sacred Heart were sent from France to the United States, and the Academy of the Sacred Heart opened in St. Charles, Missouri in the same year.

- *2

- The 27 Sacred Heart members interned at the Tokyo Internment Camp (now Denenchofu Futaba Gakuen), nicknamed “Violet,” had three Irish, five American, three English, eight Australian, one Canadian, one New Zealander, and six Maltese nationalities. The 140 women’s internment camp (all except six were nuns) under the jurisdiction of the Tokyo Police Department suffered “cramped lives, with small shared rooms, meager meals, and a rigid daily schedule,” but despite the inconvenience, they managed to find ways to cope with the situation, such as holding language study sessions and reading groups using books sent from neutral countries. Mother Britt also gave lectures on philosophy (according to a letter from interned members).

- *3

- The Sacred Heart (Seishin) Spirit

At the heart of the Sacred Heart education is the Seishin Spirit - a way of living that reflects our deepest values. It means being sensitively attentive and responsive to the needs of others, and using ones mind, heart, hands and willingness to take actions to make a positive difference in the world around us.

- *4

- During the 79-day voyage from the departure from Yokohama Port on September 14, 1943 to the arrival in New York Harbor on December 1st, one of the passengers, George Wilder (missionary and ornithologist), recorded on a map (see QR code and URL below) the points they passed at noon everyday, the dates, and the dates of port calls and arrivals. The map also shows that they crossed the equator four times.

https://www.salship.se/mercy.php

https://www.salship.se/mercy.php

After leaving Yokohama Port, the Teia Maru called at Osaka, Shanghai, Hong Kong, San Fernando (Philippines), Saigon, and Shonan Island (Singapore), before arriving at Goa, a Portuguese colony in India, on October 15th. Passengers bound for America transferred to Gripsholm, which departed on the 21st, calling at Port Elizabeth in the Union of South Africa and Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, before arriving in New York Harbor on December 1st.

(Reference material)

Wilder, George. “Birds Seen from the Decks of the Exchange Ships, Teia Maru and Gripsholm, September 20 to December 1, 1943” in 5. REPATRIATION Voyage(September 20 to December 1), N.d., n.p.,pp.163-199.

Shunsuke Tsurumi, Norihiro Kato, So Kurokawa Japan-US Exchange Ship, Shincho-sha 2006

(Confirmed on 10.7 2023)

This site is about the voyage of the Drottningholm and Gripsholm, which were used as exchange and repatriation ships during World War II. Created by Lars Hemingstam, the site will be updated and revised as more information is collected. For the voyage of the Gripsholm, an exchange ship from Japan to the United States in 1943, scroll down (more than halfway down) to see maps and other materials by George Wilder.

- *5

-

President Mother Dammann strongly advocated for the protection of human rights, the elimination of racial discrimination, and social justice, and accepted African-Americans despite strong opposition from some graduates. Her paper, “Principles Versus Prejudices,” was presented at the alumni meeting on May 31, 1938, and was subsequently widely read among administrators at other universities. President Dammann`s respect for diversity and firm belief in inclusiveness have had a major impact on other universities, and remain a characteristic of the education of Manhattanville College to this day.

Manhattanville College of the Sacred Heart was detached from the management of the Society of the Sacred Heart in 1999 and became Manhattanville University.

https://www.mville.edu/about/index.php

(Confirmed on 10.2, 2023)

Website of University of Manhattanville. From page 2 onward, the following characteristics of the educational policy are described: “To develop leaders who have a sense of responsibility to value diversity, fairness and social justice and do not exclude anyone to serve in a global community. “

“To educate ethical and socially responsible leaders in a global community.” (From Website)

- *6

- For a reference on the episode of her meeting Mrs. Vining on board a ship during Mother Britt return to Japan in 1946 after the war, see Elizabeth G. Vining. Return to Japan. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Co., 1960. A related reference is Elizabeth G. Vining`s “The Crown Prince’s Window” (translated by Ichiro Koizumi, Bungei Shunju, 1953).

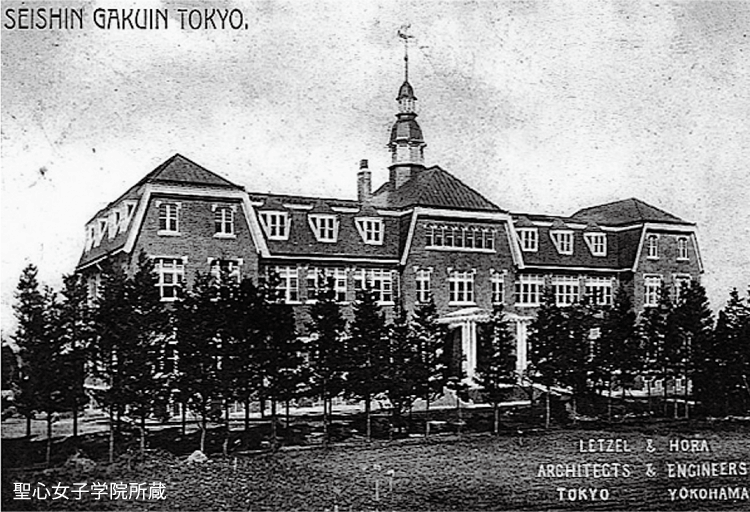

- *7

- Sacred Heart School was located in the main building in the center of this building. After being partially destroyed in the Great Kanto Earthquake, it was restored, but was burned down in the Great Tokyo Air Raid on March 10, 1945. The main gate of this building was designed by Czech architect Jan Letzel, who is also known as the designer of the Atomic Bomb Dome in Hiroshima. The main gate is still used as the main gate of Sacred Heart School Tokyo today.

- *8

-

Mother Mayer invited members of the Aitoku Shimai Kai*, a religious order involved in social welfare work, from France to Osaka, and they established the Sacred Heart Settlement (a nursery Schoo., sanatorium, etc.) to provide relief to people in an area of city of Osaka where many people lived in poverty. In response to requests from the local community, they also established a free nursery school, The Barat Home, right next to Obayashi Sacred Heart School.

* Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul (English name) Filles de la charité de Saint Vincent de Paul (French name)

While supporting the management of these facilities with the profits from bazaars and charity concerts, as well as donations from collaborators, she guided the students’ community service activities to support growth of children in good health with enthusiasm. Every year, more than 100 children from Sacred Heart Settlement were invited to Obayashi Sacred Heart campus for a picnic day to spend time with the students, which had become a tradition. Some university students would run to the Barat Home, located just a few minutes from the school, during breaks in between classes to look after the children.

Mother Britt saw Mother Mayer′s passion for social service in the actions of her students and later said, “I learned this spirit from Mother Mayer, whom I admired the most . . . Mother established Barat Home at the foot of the hill (mountain?) in Obayashi, invited the Sisters from Aitoku Kai, and had the student∂∂s to help there. In this way, I was able to help many people, and I also taught the students to develop a sense of responsibility toward society for their future.”

- H. Cieslik, Meeting a Great Educator: Memories of Mother Britt, in A Memorial Tribute to Mother Britt, in A Memorial Tribute to Mother Britt, compiled by the Sacred Heart University Alumnae Association, 1969, p. 36.

- *9

-

The Sophia (Jyochi) Settlement was established in 1923 as an organization and initiative aimed at improving the lives of residents in a poverty-stricken area of Mikawa Town, Tokyo Prefecture (present-day Arakawa Ward, Tokyo). Father Hugo Lassalle, a professor at Sophia University, along with two students, moved into the community to live among the residents. By interacting with them in their daily lives, they provided support in areas such as childcare, education, and healthcare. The initiative also aimed to raise students′ awareness of and interest in social work. (See Sophia Catholic Settlement No. 30 for reference.) For more details and photographs of the activities, please refer to the information below.

The original meaning of the word “settlement” was the activity and facilities for the purpose of volunteers such as intellectuals, religious leaders, and students settling in areas like slums to improve their lives by interacting with residents and children on a daily basis. It began in the UK and the U.S. in the early 1900s. In the U.S., many of these were aimed at immigrants in particular.

(References)

NPO Mize Welfare Fund, “Sophia University Settlement 1930-1967,” 2017.

Sophia Catholic Settlement Alumni Association, “The Footprints of Sophia University Settlement - Notes from Settlers and Their Companions,” 2015.

For details on the organization of Sophia Settlement, see the “Sophia / Jyochi Catholic Settlement Directory,” n.p. 1935.