A small town about 60 kilometers north of Prague and located close to Auschwitz, Terezín, was was later called “the antechamber of hell,” and as many as 144,000 Jews were sent there, 15,000 of whom were children. Separated from their families, children suffered hunger, cold, violence, and fear. One of the surviving children looked back to Ms. Friedl Dicker’s art classes as their “only one good memory.” What “feelings” are conveyed in the drawings left behind? We will think about children’s “lust for life” with Ms. Michiko Nomura, who continues her activities to pass on the existence of the children’s drawings and the Holocaust to the next generation.

Exhibition 2

Drawings left behind by the children in the Terezín Ghetto

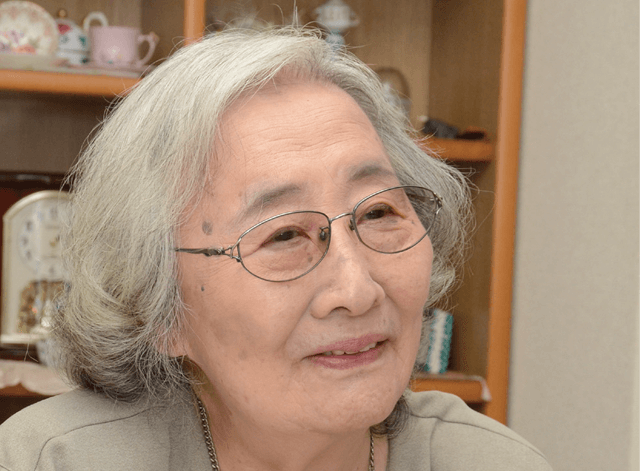

Michiko Nomura

(Nonfiction writer)

[Profile]

Born in Tokyo in 1937, graduating from Waseda University in 1959 with a degree in French literature from the Department of Literature. After working as a copywriter and editor-in-chief of a town magazine, she wrote essays and reportage for newspapers and magazines. In 1989, she encountered pictures of the children of Terezín in Prague and negotiated with the Embassy of the Czech Republic, the Jewish Museum, and others to publicize the fact and obtained permanent rights to use 150 replicas of the drawings.

Since 1991, she has held the “Terejin-shuyojo no Osanai Gaka-tachi ten (Young Painters of the Terezín Ghetto exhibitions)” at 23 venues in Japan.

She has continued to interview the few survivors, hold exhibitions, write books, and give lectures for 32 years. In order to convey the facts of the Holocaust, she also organizes tours to Poland and the Czech Republic, and tours to Tsuruga City, Yaotsu Town, Fukuyama City, and other cities in Japan.

She won the Grand Prize of the Sankei Children's Book Award for her book, Terejin no Chiisana Gaka-tachi (Little Painters of Terezín) and she has also written many books, including Furiidoru sensei to Terejin no Kodomo-tach (Friedle and the Children in Terezín) and Seikansha-tachi no Koe o Kiite (Listening to the Voices of Survivors).

Since 2010, Friidoru to Terejin no Chiisana Gaka-tachi (Friedl and Young Painters in the Terezín) has been included in a 6th grade Japanese language textbook for elementary school students (Gakkotosho). She had given many lectures at elementary and junior high schools, where students are learning from that textbook.

She has performed “Terejin mo Chocho ha inai (Terezín, No More Butterflies),” a concert of readings and songs, composed mainly from poems left behind by the children in Terezín, throughout the country, and in 2001 in Prague and Terezín.

In March 2023, she will resume a tour to Israel, one of her long-standing trips to learn about the Holocaust, and she continues her efforts to convey the message.

The “Life, Peace, and Encounter: Lecture and Concert ‘Terezín, No More Butterflies’” can be viewed here.

Born in Tokyo in 1937, graduating from Waseda University in 1959 with a degree in French literature from the Department of Literature. After working as a copywriter and editor-in-chief of a town magazine, she wrote essays and reportage for newspapers and magazines. In 1989, she encountered pictures of the children of Terezín in Prague and negotiated with the Embassy of the Czech Republic, the Jewish Museum, and others to publicize the fact and obtained permanent rights to use 150 replicas of the drawings.

Since 1991, she has held the “Terejin-shuyojo no Osanai Gaka-tachi ten (Young Painters of the Terezín Ghetto exhibitions)” at 23 venues in Japan.

She has continued to interview the few survivors, hold exhibitions, write books, and give lectures for 32 years. In order to convey the facts of the Holocaust, she also organizes tours to Poland and the Czech Republic, and tours to Tsuruga City, Yaotsu Town, Fukuyama City, and other cities in Japan.

She won the Grand Prize of the Sankei Children's Book Award for her book, Terejin no Chiisana Gaka-tachi (Little Painters of Terezín) and she has also written many books, including Furiidoru sensei to Terejin no Kodomo-tach (Friedle and the Children in Terezín) and Seikansha-tachi no Koe o Kiite (Listening to the Voices of Survivors).

Since 2010, Friidoru to Terejin no Chiisana Gaka-tachi (Friedl and Young Painters in the Terezín) has been included in a 6th grade Japanese language textbook for elementary school students (Gakkotosho). She had given many lectures at elementary and junior high schools, where students are learning from that textbook.

She has performed “Terejin mo Chocho ha inai (Terezín, No More Butterflies),” a concert of readings and songs, composed mainly from poems left behind by the children in Terezín, throughout the country, and in 2001 in Prague and Terezín.

In March 2023, she will resume a tour to Israel, one of her long-standing trips to learn about the Holocaust, and she continues her efforts to convey the message.

The “Life, Peace, and Encounter: Lecture and Concert ‘Terezín, No More Butterflies’” can be viewed here.

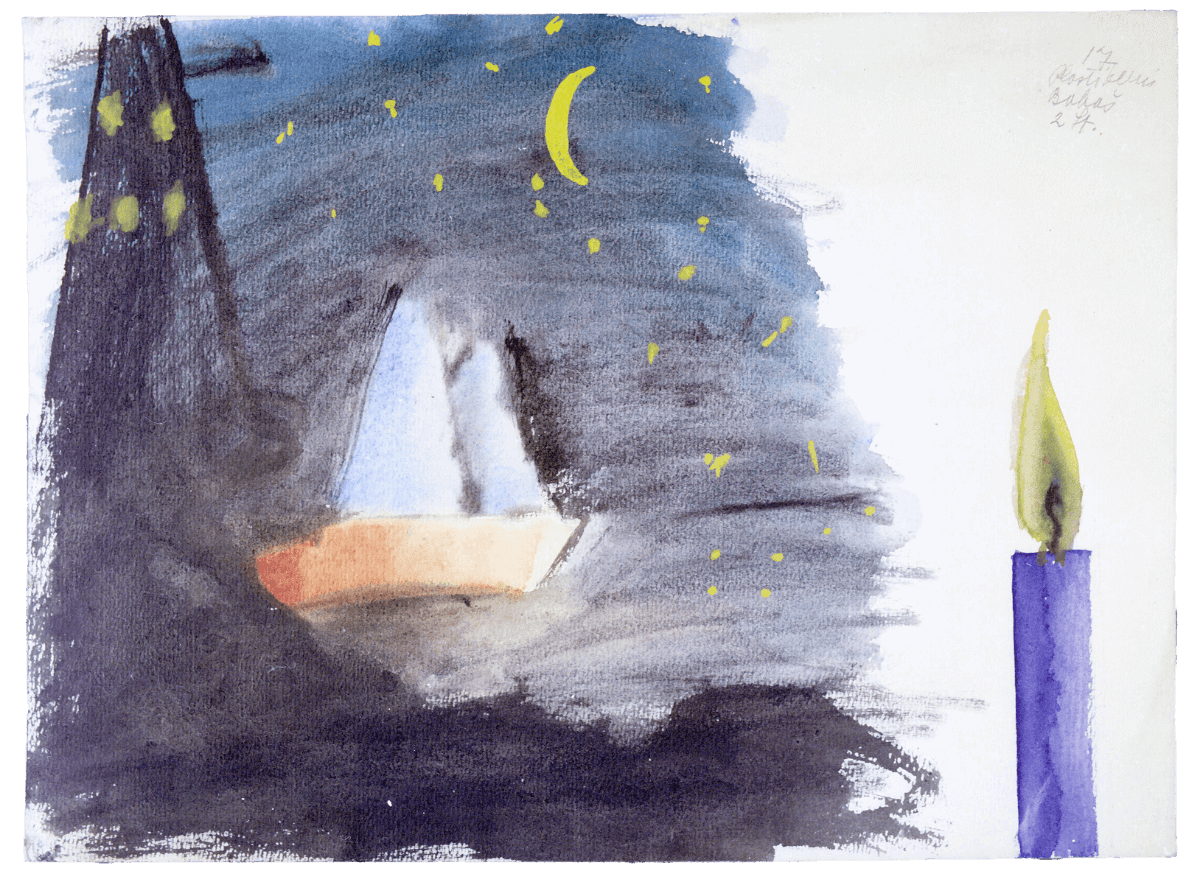

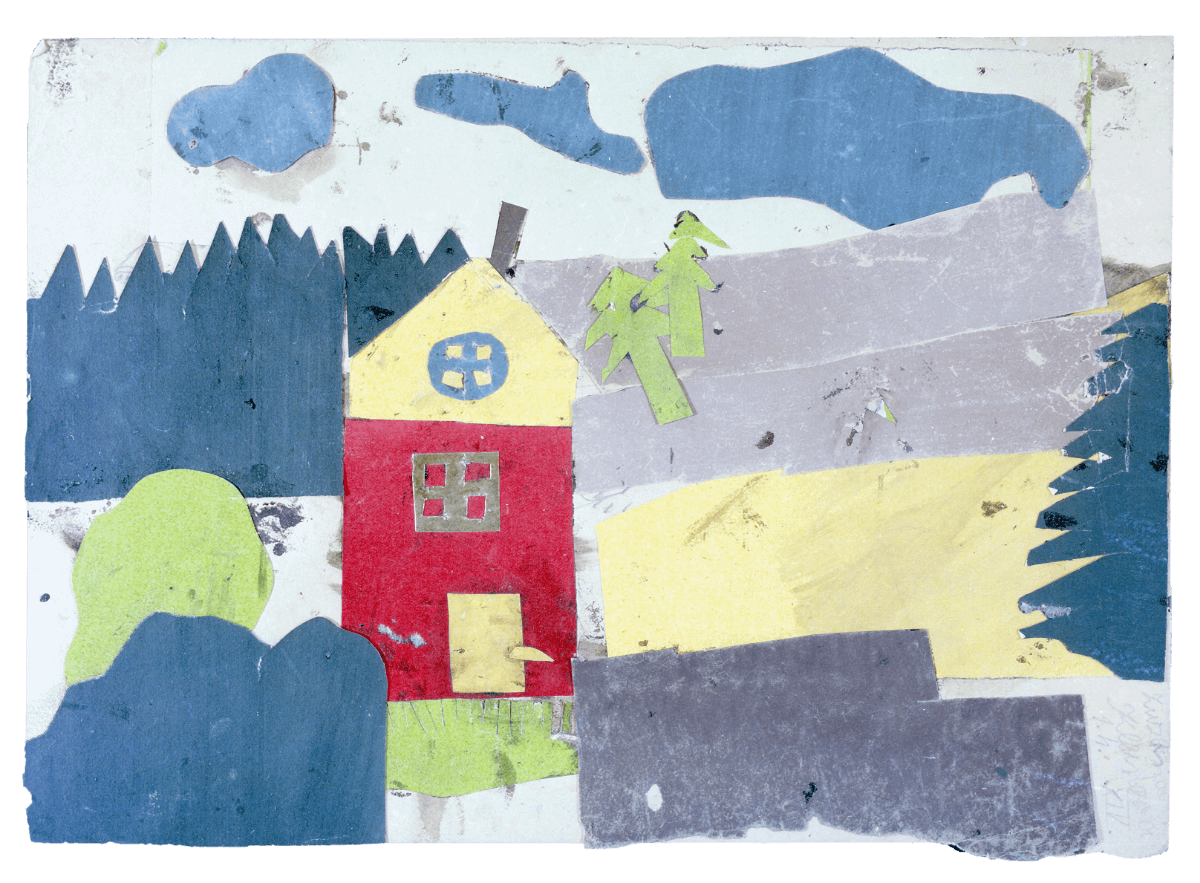

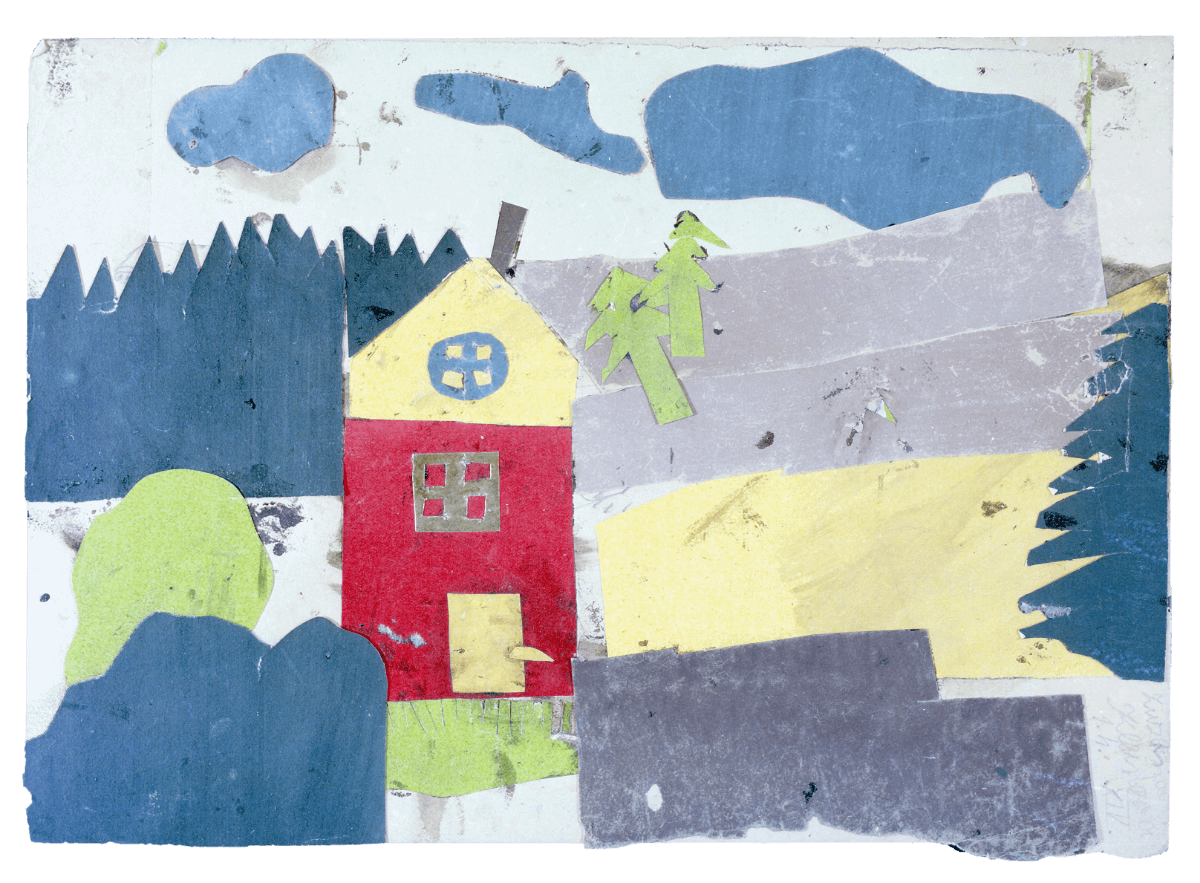

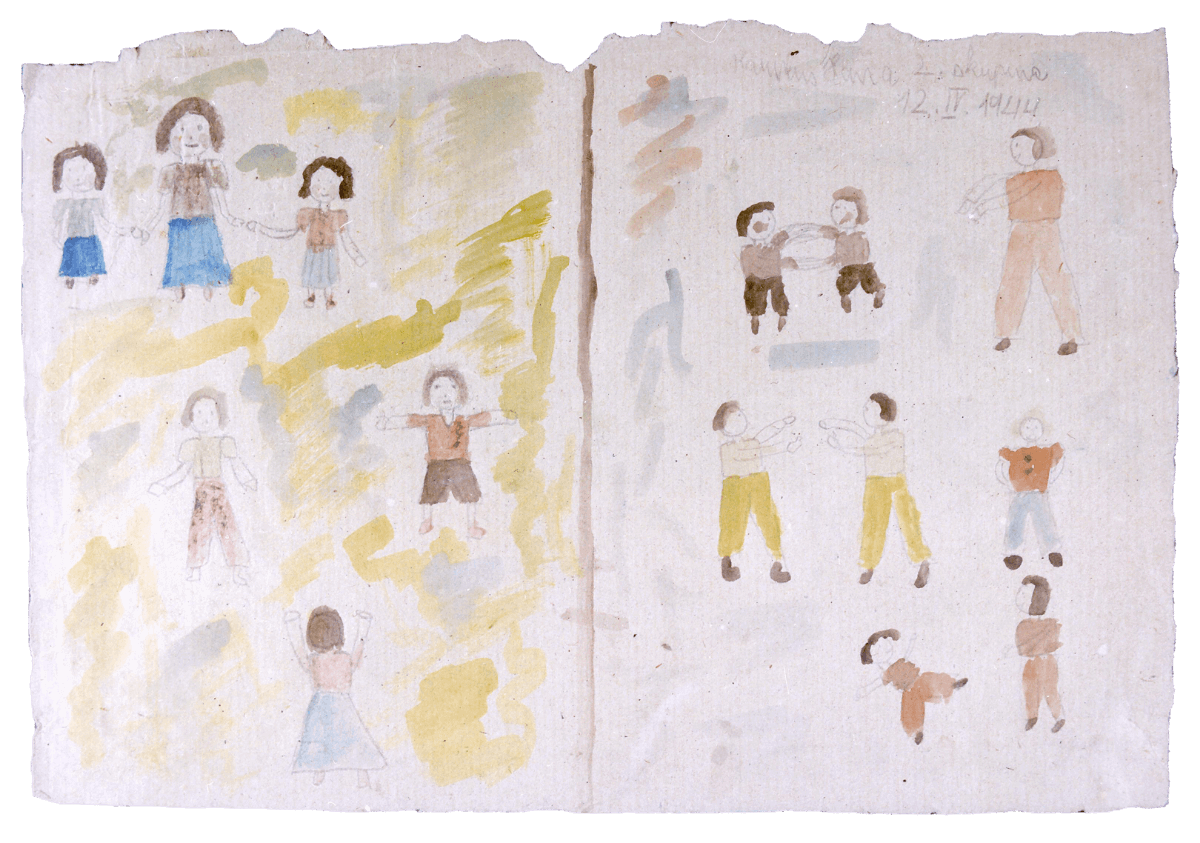

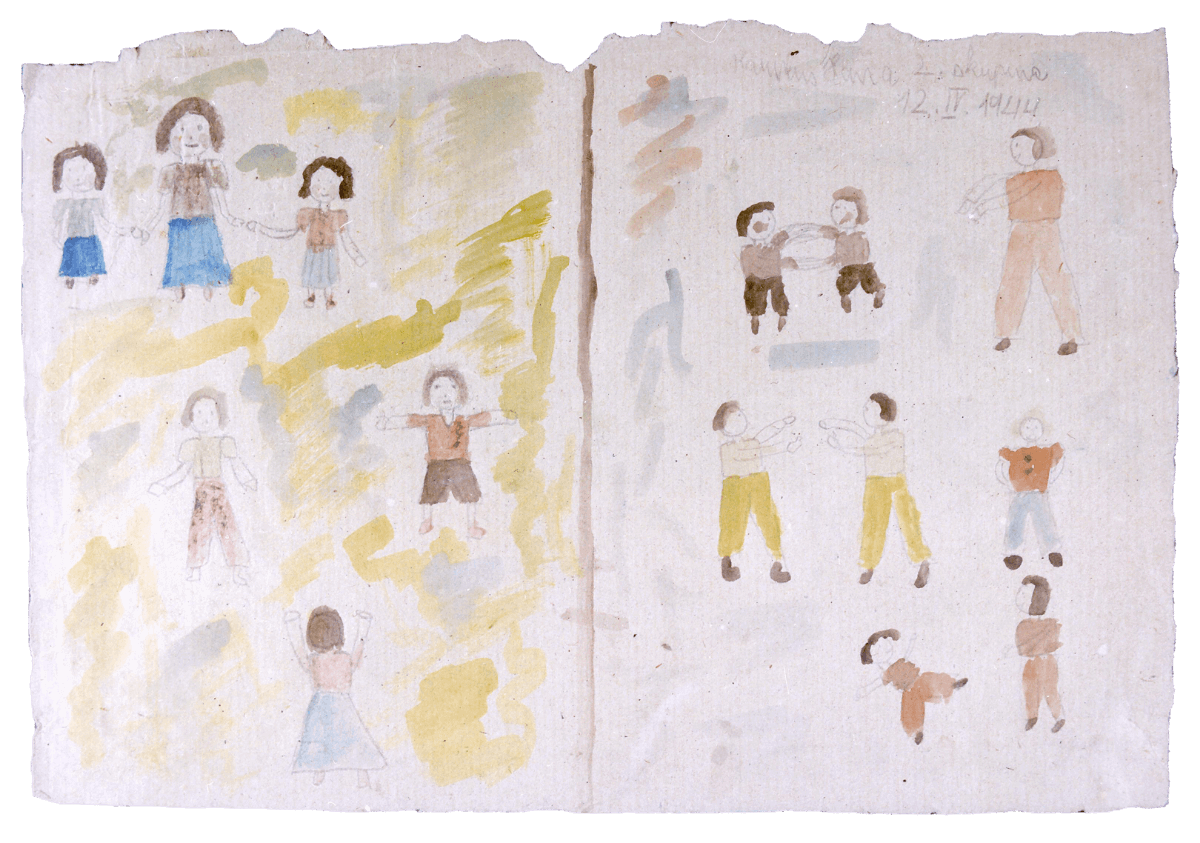

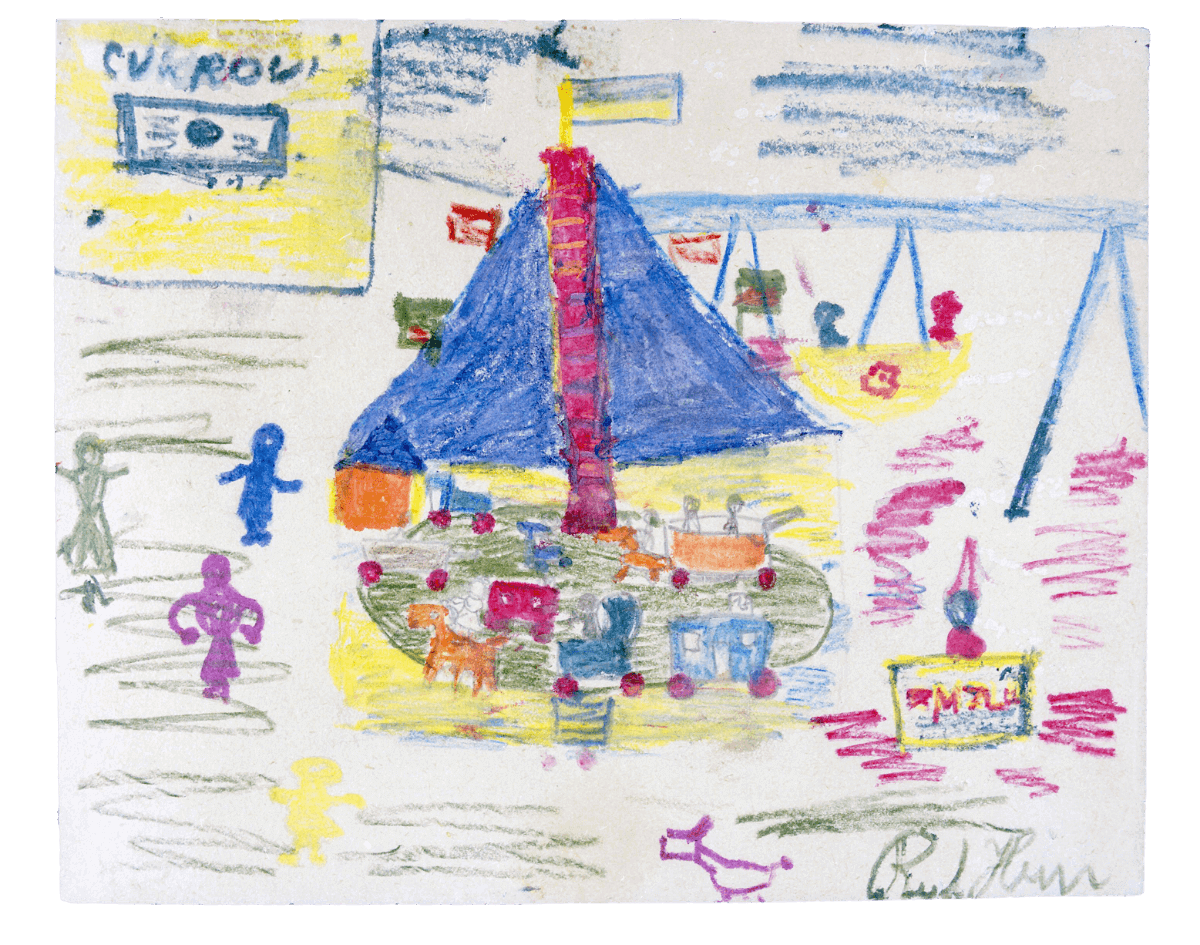

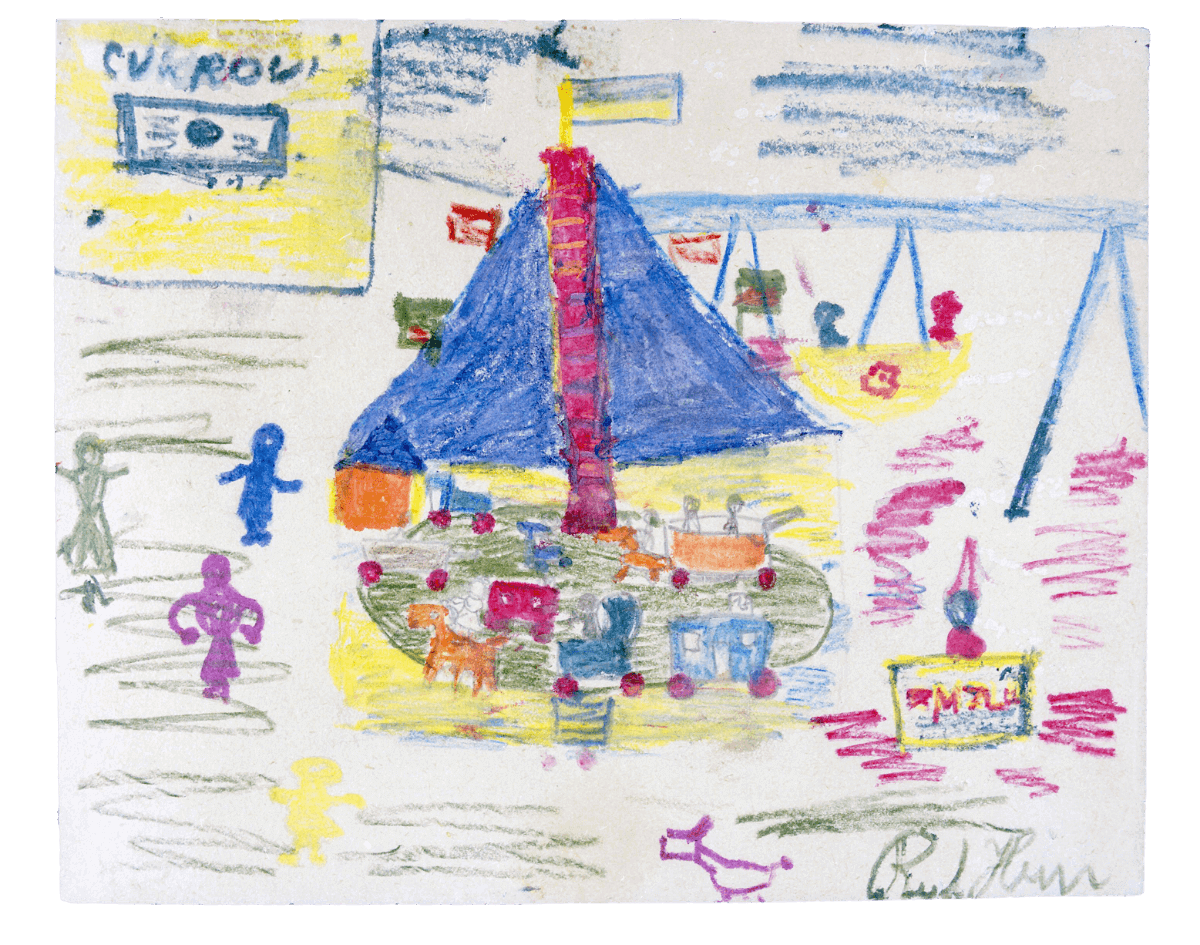

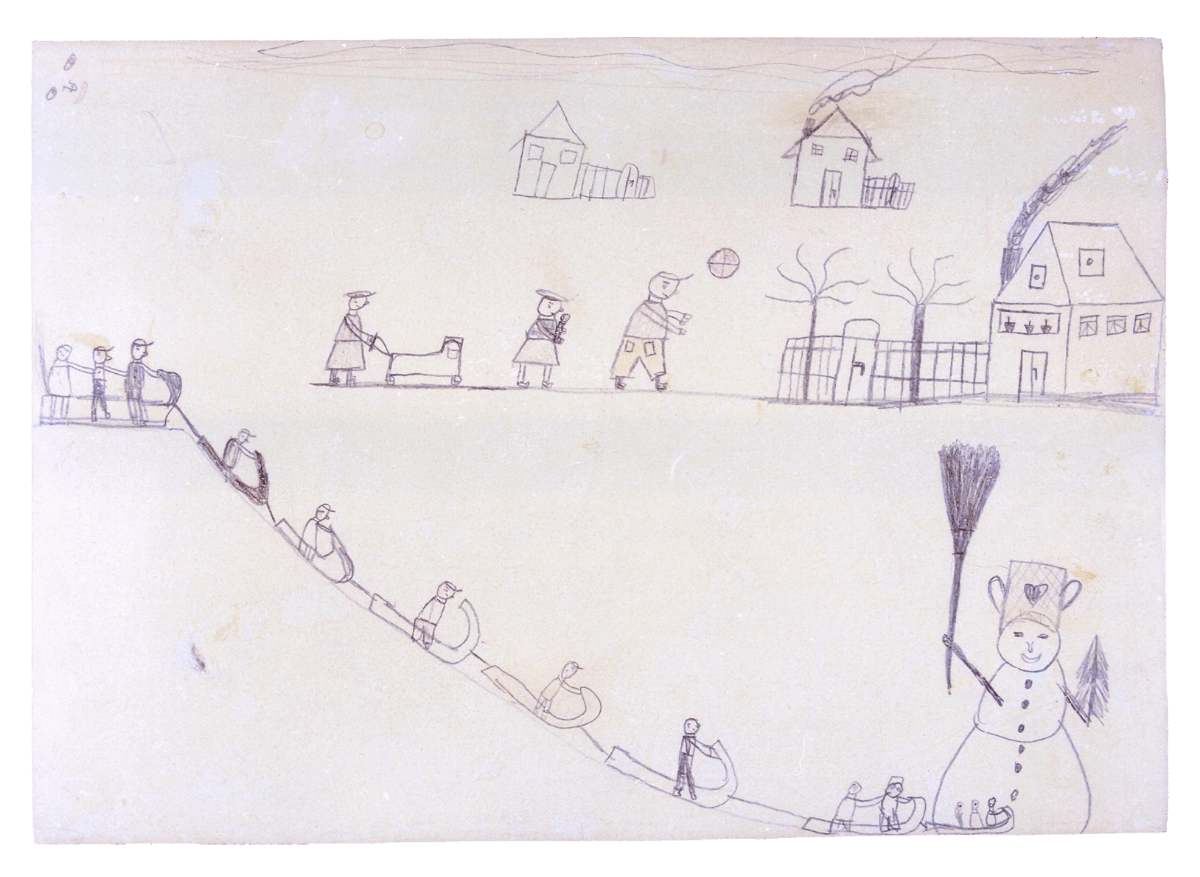

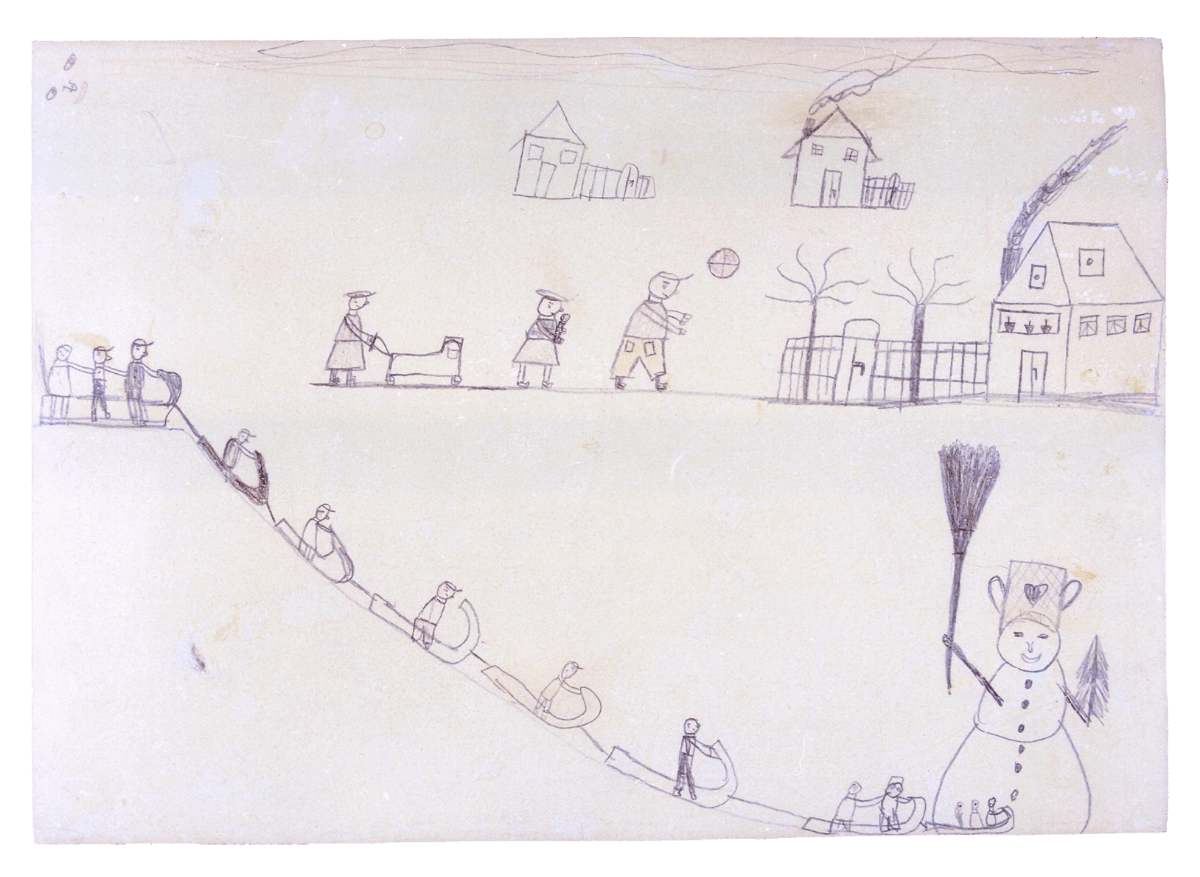

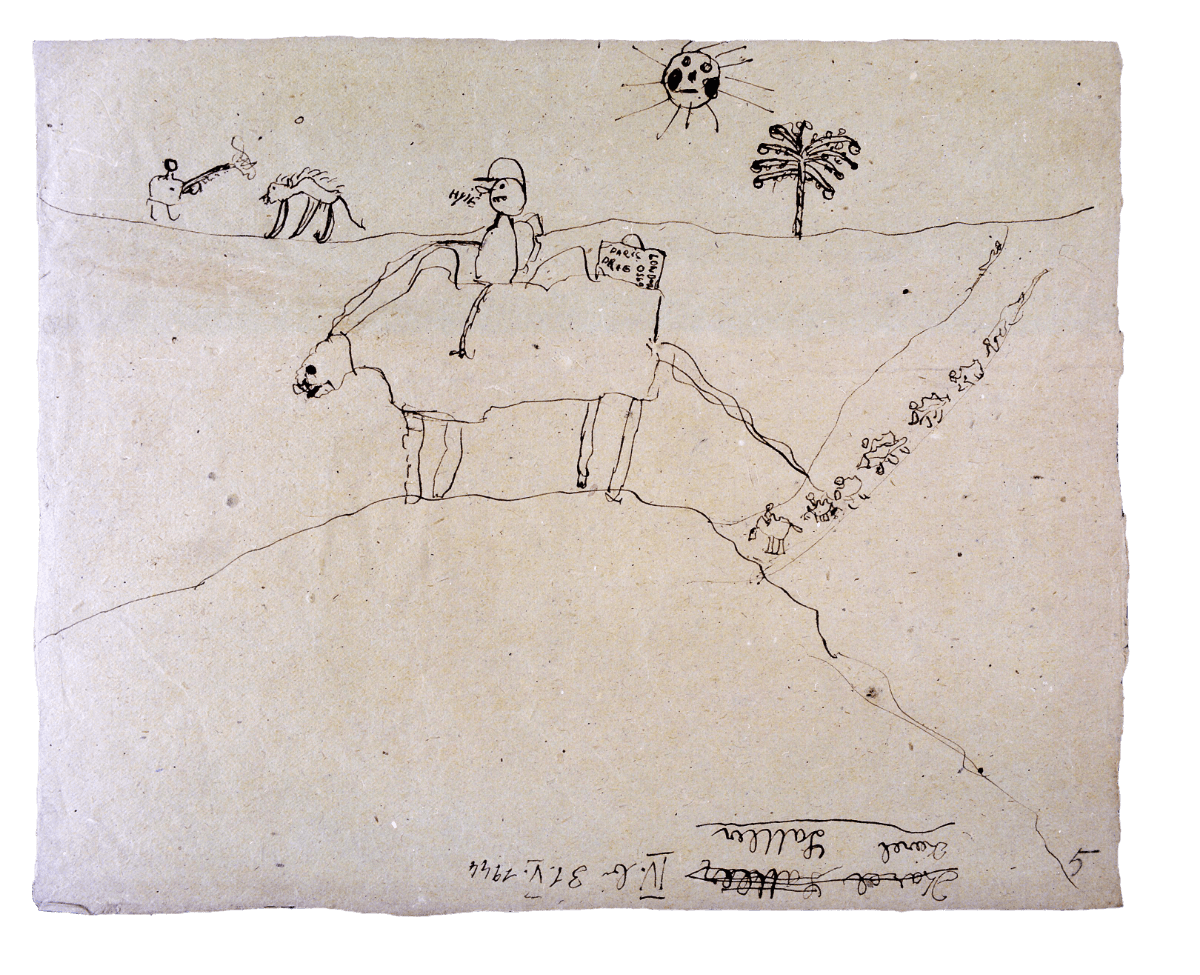

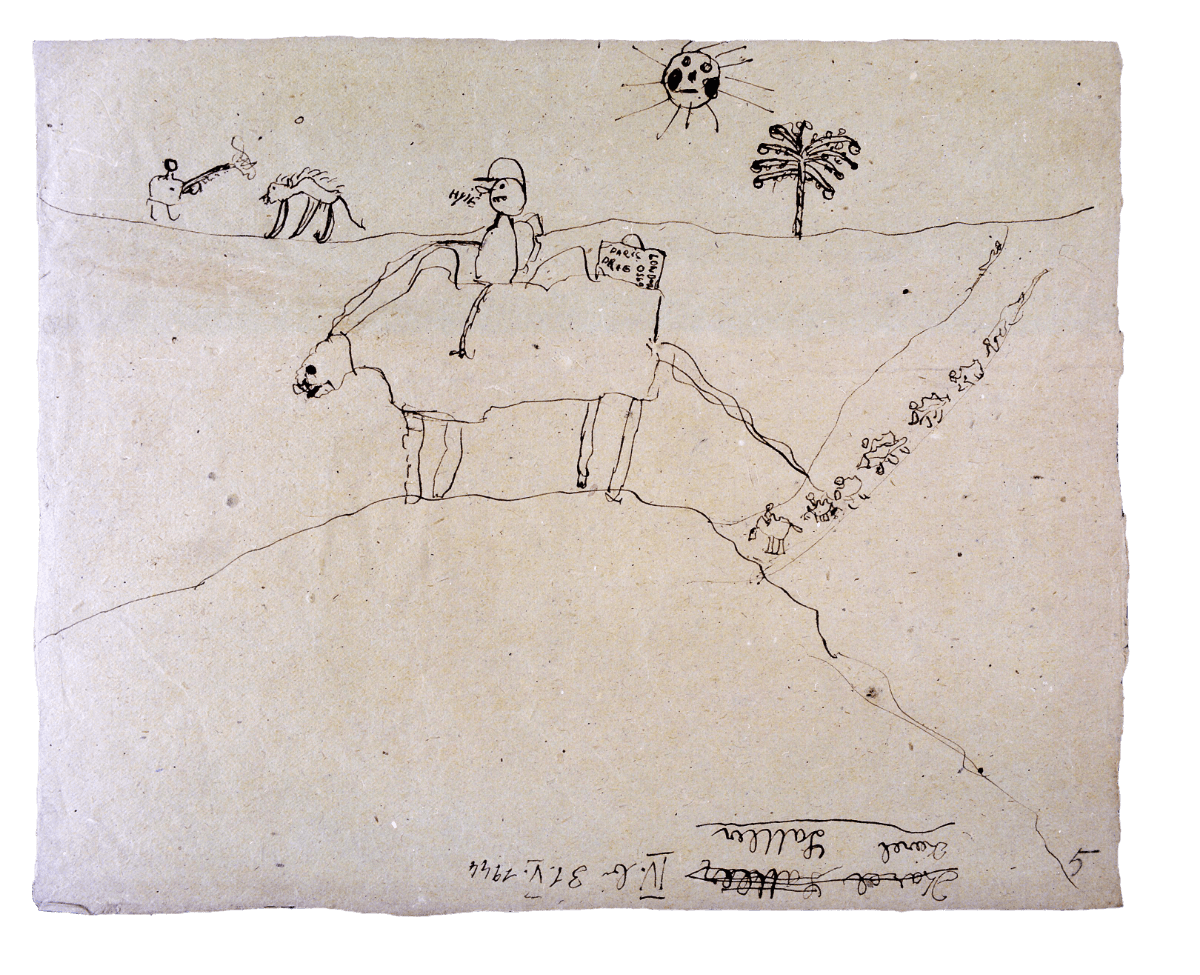

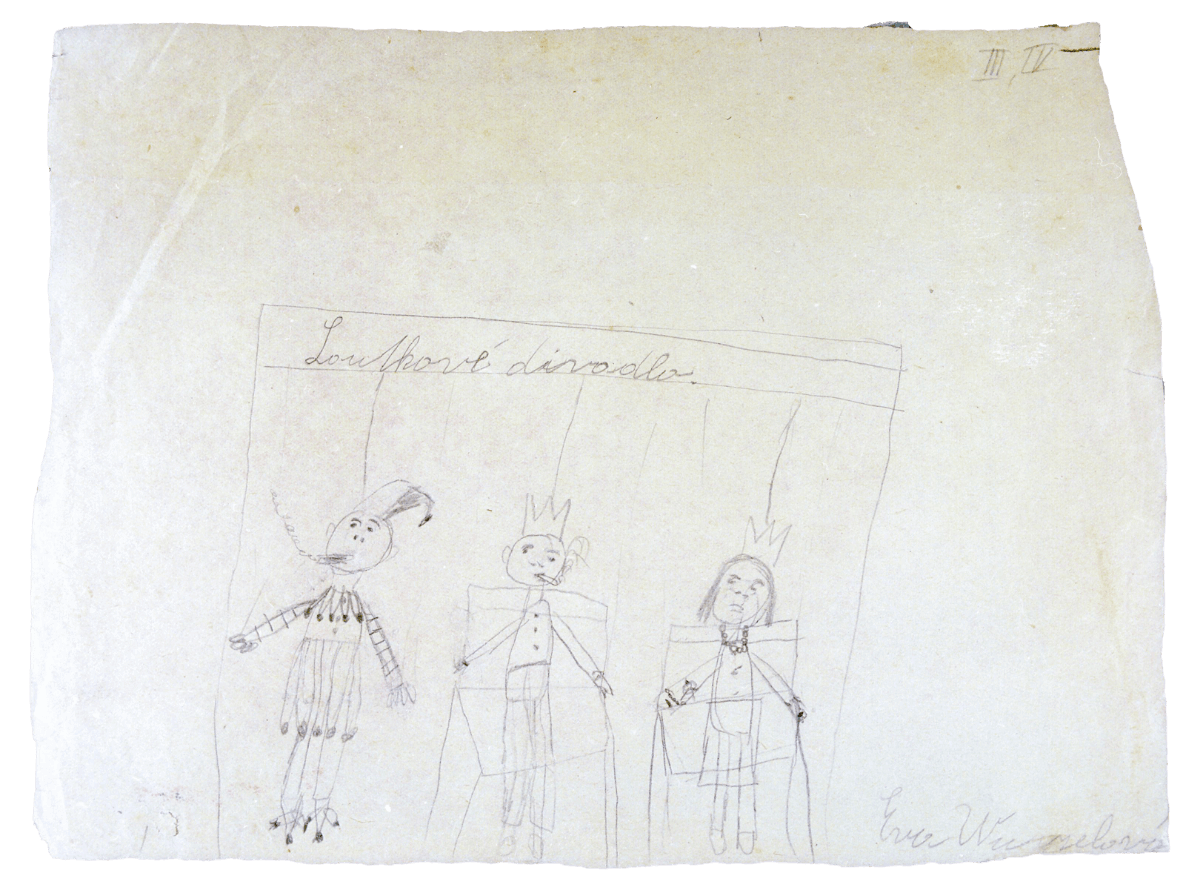

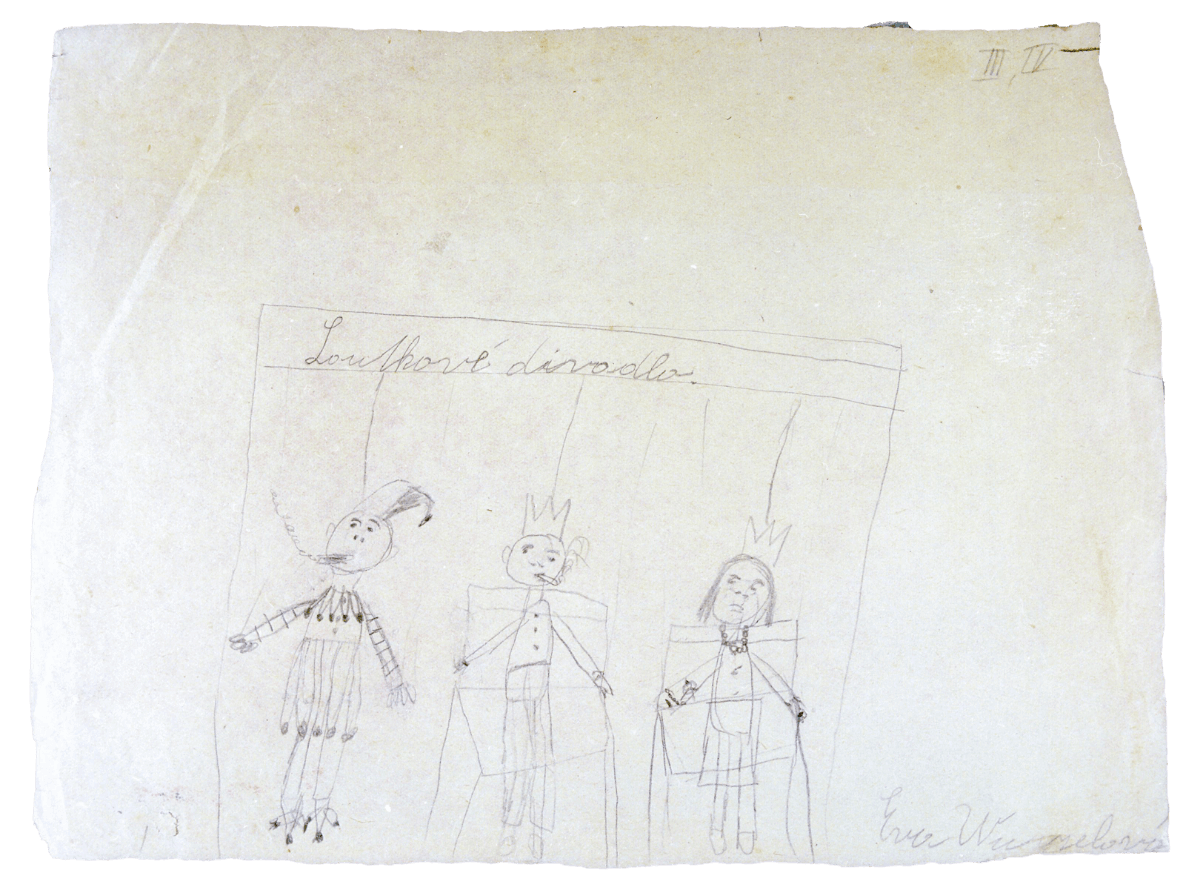

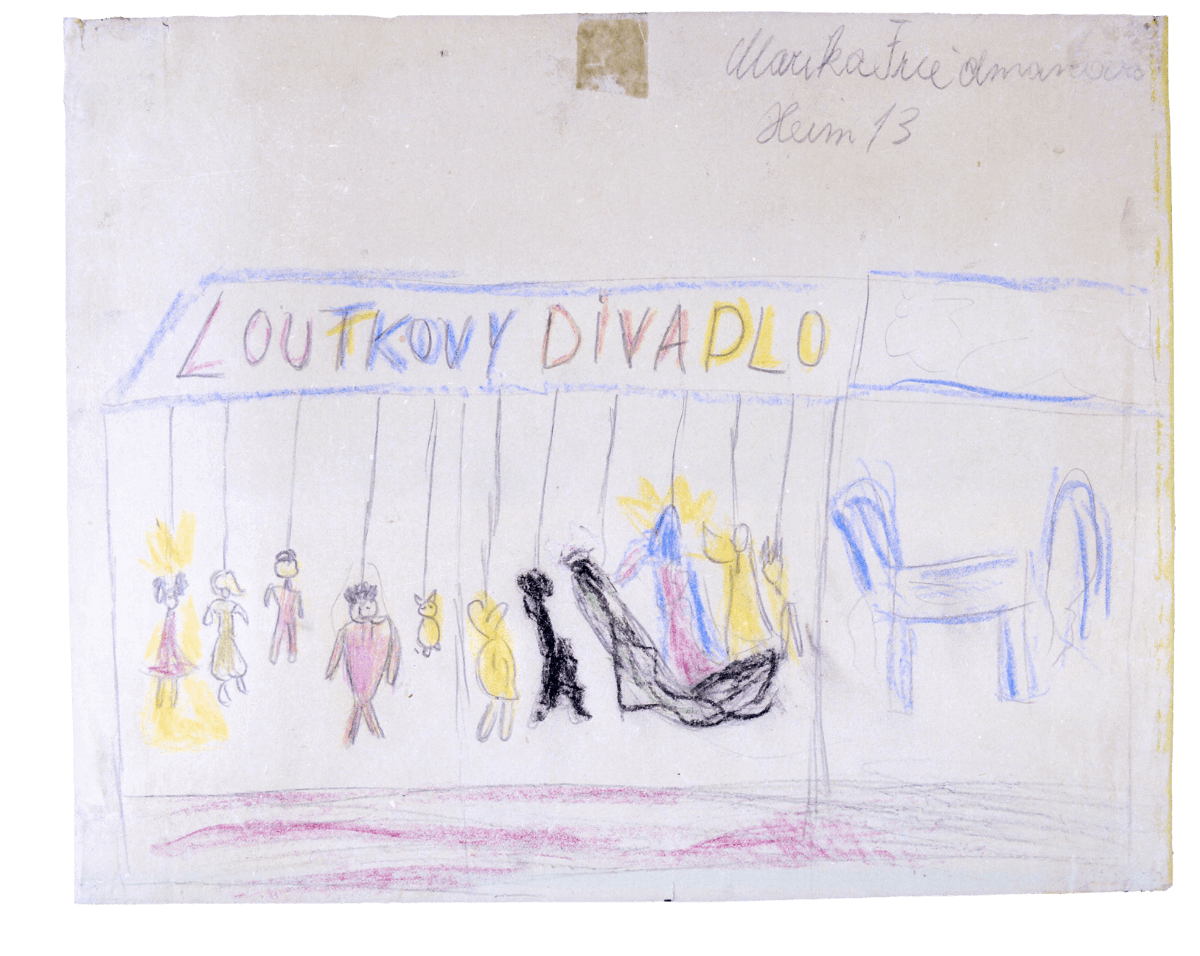

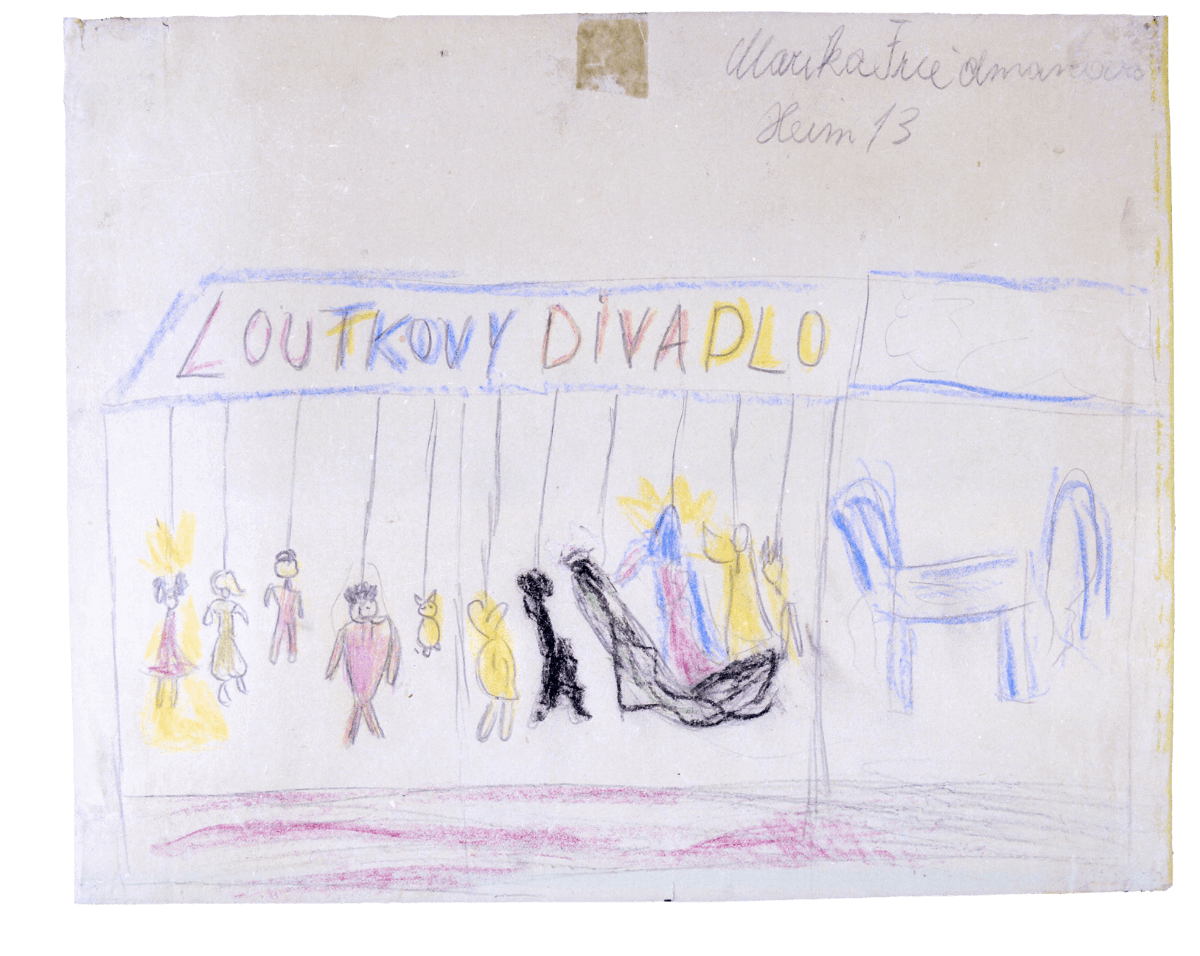

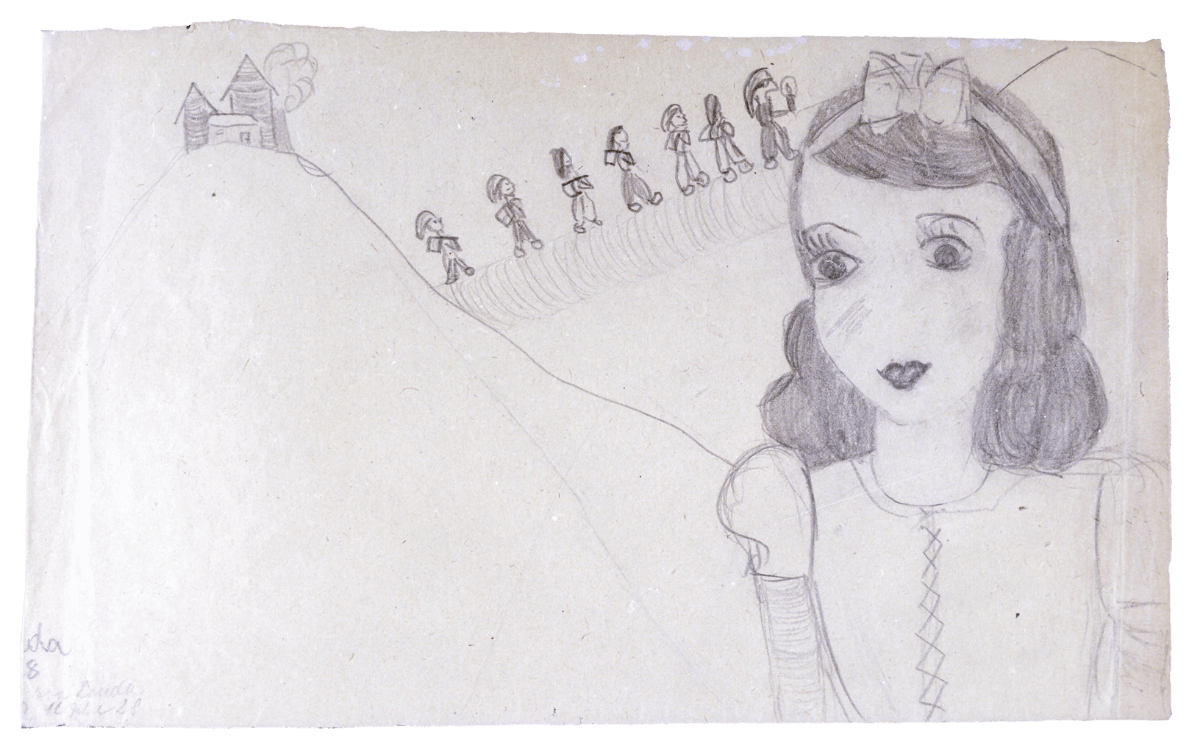

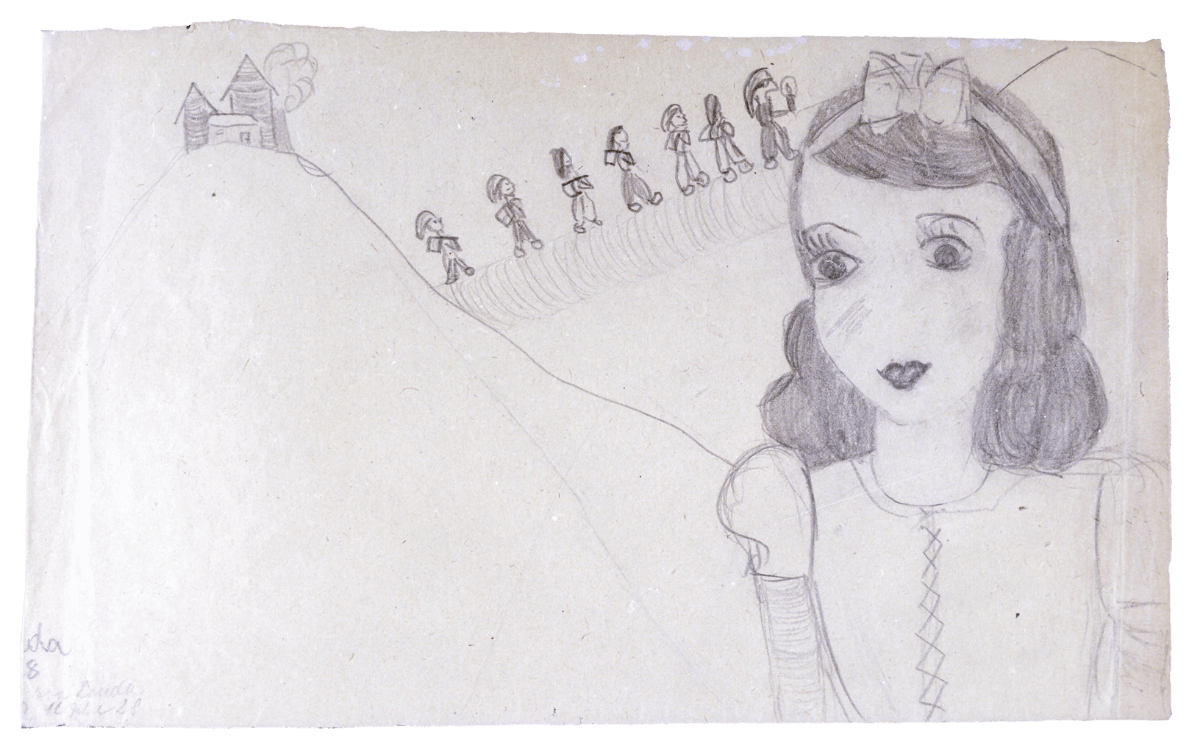

In 1945, after the liberation of the Terezín Ghetto and the German soldiers’ escape, 4,000 drawings were left in the ruins. Under the surveillance of German soldiers, brave adults held secret art classes for children. Even though almost no paper, pencils, or crayons were available, these classes allowed the children not to lose their zest for life and not to give up hope for a brighter tomorrow. What do you feel from the drawings painted in the midst of an unreasonable fear of death?

Commentary by Michiko Nomura

In the Ghetto, German soldiers who believed that “Jews did not need education” allowed Jewish children only to sing songs and play games. Adults stood up to encourage children suffering from hard work, hunger, and the cold—“I will teach Jewish history,” “I will teach beautiful poetry,” and “I will tell stories.” Many others came forward to become teachers; among these, Ms. Friedl Dicker said, “I teach drawing. I believe that drawing will be a zest for life for children.”

Born in Vienna, Friedl loved painting from an early age. She studied at the School of Arts and Crafts and later moved to Germany in 1921 to study at the Bauhaus, the newly established center of the avant-garde art movement. She was involved in sculpture, stage design, stage costumes, textile design, graphic design, other integrated arts, and painting and demonstrated her talent as an artist.

However, with the rise of the Nazis, Friedl, a Jew, was sent to Terezín Ghetto. Only 50 kg of luggage was allowed per family. On the night she received the summon, she gathered all the paper and cloth she could find, dyed some of them in various colors, and packed them into her trunk. She did not know what the camps were like, but she knew that if she met the children, this paper and cloth would be useful. Friedl, who studied art therapy, risked her life by sharing the joy of drawing with children, even in the midst of despair.

The night Friedl received a letter summoning her to Terezín Ghetto, she gathered all the paper she could find in her house, dyed some of it with paint, and put it into her trunk. Each family was allowed up to 50 kg. She did not know what kind of place she would be going to or what kind of life she would have, but she believed that if there were children, this paper would be useful.

Most of the items that each of them had carefully brought were confiscated at the Ghetto entrance, but paper and used paints were allowed to be brought in, probably because they were considered “worthless” by the Nazi SS troops.

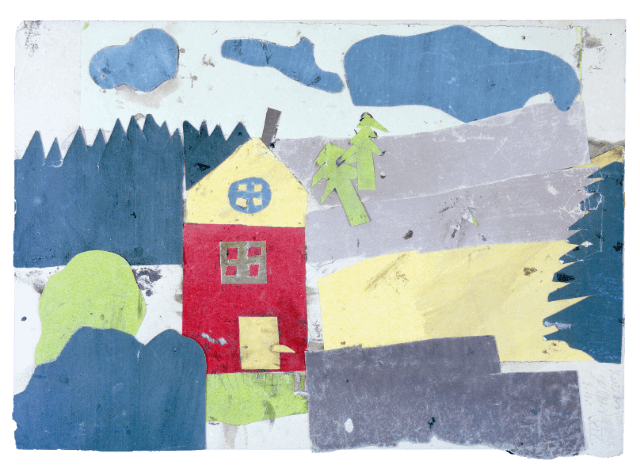

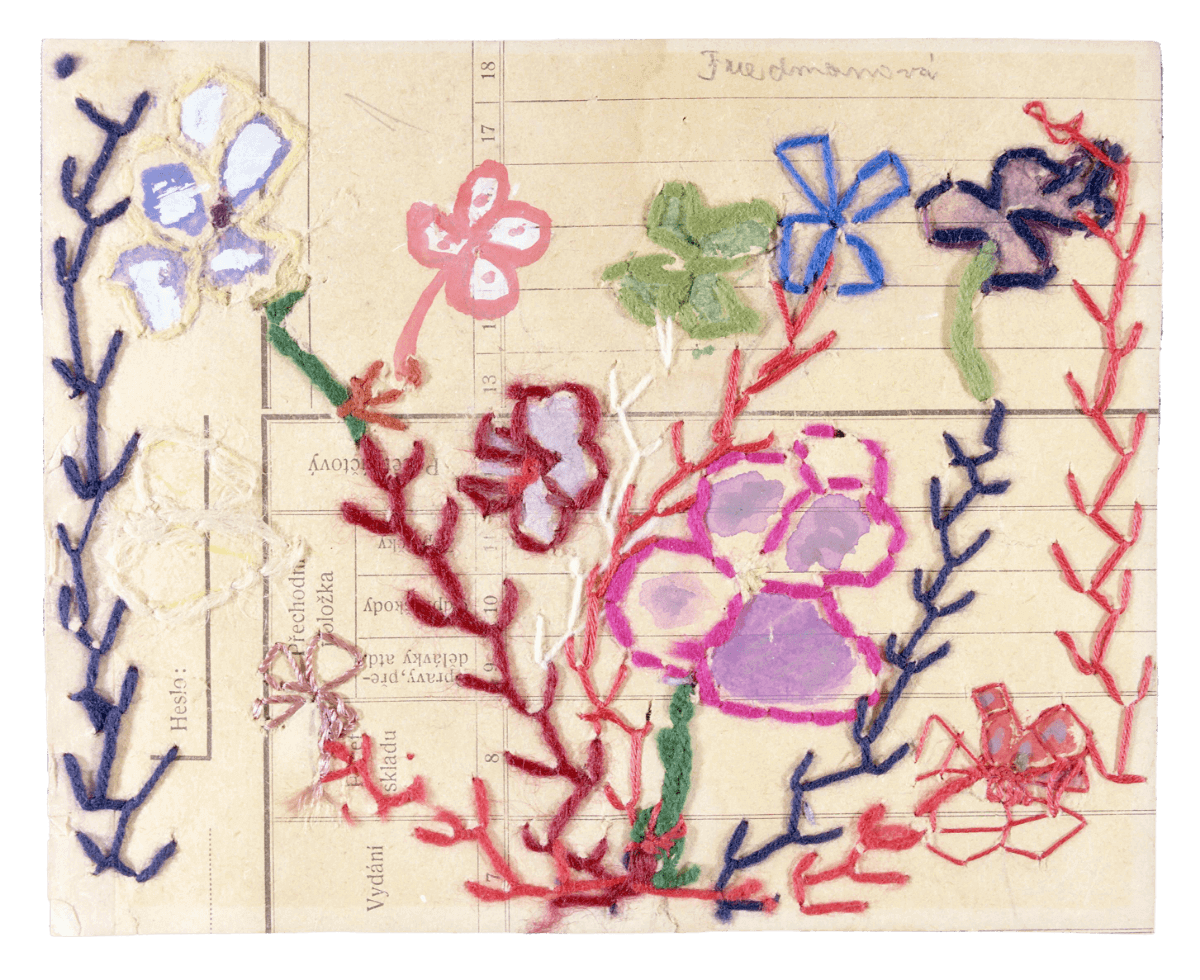

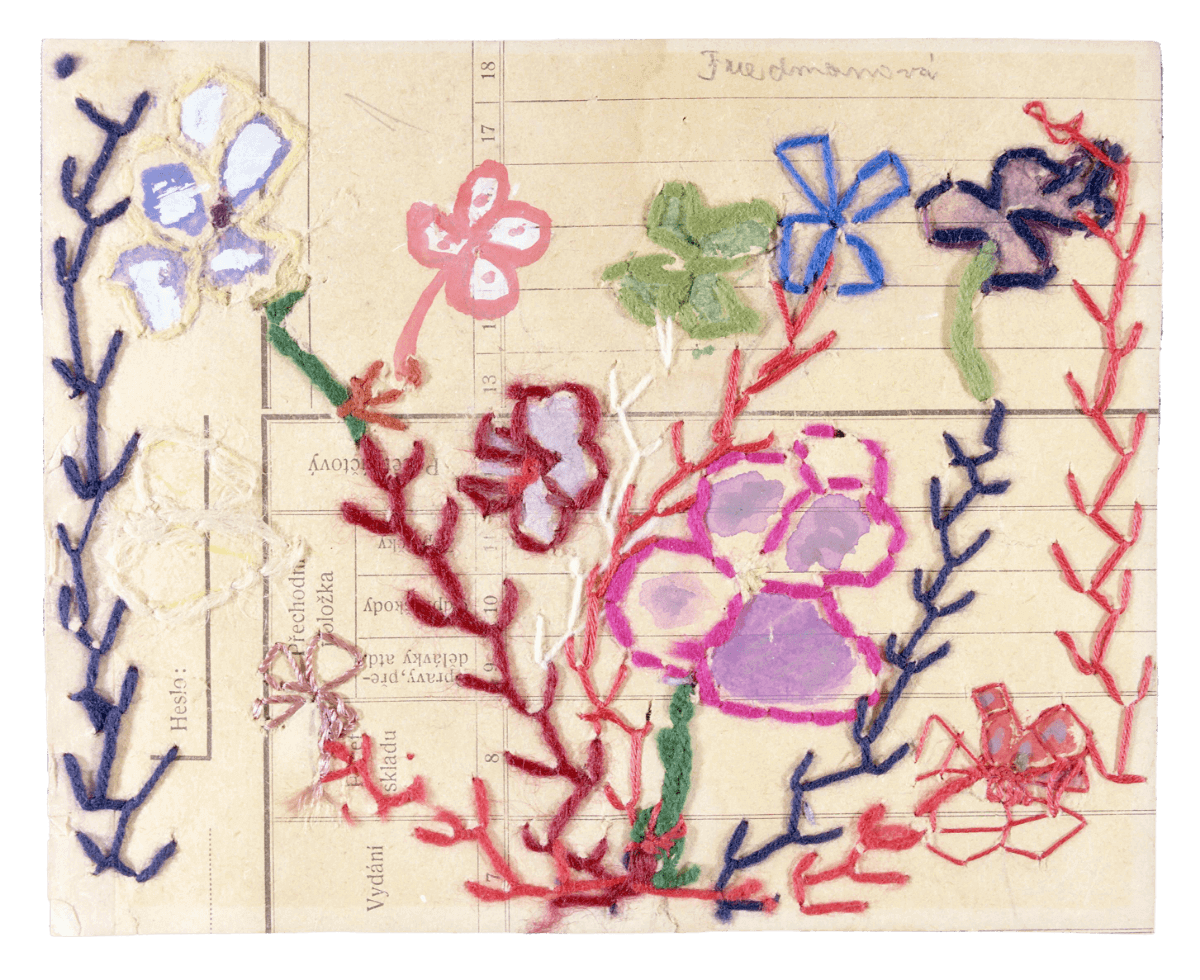

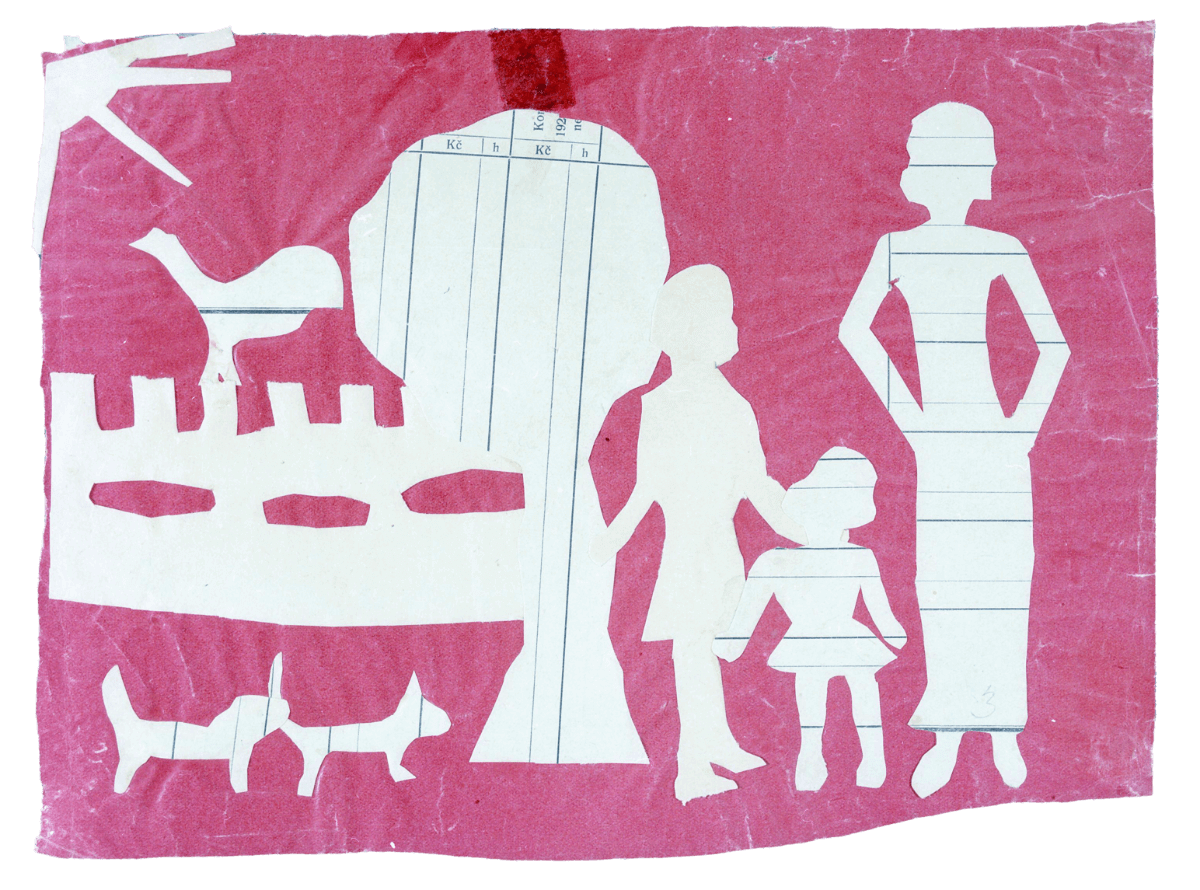

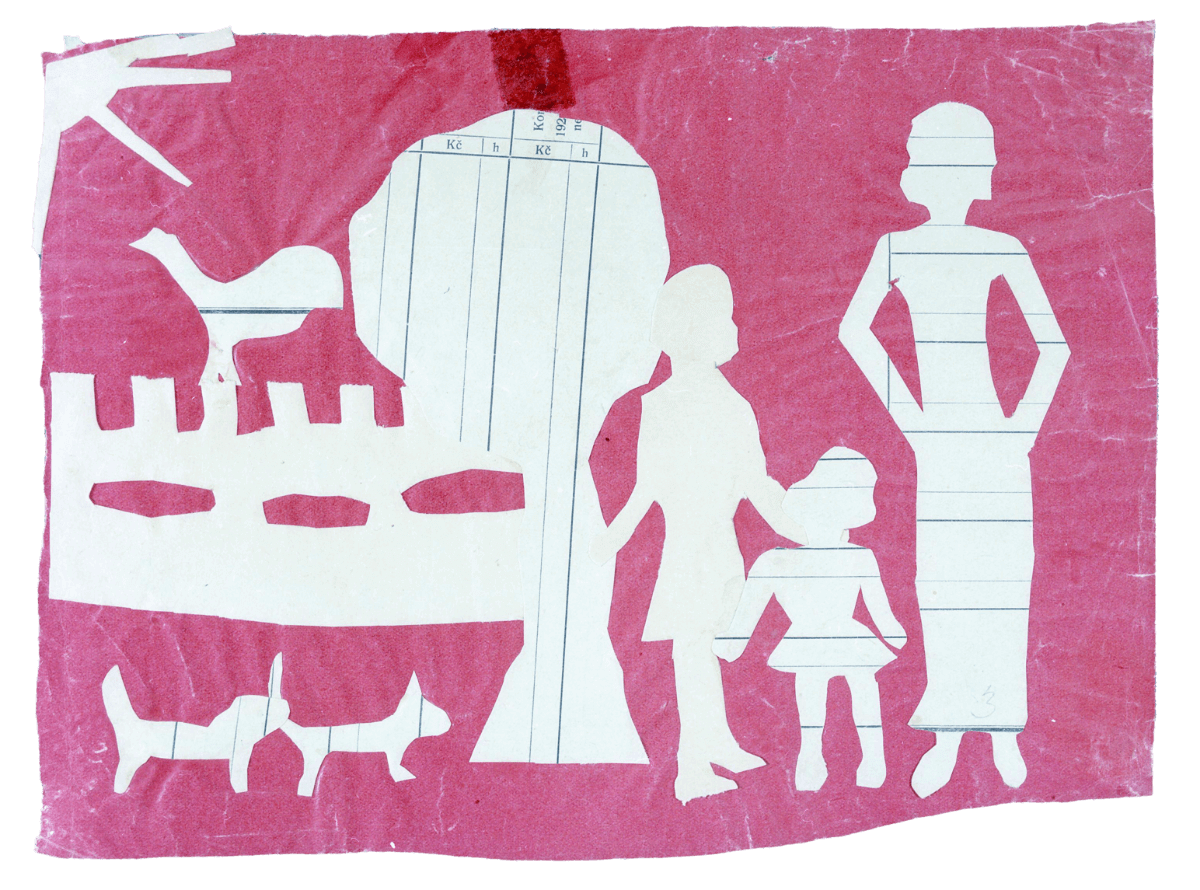

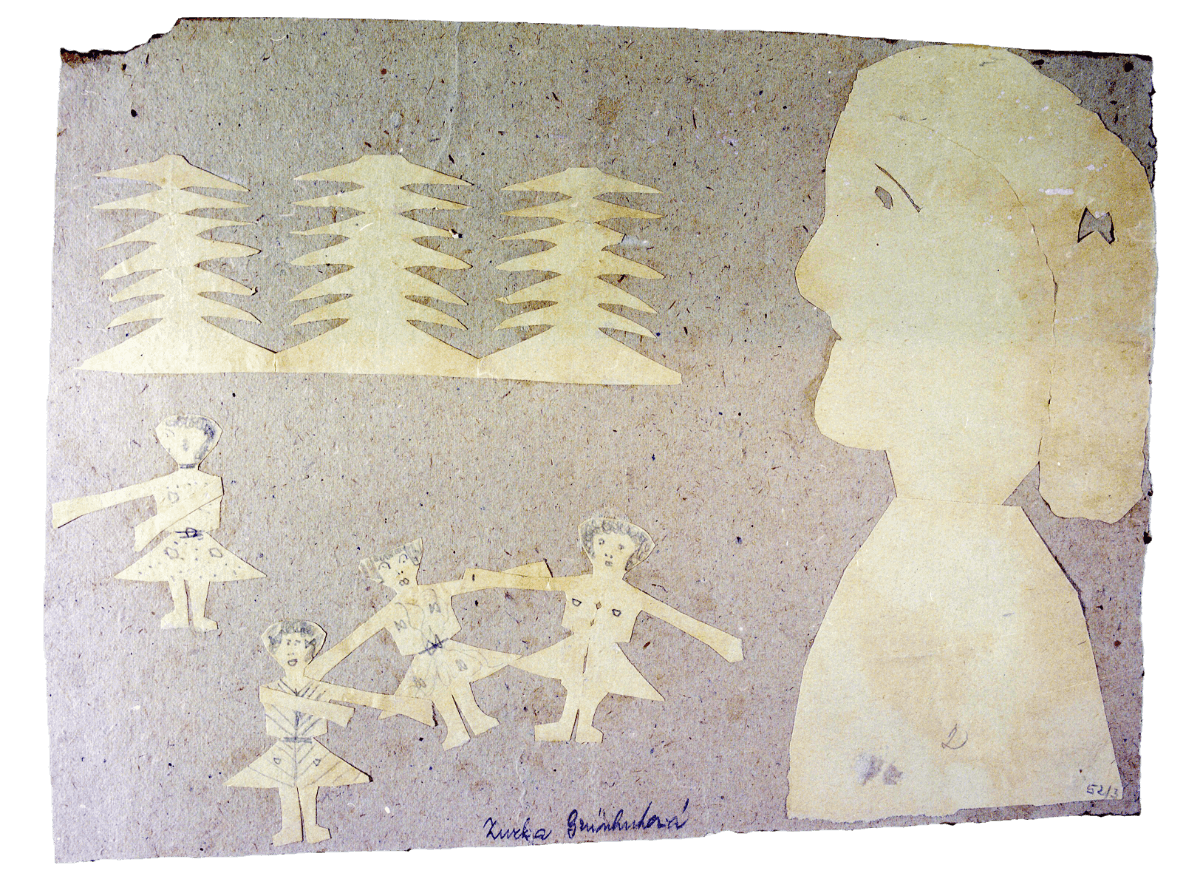

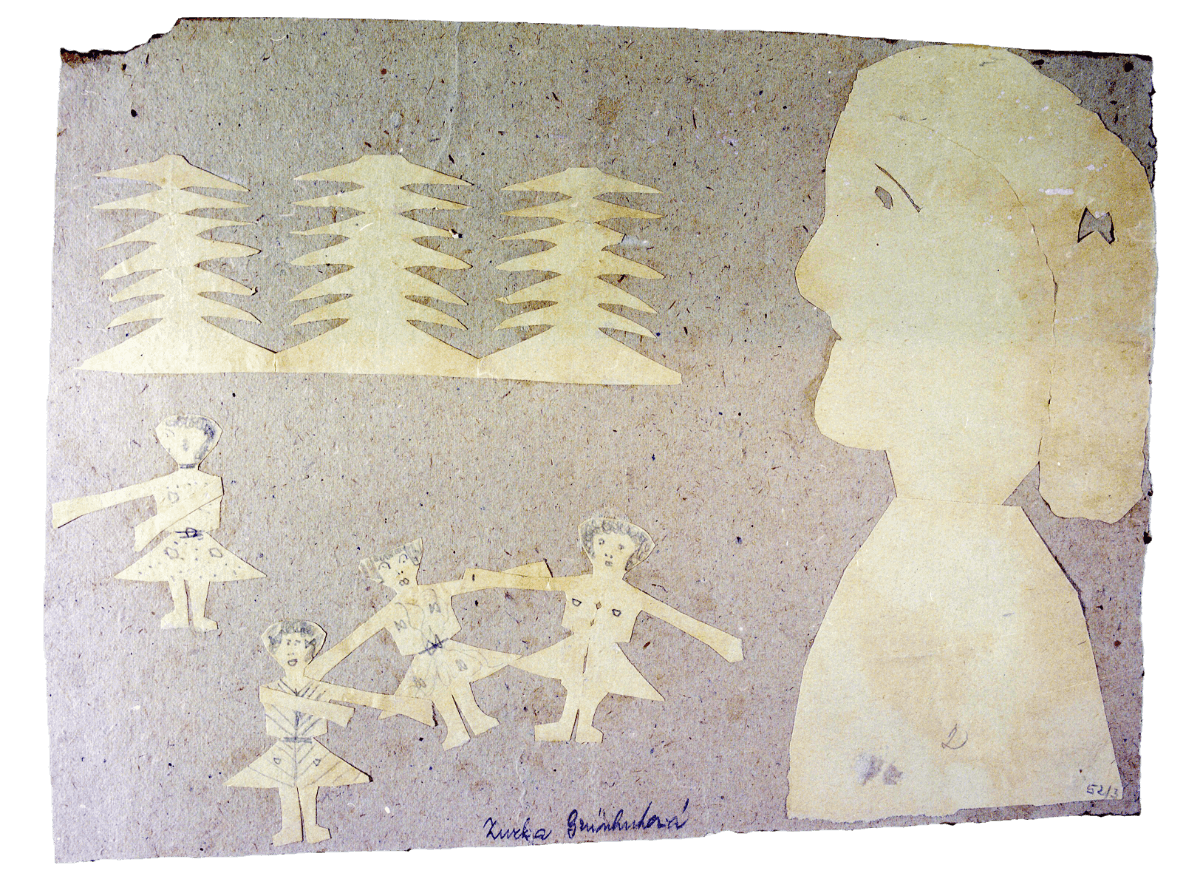

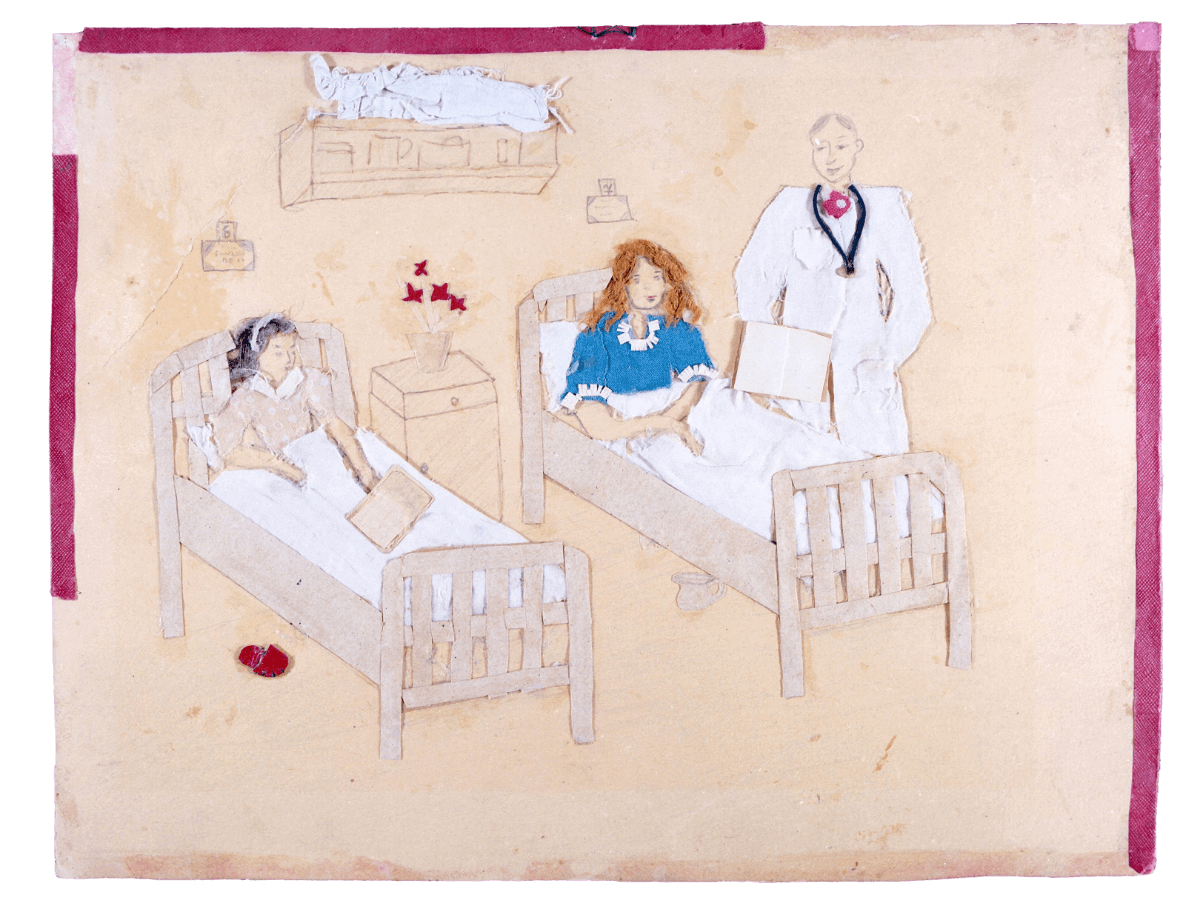

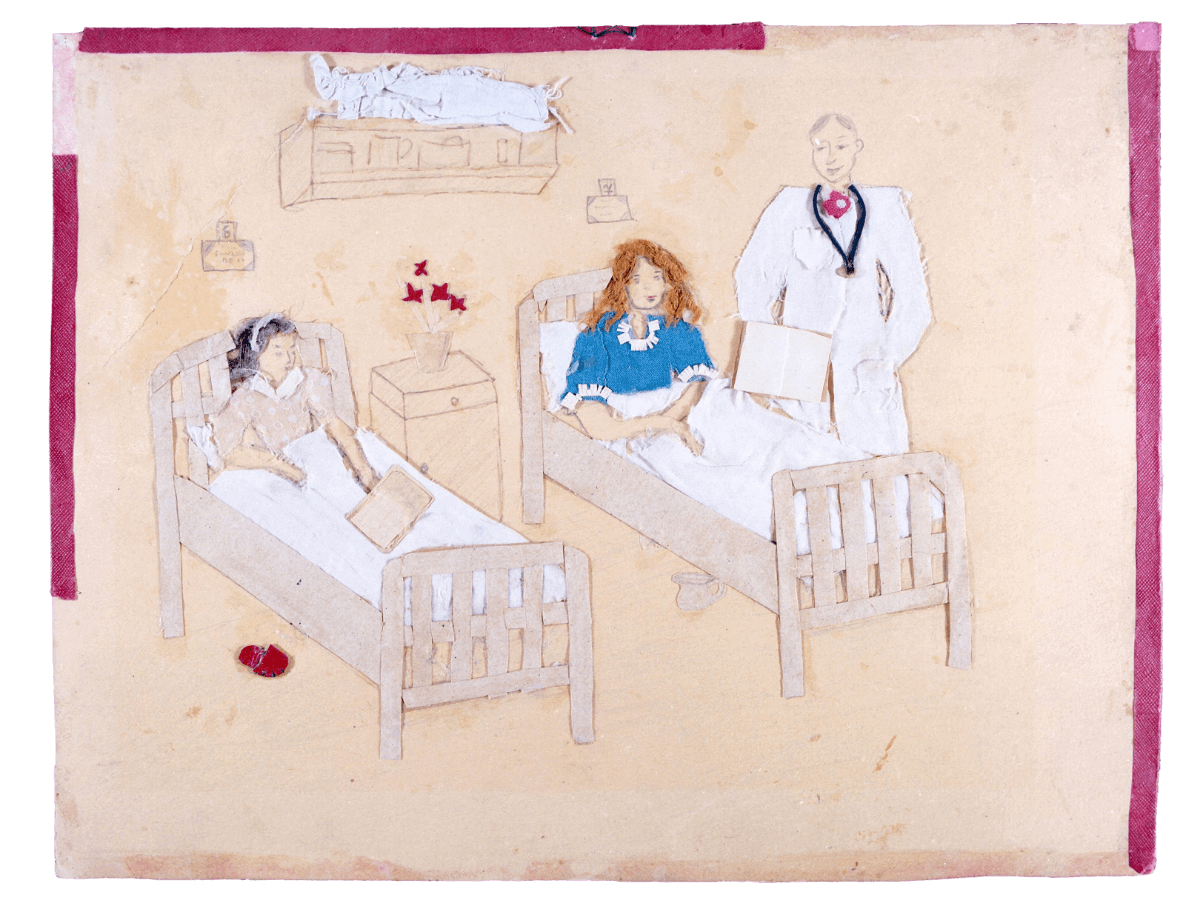

Friedl focused not only on drawing but also on teaching collage work and other art forms. She believed that immersing the children in their creation should help them forget their painful reality.

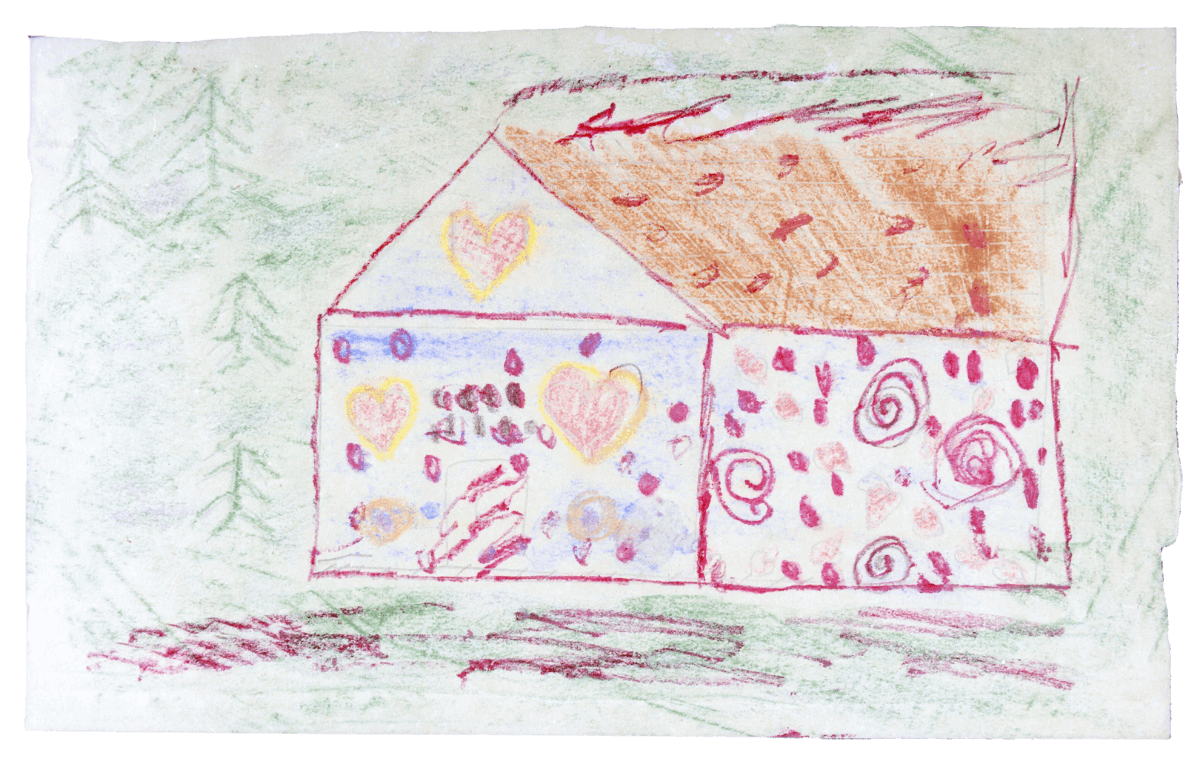

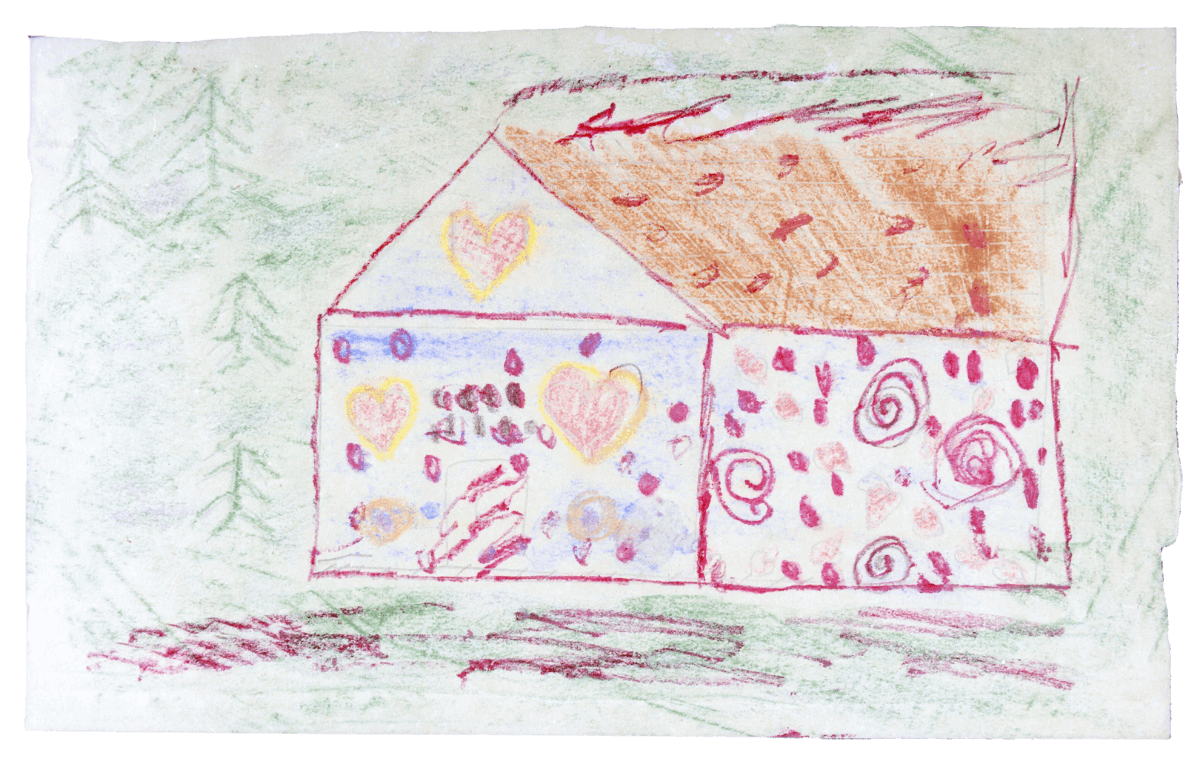

By the time many of the children were able to paint brighter pictures, the few art materials she had brought along had run out. When she talked to the female roommates about the lack of materials, each of them untied the sleeves and hems of their sweaters, gathered the yarn, and offered it to her. Raja Englhnderová (now Zá dniková), one of the surviving children, reminisced about the “warmth” of the yarn in her hands at the time. Documentary papers were probably picked up from the trash by the adult inmates.

Friedl focused not only on drawing but also on teaching collage work and other art forms. She believed that immersing the children in their creation should help them forget their painful reality. By the time many of the children were able to paint brighter pictures, the few art materials she had brought along had run out. When she talked to the female roommates about the lack of materials, each of them untied the sleeves and hems of their sweaters, gathered the yarn, and offered it to her. Raja Englhnderová (now Zá dniková), one of the surviving children, reminisced about the “warmth” of the yarn in her hands at the time. Documentary papers were probably picked up from the trash by the adult inmates.

Friedl focused not only on drawing but also on teaching collage work and other art forms. She believed that immersing the children in their creation should help them forget their painful reality.

By the time many of the children were able to paint brighter pictures, the few art materials she had brought along had run out. When she talked to the female roommates about the lack of materials, each of them untied the sleeves and hems of their sweaters, gathered the yarn, and offered it to her. Raja Englhnderová (now Zá dniková), one of the surviving children, reminisced about the “warmth” of the yarn in her hands at the time. Documentary papers were probably picked up from the trash by the adult inmates.

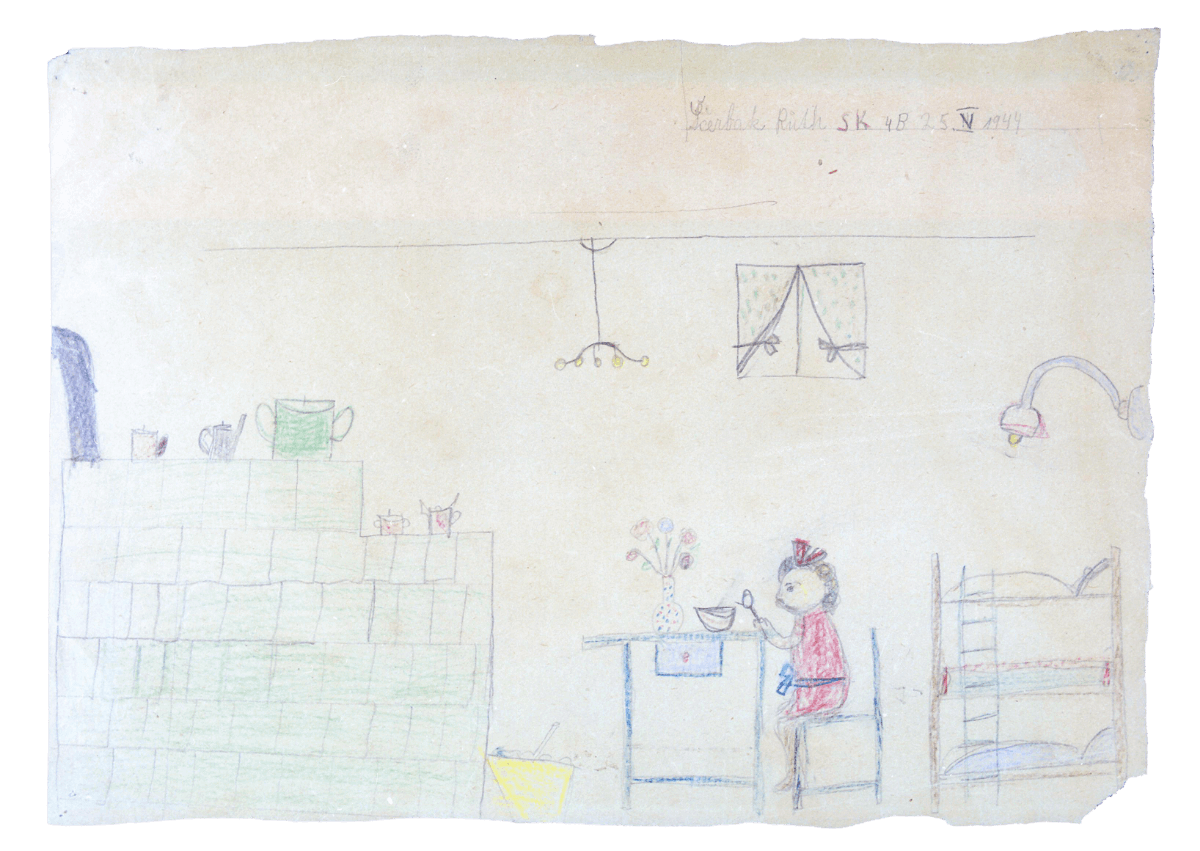

At one elementary school, when I showed this drawing, one student said, “It would look more fun with darker paints.” When I explained that the picture was painted in an internment camp, the student said, “The girl/boy wanted to paint with darker colors, but she/he didn’t have enough paint, right?”

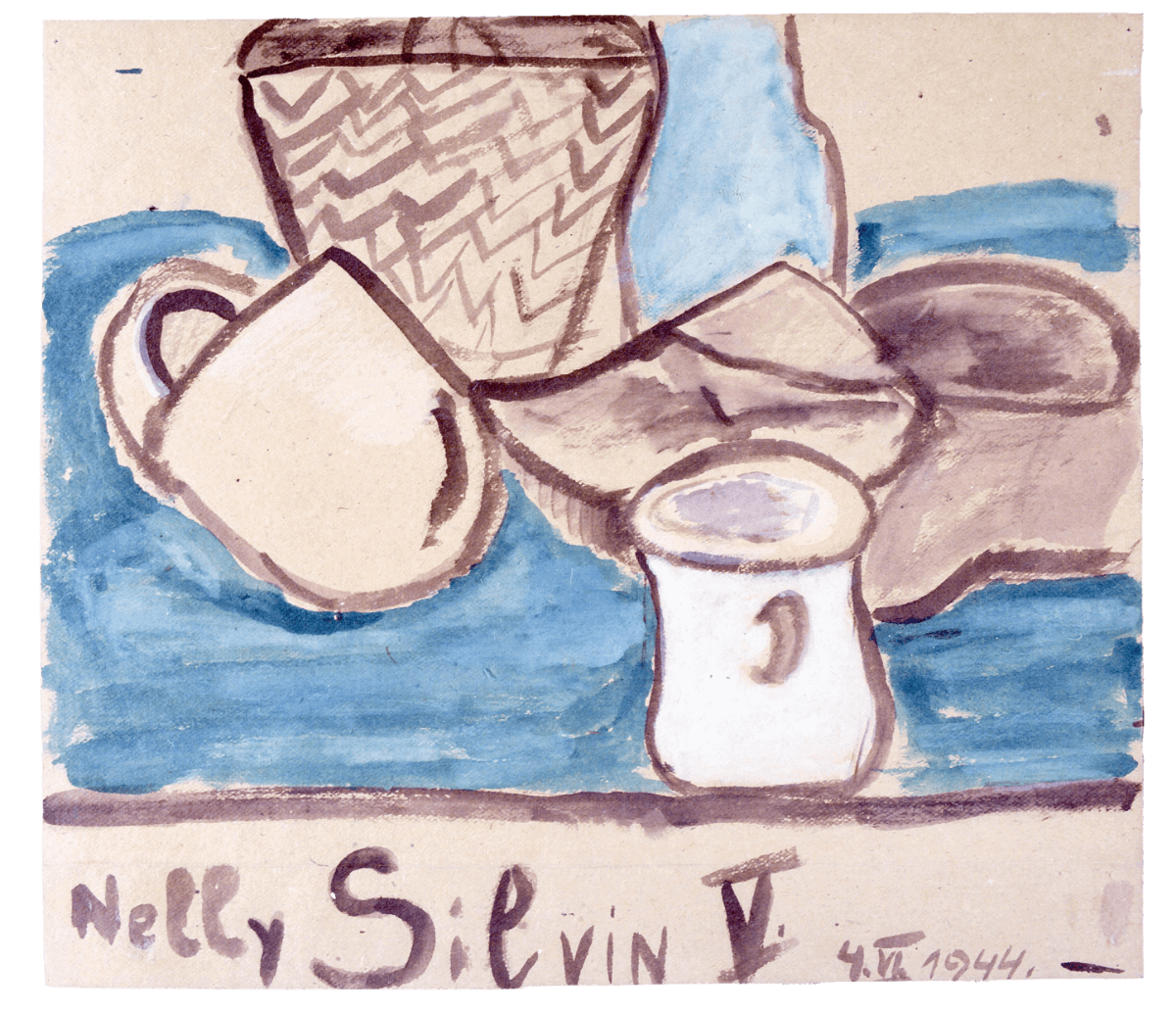

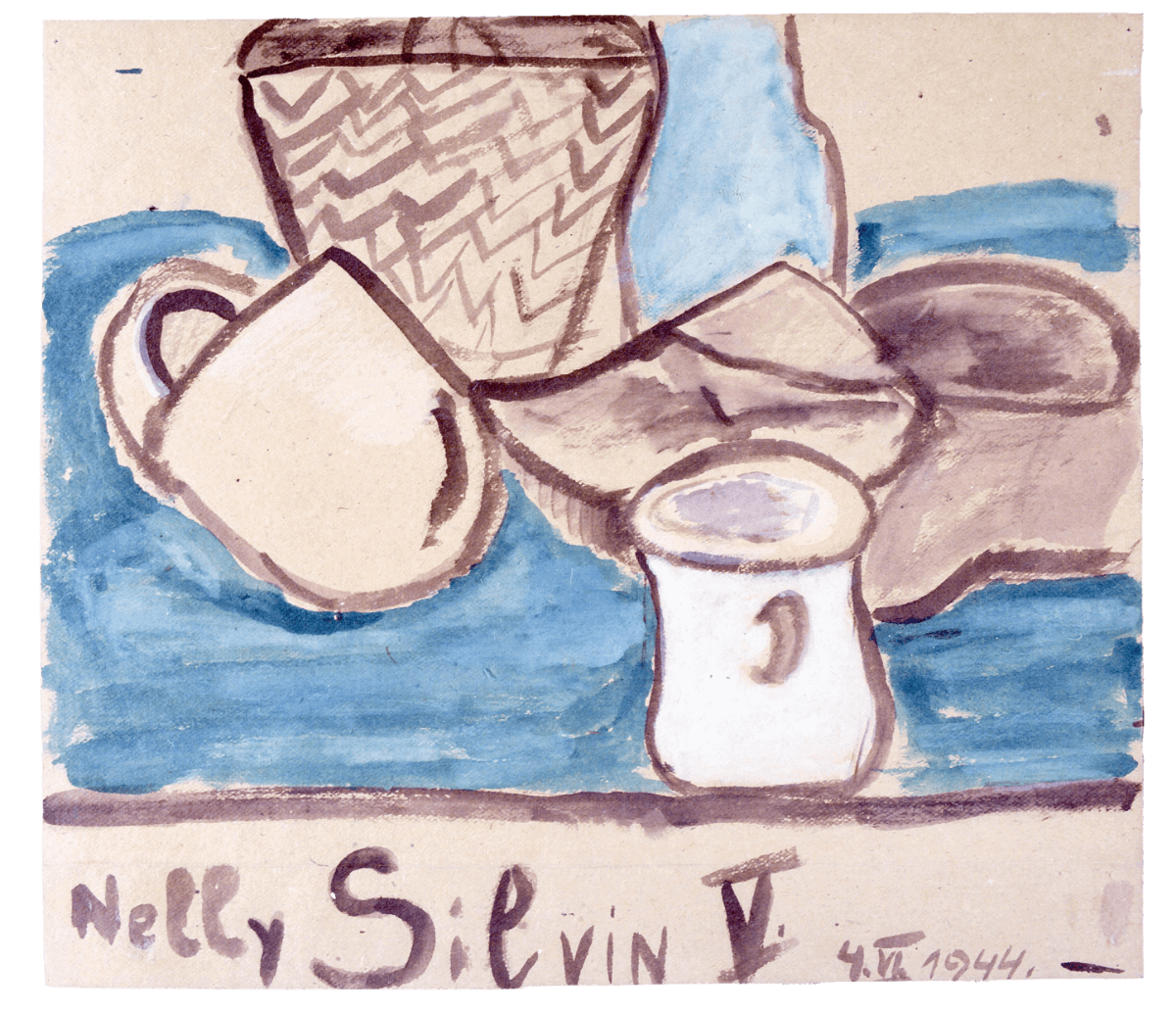

Friedl, born in Vienna in 1898, had loved drawing and kneading clay from an early age. At a time when culture and art were flourishing, paintings by Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele were often seen in the city. Friedl, whose mother had died when she was very young, hung out at the large stationery store where her father worked, looking through art books and exhibition posters intently. She entered graphic design school at the age of 16 to get a basic education.

I (Michiko Nomura) wonder if the reason she collected the few still-life objects in the Ghetto and had the children paint them was because she wanted them to receive the same education that she herself had received.

Friedl, born in Vienna in 1898, had loved drawing and kneading clay from an early age. At a time when culture and art were flourishing, paintings by Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele were often seen in the city. Friedl, whose mother had died when she was very young, hung out at the large stationery store where her father worked, looking through art books and exhibition posters intently. She entered graphic design school at the age of 16 to get a basic education.

I (Michiko Nomura) wonder if the reason she collected the few still-life objects in the Ghetto and had the children paint them was because she wanted them to receive the same education that she herself had received.

At the time of the national touring exhibition in 1991, the Jewish Museum in the Czech Republic initially said that it was impossible to lend the originals because the drawings were deteriorating and that they would provide the photographic film for making replicas. However, I (Michiko Nomura) repeatedly asked the museum to lend me the original works, saying that I wanted to show visitors the deterioration of the artworks and the fact that they were painted on discarded paper; finally, six of them were exhibited, one of which is this drawing.

It is a collage work pasted on a piece of cardboard that looks like a boxlid.

The head of the girl on the left side of the drawing is made of human hair. Angela, the curator of the Jewish Museum at the time, said, “The author of the drawing probably used yarn for the hair of the girl on the right and ran out of it.” I assume that the author penciled in the doctor’s hair for the left girl’s head, they cut their own hair and attached them because they wanted real hair on the girl’s head.

This work is unfinished; I imagine that they would have liked to make a more detailed bedside, table, and so on if they had had colored paper. They would have signed it once it was all done. However, I suspect that the artist could no longer attend the art class and is thus unknown. Only a few hairs have become proof of this artist’s life in this world.

Friedl told the children, “When you draw a picture, be sure to write your name at the end. The German soldiers call you by your numbers, but that is not right. Each of you has a name that your parents gave you because they loved you.” Many of the works listed as “author unknown” are unfinished.

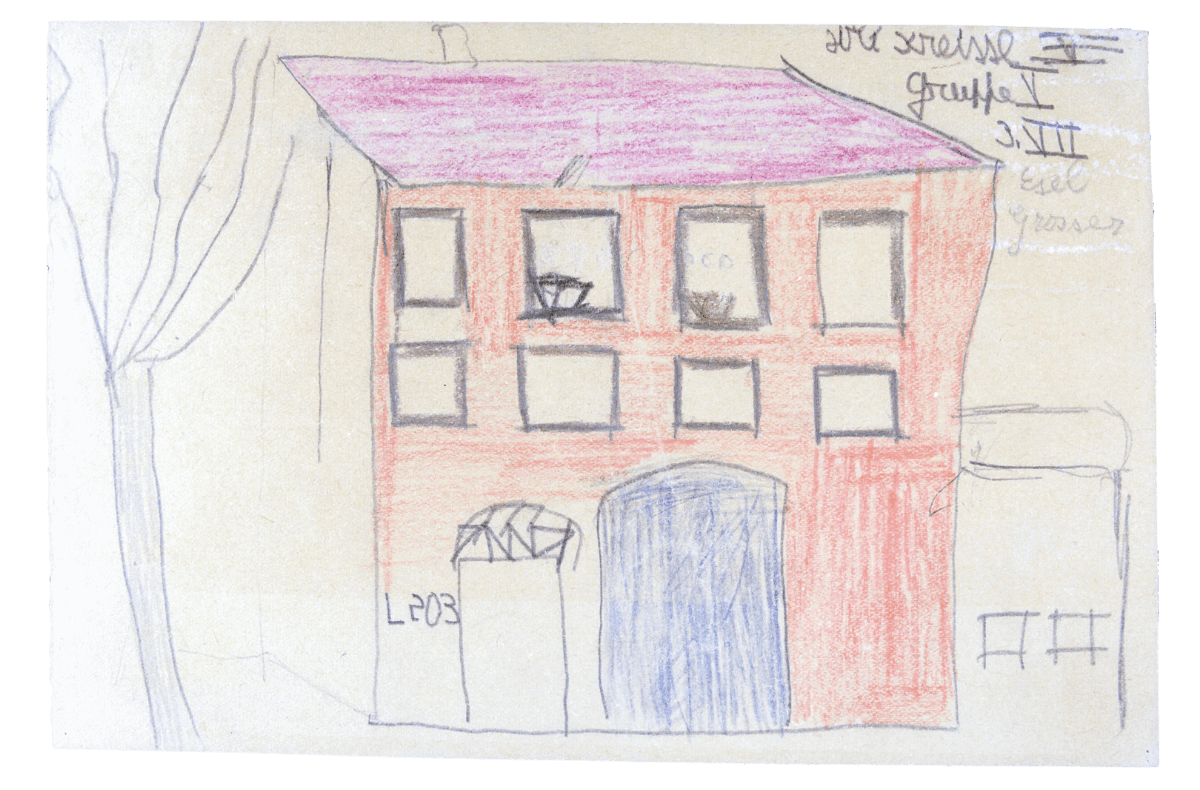

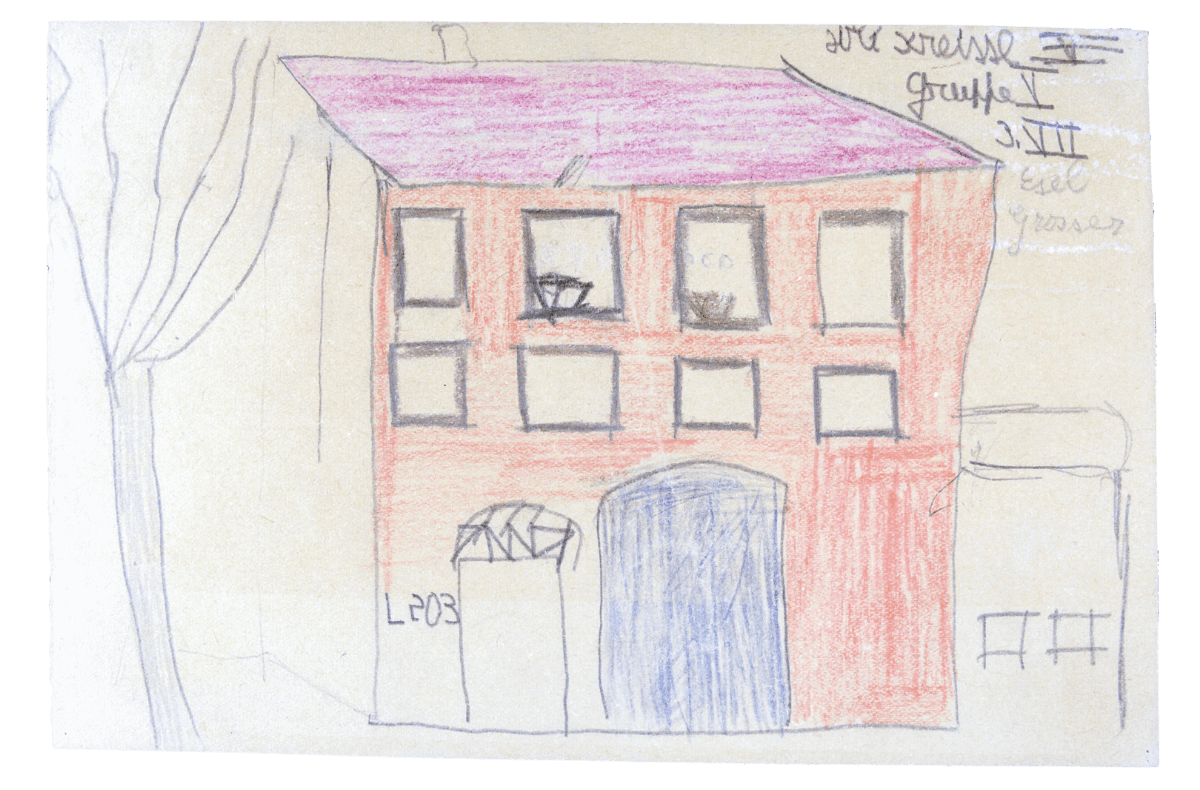

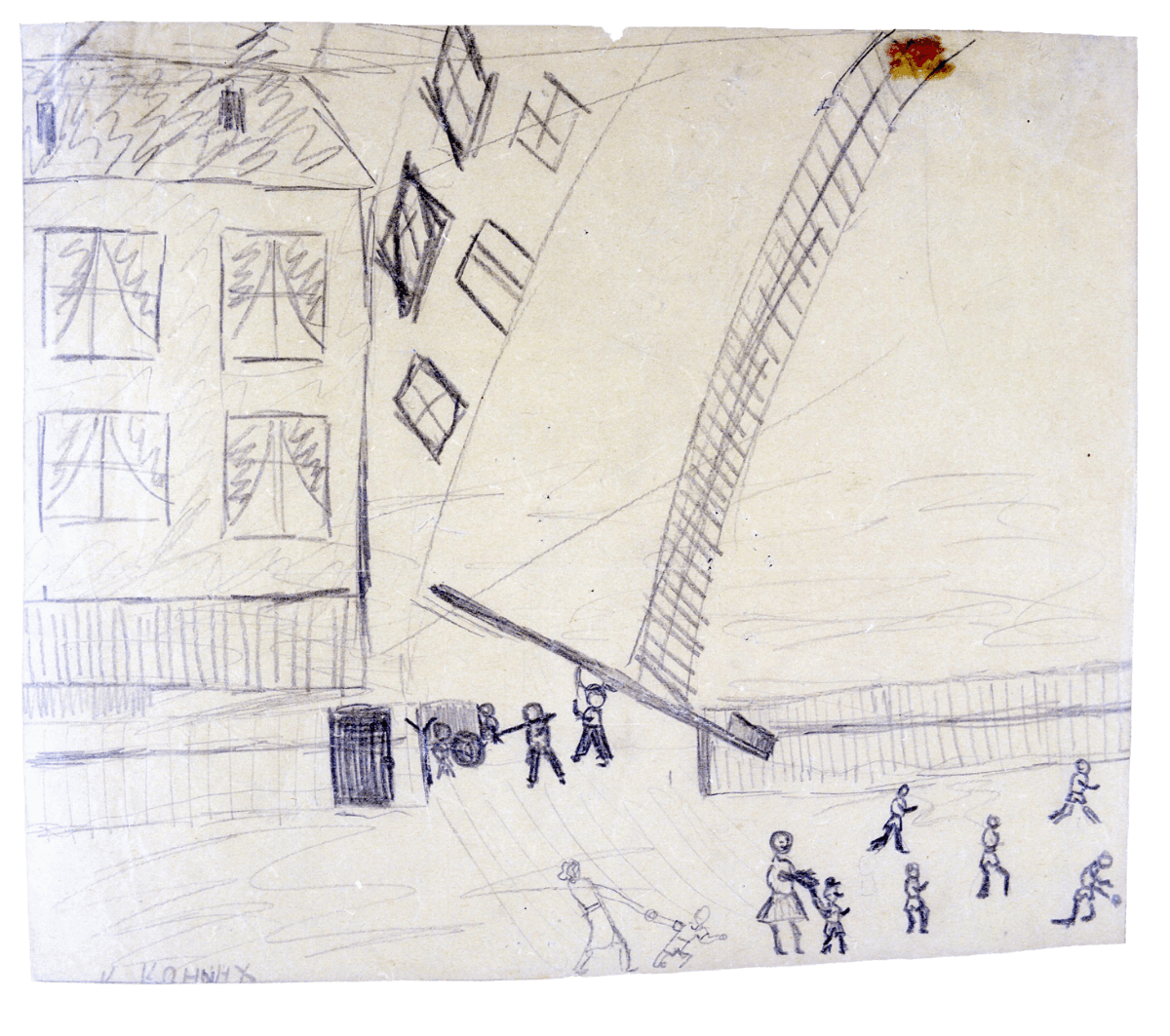

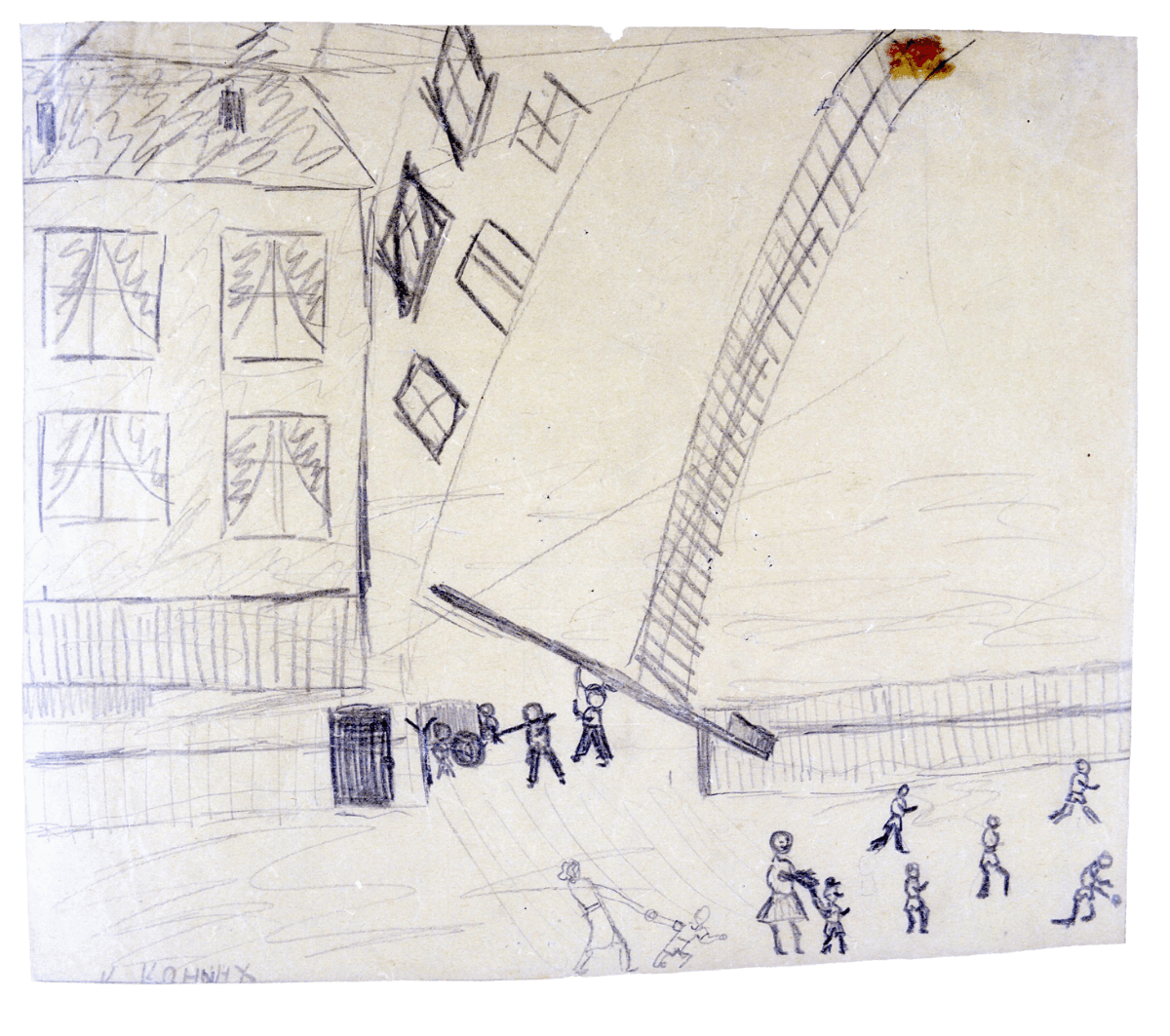

In 1942, the “normal town” of Terezín, located about 30 miles north of Prague, became a Theresienstadt Camp/Ghetto by order of Reinhard Heydrich, the chief lieutenant in the Schutzstaffel. The apartments, stores, banks, and post offices were all converted into buildings of the camp. The “Girls’ Home” was originally an apartment building and is still used today as an “ordinary house” in an “ordinary town.”

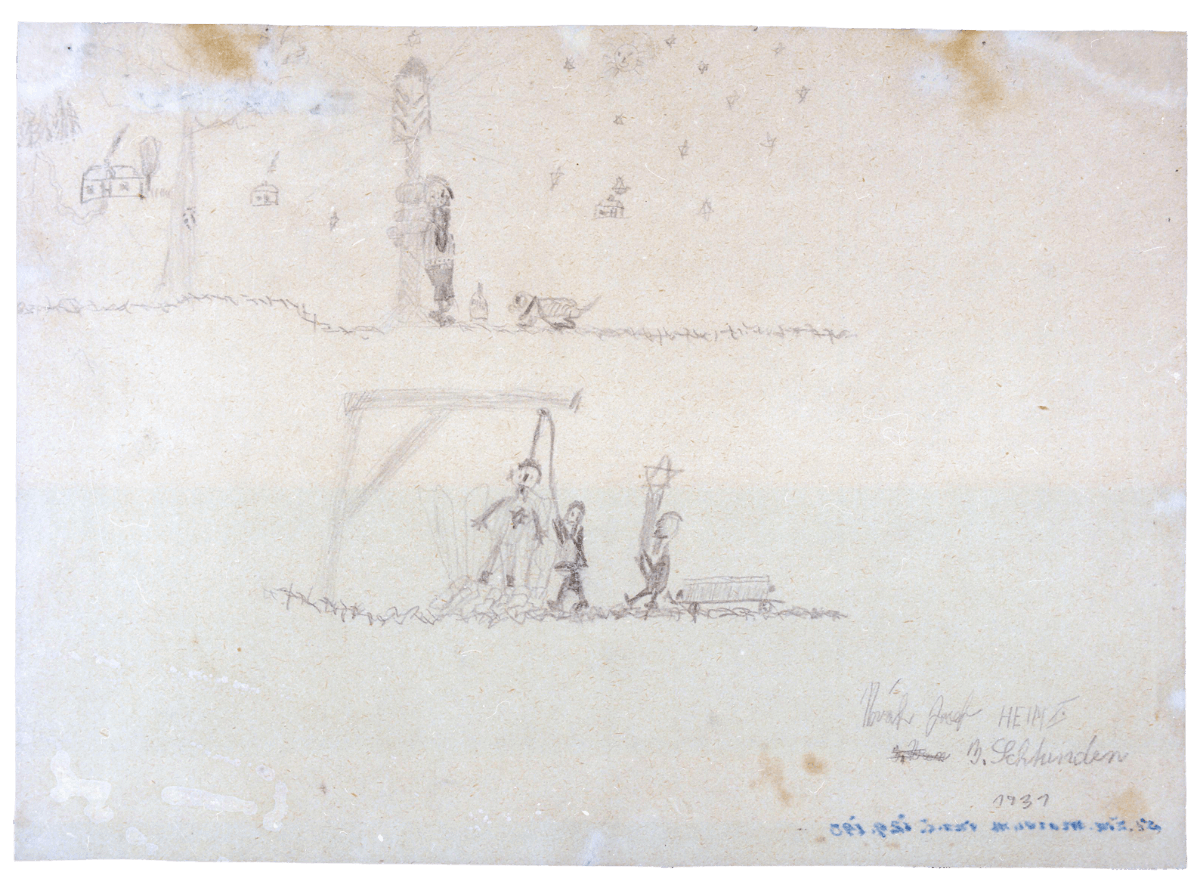

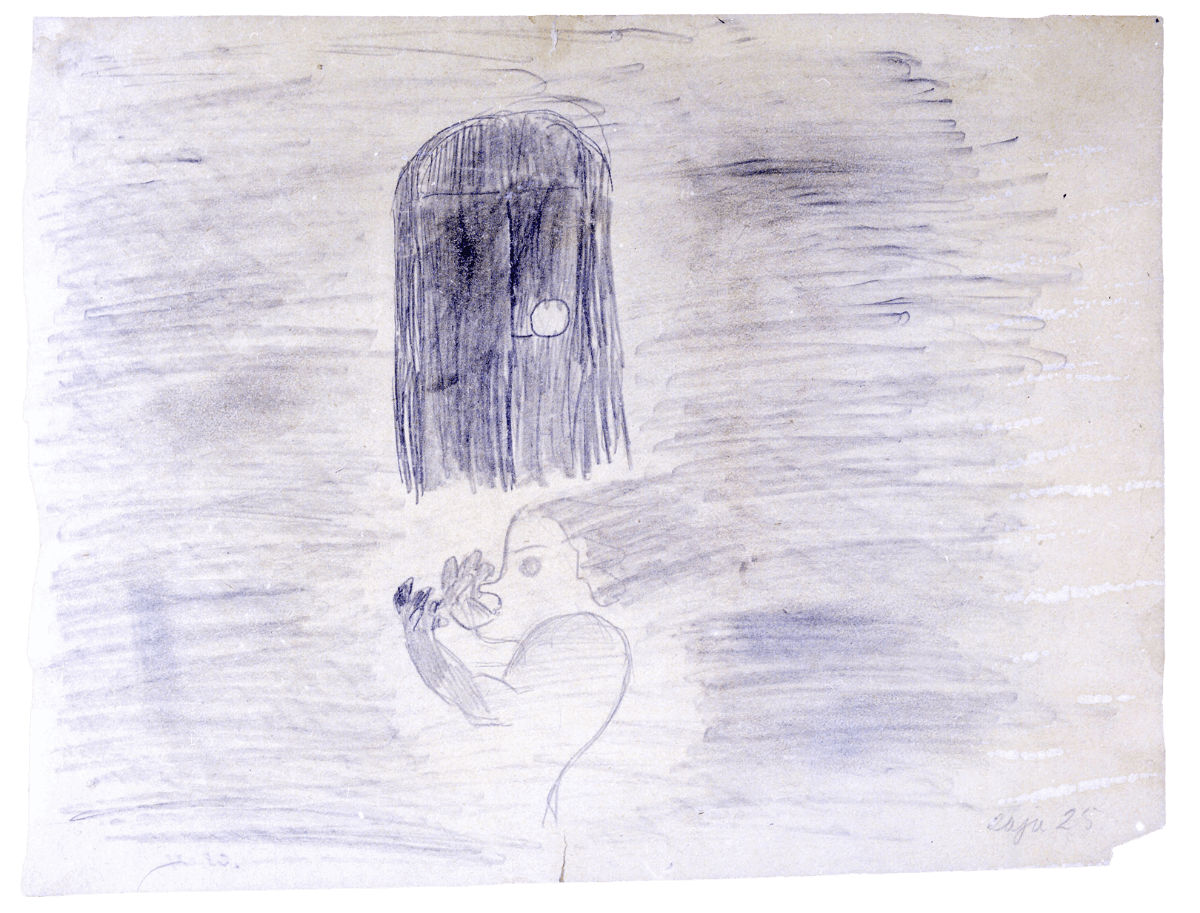

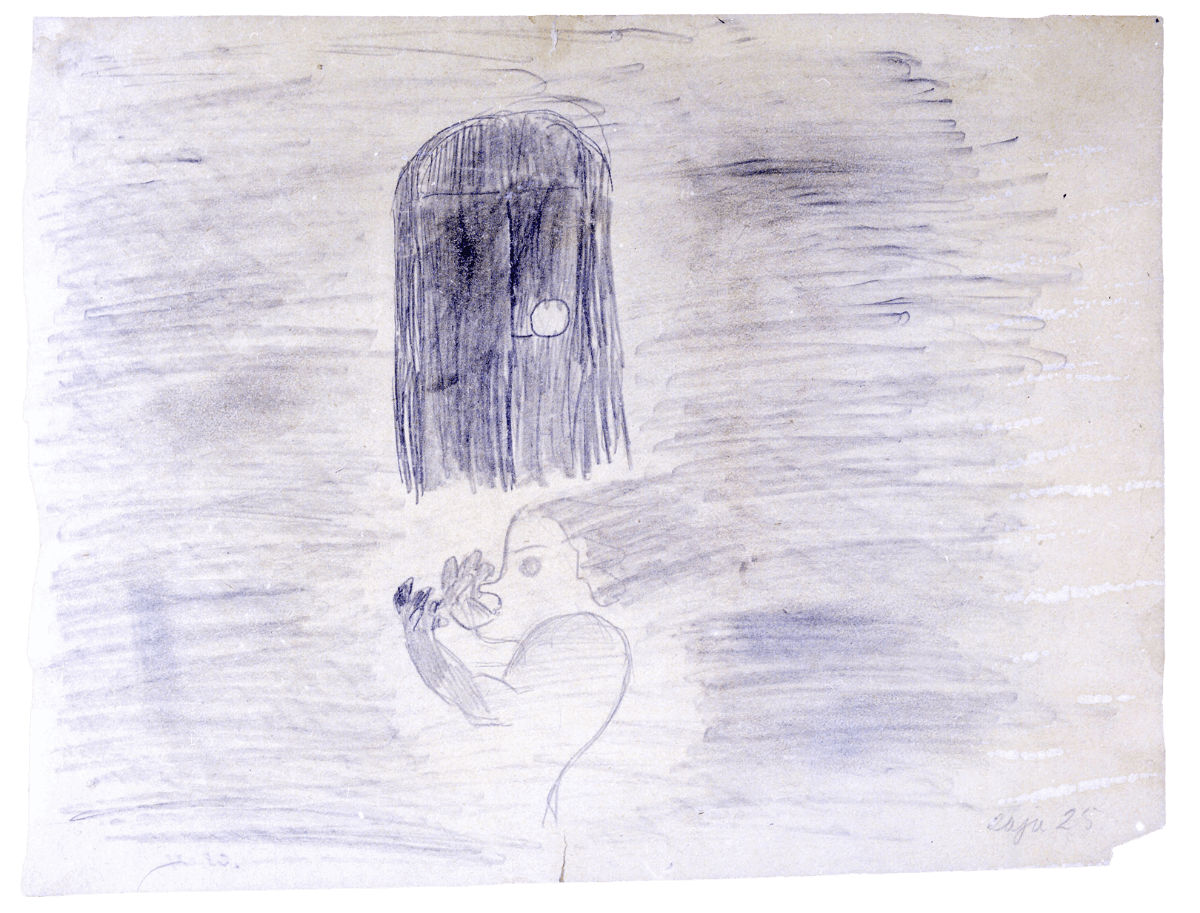

“My father has been killed, and I’m all alone. It’s almost night, but I have nowhere to go home.” The dark pencil drawing of the Star of David on the chest of the person being hanged reflects the boy’s anger.

This boy drew three pictures and all show the camp in pencil. It seems that no matter how much Friedl encouraged him to “remember the good times and draw happy pictures,” he could no longer do so.

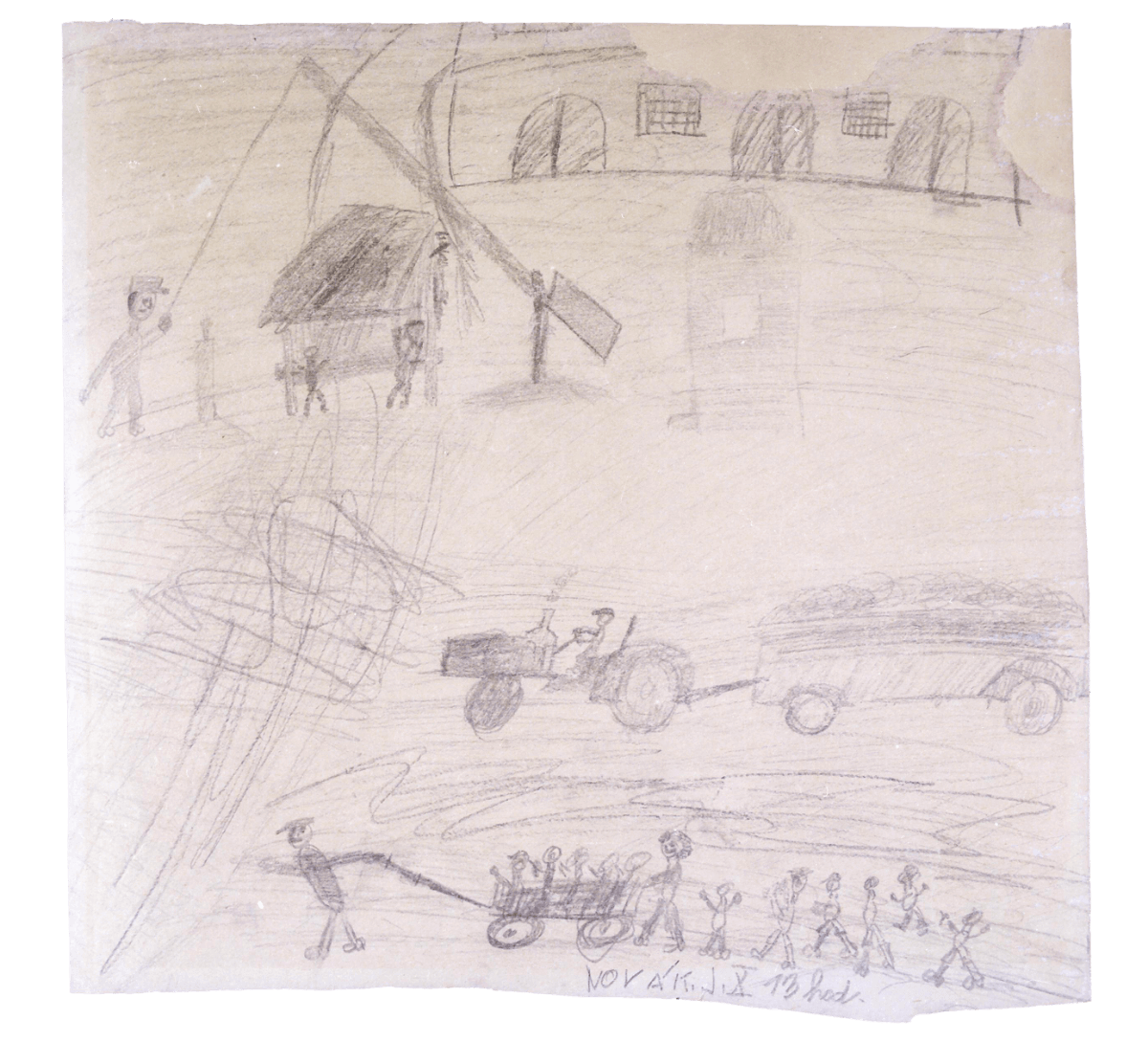

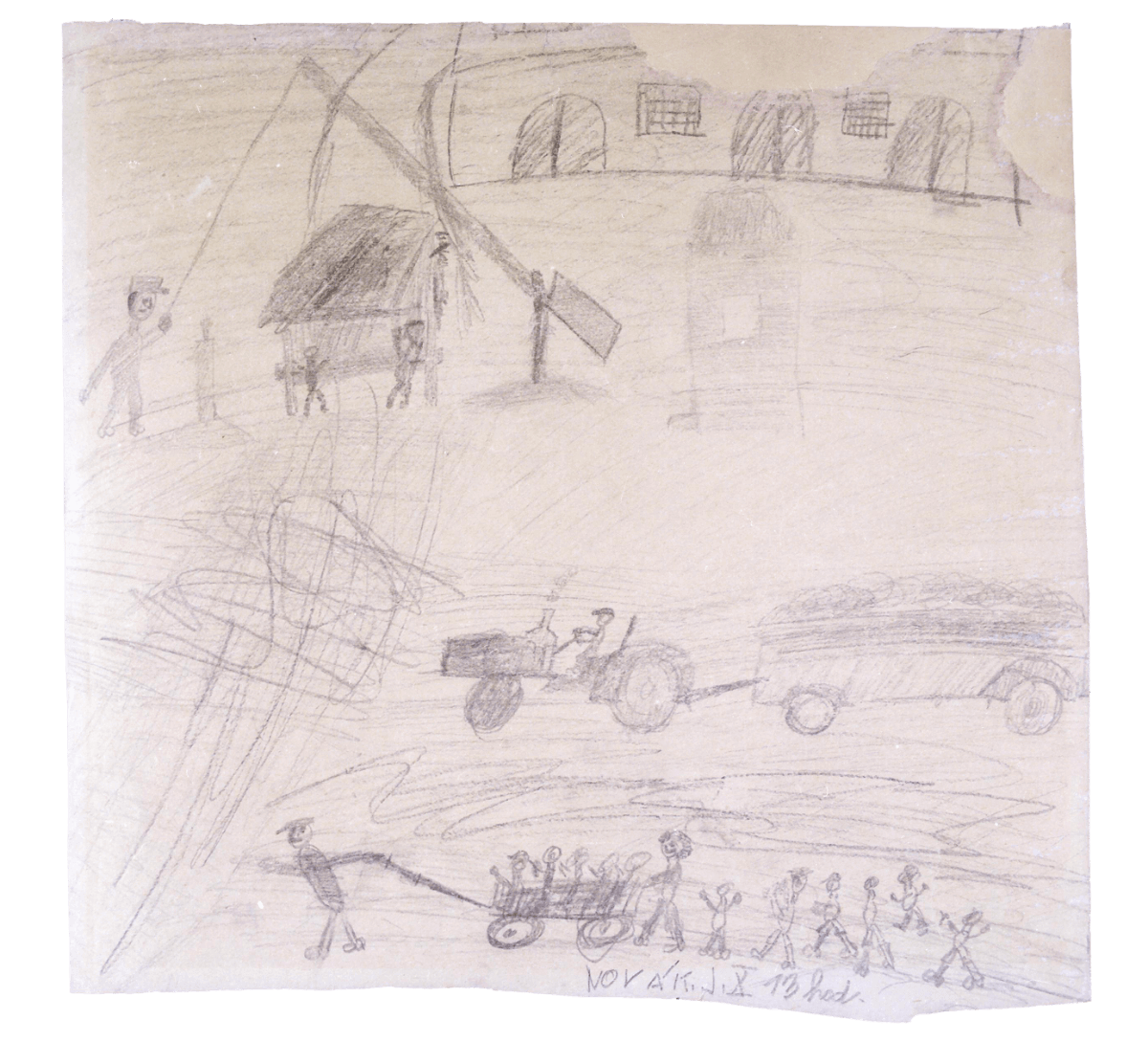

The boys were working carrying lumber and bricks, while the adult men were building new barracks nearby.

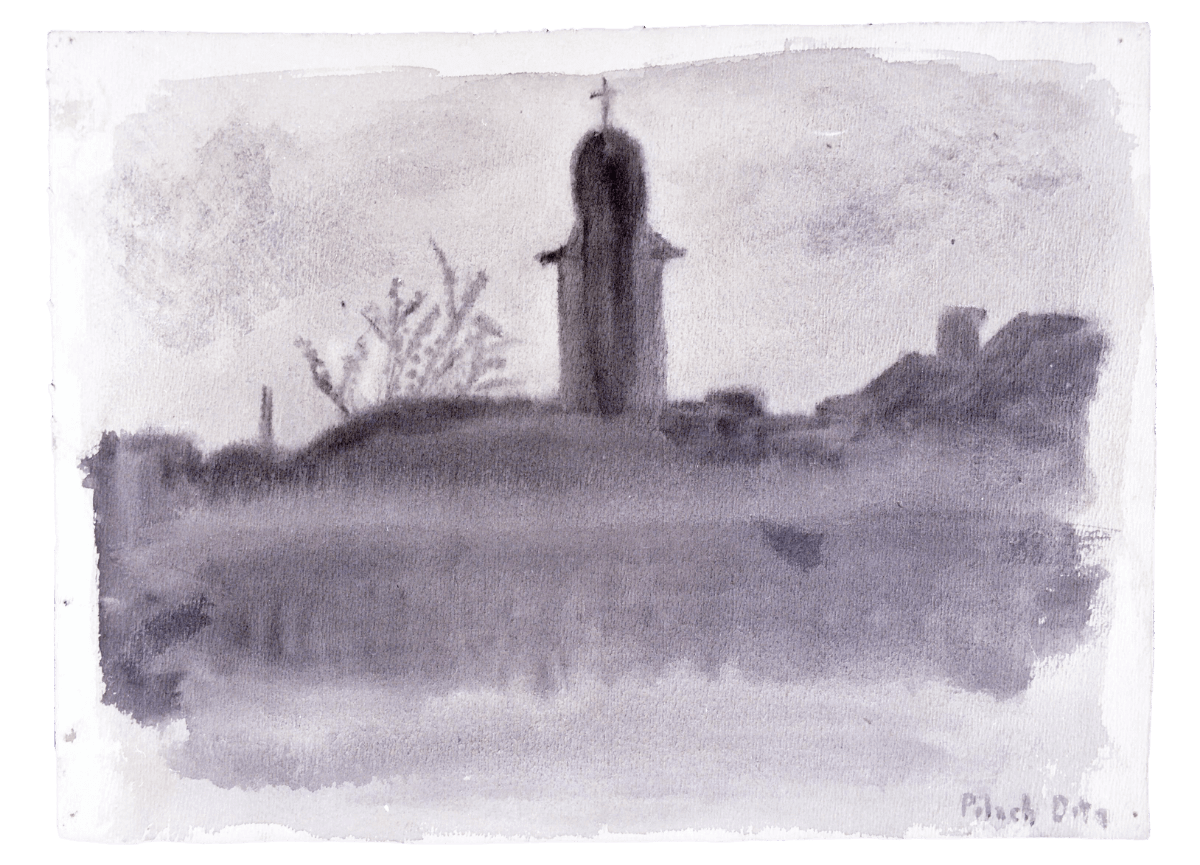

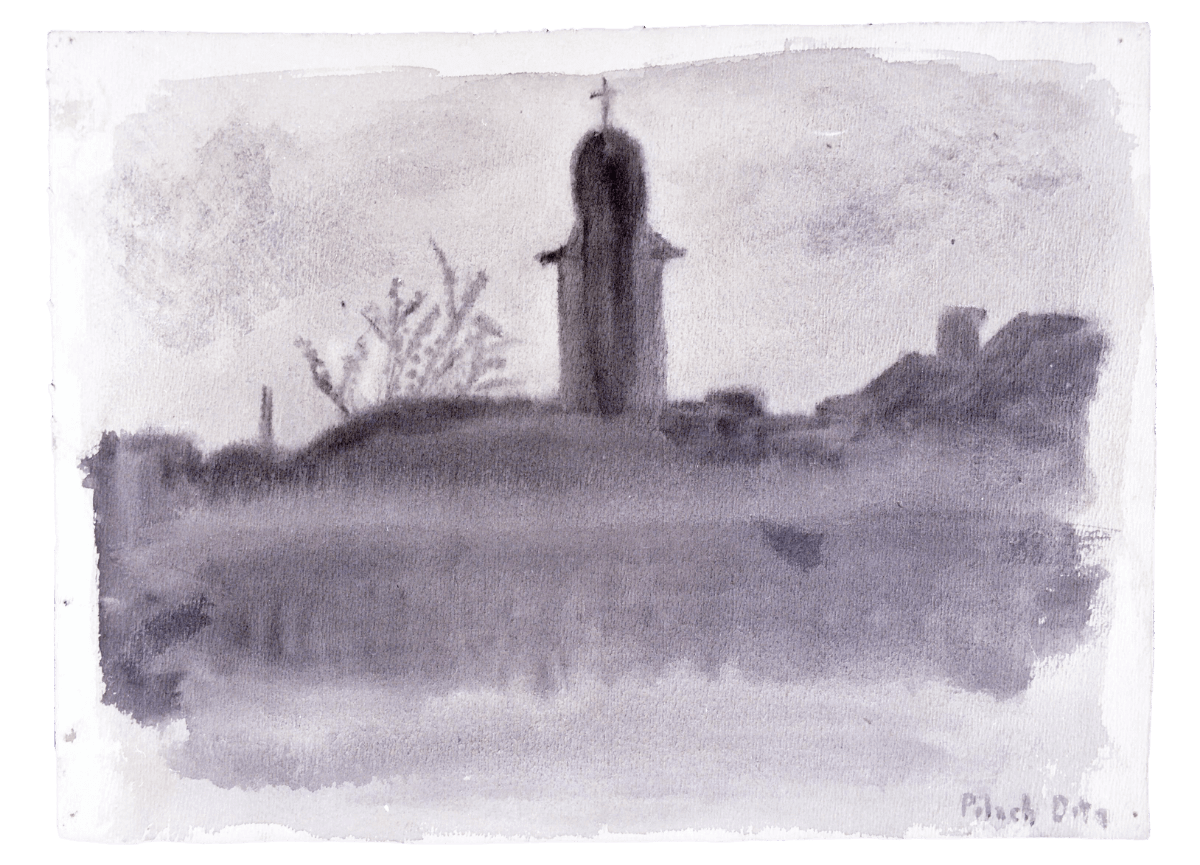

In the first art book (Italy, 1985), I (Michiko Nomura) saw, this drawing was listed as “artist unknown.” Dita’s name at the time was Edita Polachova, but she had often written it as “Dita” since her school days, which is probably why the artist’s name was unknown. In the late 1980s, an exhibition titled “Friedl Dicker & her Pupils” was held in Israel, and Dita went to see the exhibition and revealed that it was her drawing.

She was the first person to tell me about her experiences, and with her help, I was subsequently able to meet with five other survivors. “I am alive, so it is my duty to tell,” Dita said, “Everyone’s been killed, and even if they wanted to talk, they couldn’t.”

I (Michiko Nomura) received 150 photographic films from the Jewish Museum to make replicas for the exhibition in Japan, and this was one of the pictures that stuck in my mind. I discovered that the drawing’s author was living in Prague, and after several rounds of negotiations, a meeting was arranged. Of course, what I only wanted to ask was what the drawing was about, but Raja did not answer that question and started talking about something else. Although, fortunately, Raja and I became good friends and met several times afterward, we always talked about things that had nothing to do with the drawing.

Raja told me many stories. For example, the morning ration was very bad brown water called “coffee”; the straw bedding spilled when they pulled it over each other; and she once stole tomatoes and ate them while working in the fields, which was the girls’ job (if found, of course, she would be punished—some children were shot for stealing potatoes).

On the day I told her that I could not come to Prague for the time being due to the exhibition in Japan, she casually said, “So, today, let’s talk about the separation from my mother,” and began her story.

“One day, it was 1944. My mother, whom I hadn’t seen for a long time, came to our home. At that time, not many people still lived in our ‘Girl’s Home.’ I was so happy that I jumped on my mother. Then my mother said she had come to say goodbye and that she had to catch the freight train the next day. I was filled with sorrow. I had been trying to do my best until I could see my mother, even though I was going through hard times.

I went to the German military office because I knew that I wouldn’t stand it any longer if my mother left me. I asked them, ‘Please get me on the train tomorrow.’ At first, they said, ‘No, no, no! You are the leader of the fieldwork, aren’t you? You should stay here.’ But I begged them repeatedly and desperately to please. Finally, they said, ‘If you want to go so badly, go!’

So, the next morning, I ran to the freight train. You know, no platform, just the rails of the track. It was a long train. Dozens of freight trains that looked like just black boxes were lined up in a row. I ran, calling out loudly, ‘Mom, Mom!’ Then I heard my mother’s voice coming from one of the cars.

‘Raja, your mother is here.’ She looked out from among the people and extended her hand to me and I struggled up the ramp to grab her hand. Then a German soldier on patrol came. He said, ‘Hey, what are you doing? You’re not on the list, aren’t you? Get off!’ He grabbed my arm, and I fell down. I rolled over, and as I was getting up, the heavy wooden doors closed in front of me, and the German soldier bolted the door... and the train started moving. That was the last train from Terezín to the ‘east’ (*Auschwitz). And I survived.”

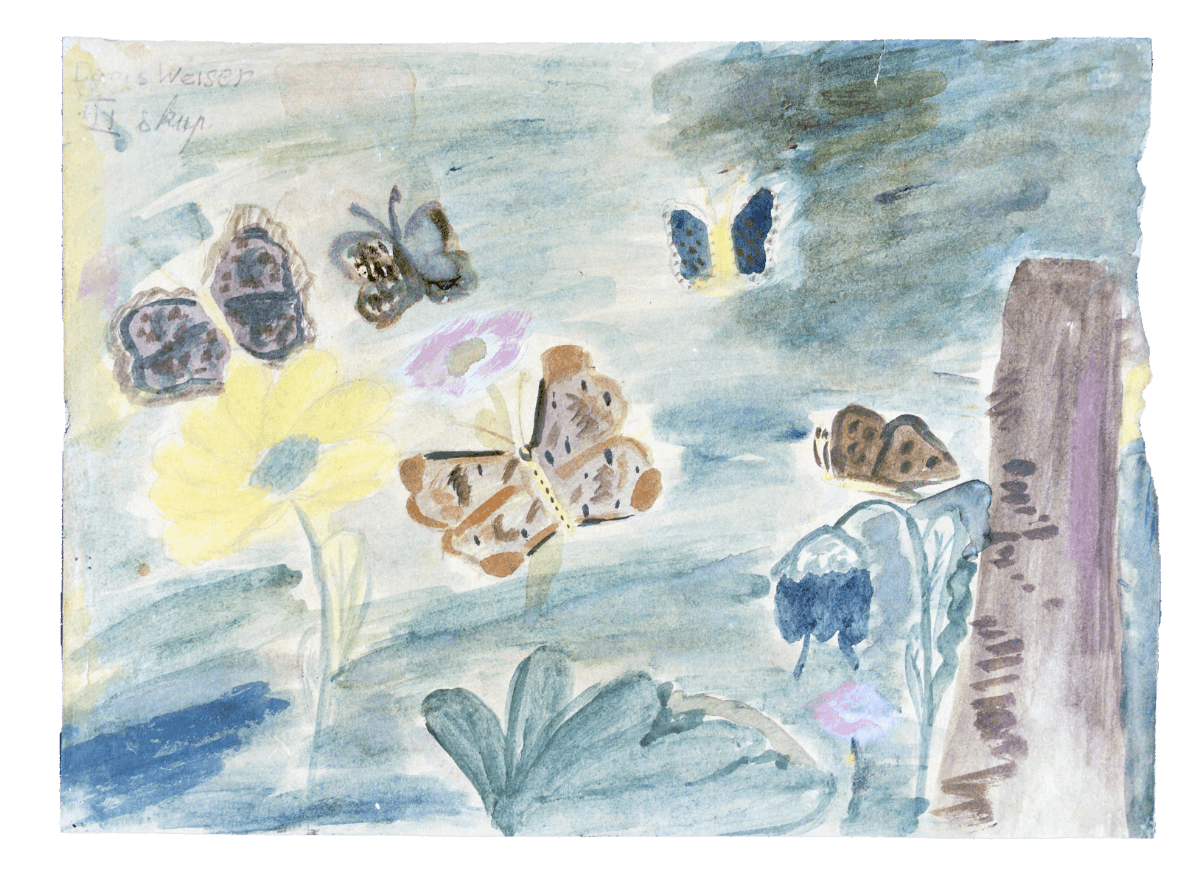

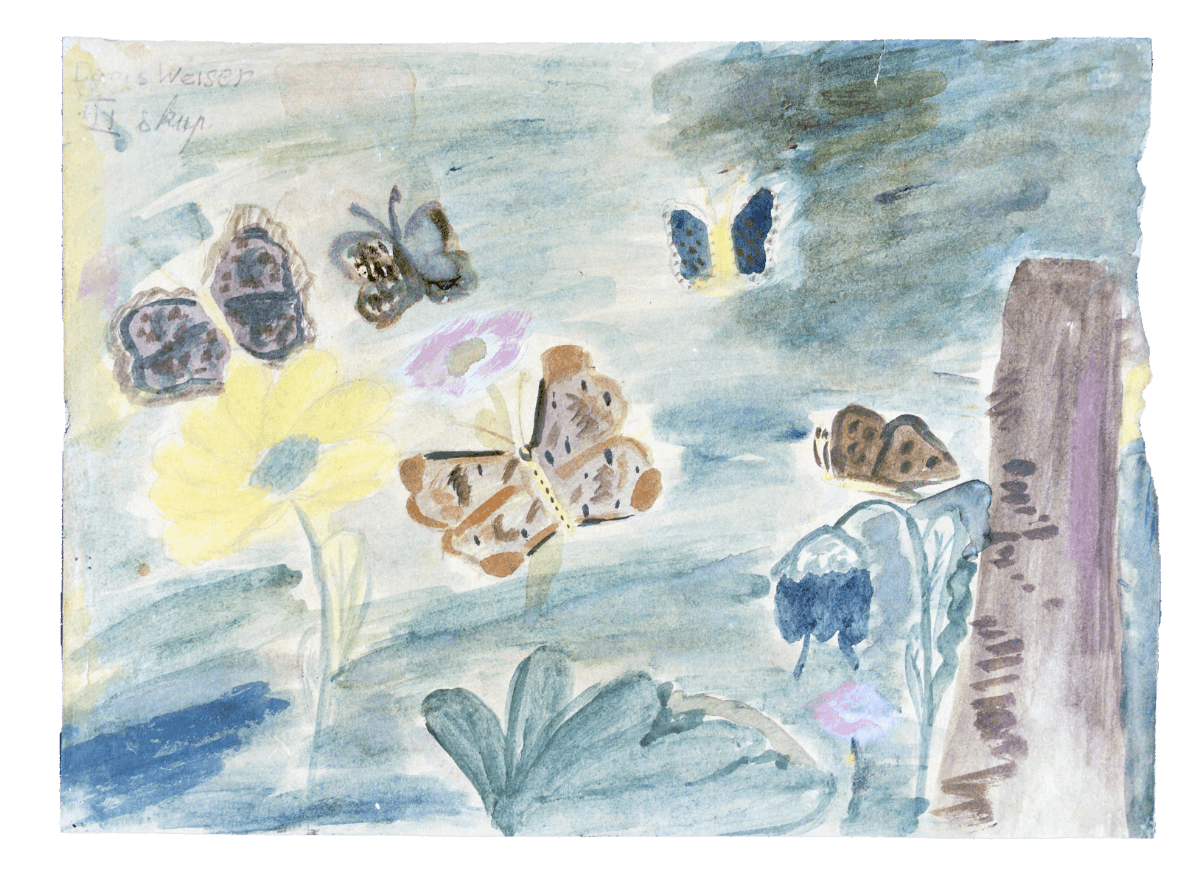

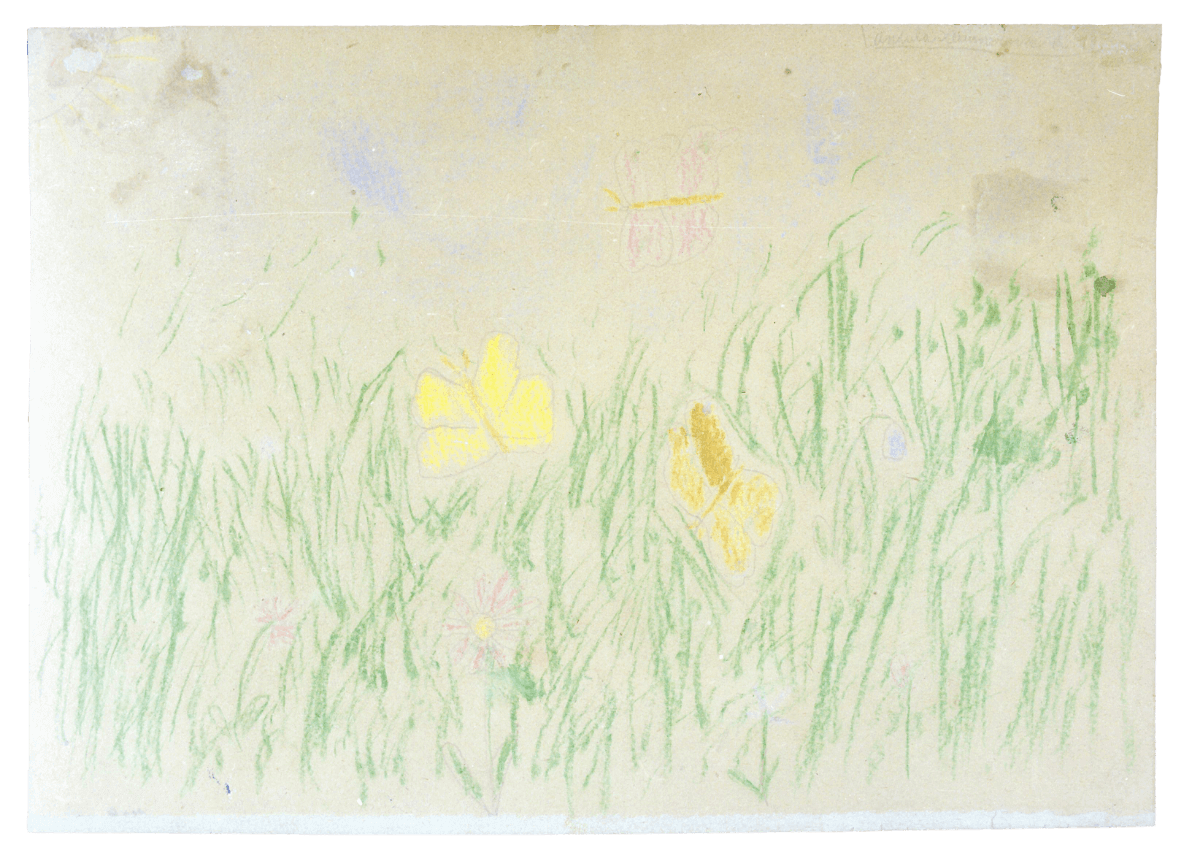

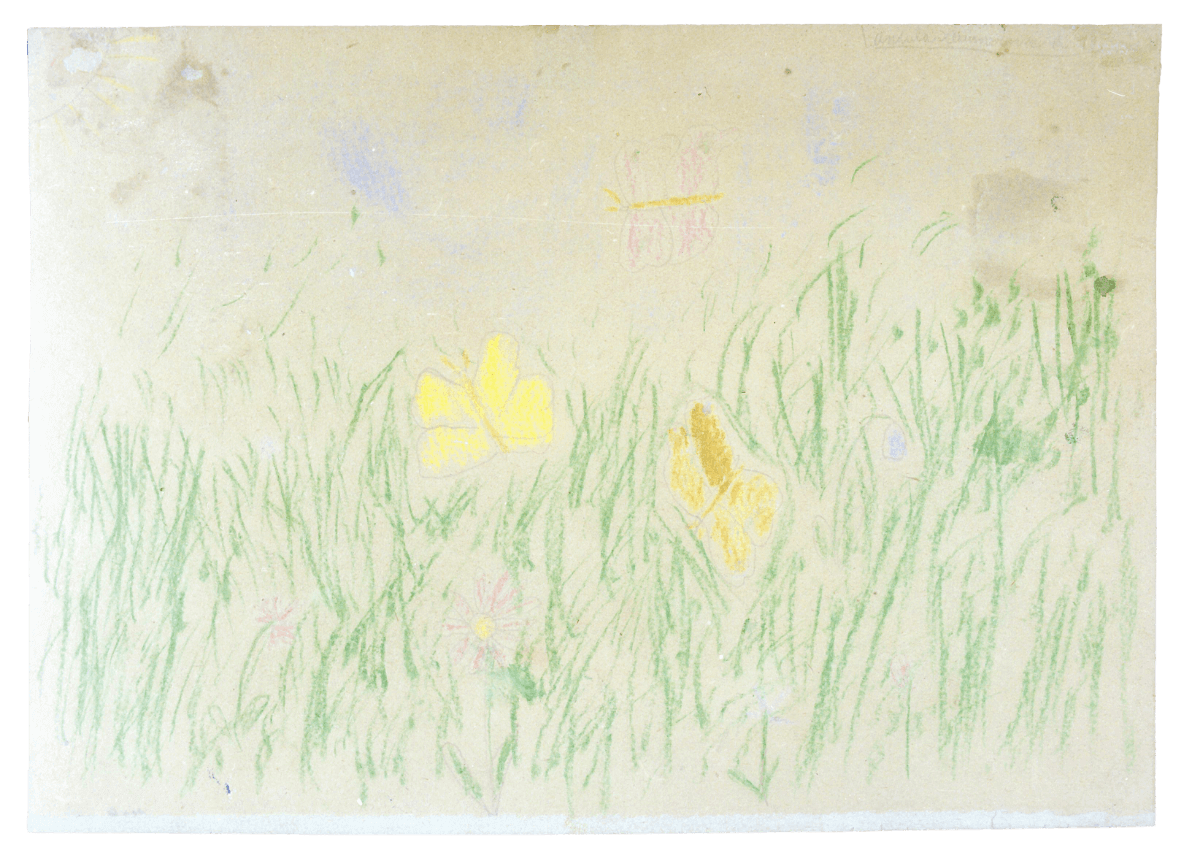

There are many drawings of flowers and butterflies. If they were butterflies, they would be free to fly outside; they could go beyond the high walls to the fields with beautiful flowers or to the children’s beloved home. The children probably entrusted such a dream to the drawings. Among them, this picture is used in various places and has become a symbolic picture of Terezín.

Such yellowness was bitter and blinding

― Omission ―

That last one was the last one.

There are no butterflies, here, in the ghetto.

A boy named Pavel Friedmann left behind the above poem.

In an art class at an elementary school, this drawing was discussed, and the students made many comments, such as “Not very good,” “If you are going to draw flowers, you should draw a lot of them in prettier colors,” and “It is weird that butterfly looks like a human face.”

Then I (Michiko Nomura) mentioned the Terezín Ghetto, where this picture had been painted, and the fact that the child who had drawn this picture was killed at Auschwitz. Afterward, one of the students was asked for his impressions again. He stepped in front of this drawing, bowed his head, and apologized, saying, “I’m sorry about as I said earlier. I laughed at your funny butterfly face, but you wanted to be a butterfly, right? You wanted to become a butterfly and fly far away. So, you drew your face on the butterfly.”

There are many drawings of flowers and butterflies. If they were butterflies, they would be free to fly outside; they could go beyond the high walls to the fields with beautiful flowers or to the children’s beloved home. The children probably entrusted such a dream to the drawings. Among them, this picture is used in various places and has become a symbolic picture of Terezín.

Such yellowness was bitter and blinding

― Omission ―

That last one was the last one.

There are no butterflies, here, in the ghetto.

A boy named Pavel Friedmann left behind the above poem.

There are many drawings of flowers and butterflies. If they were butterflies, they would be free to fly outside; they could go beyond the high walls to the fields with beautiful flowers or to the children’s beloved home. The children probably entrusted such a dream to the drawings. Among them, this picture is used in various places and has become a symbolic picture of Terezín.

Such yellowness was bitter and blinding

― Omission ―

That last one was the last one.

There are no butterflies, here, in the ghetto.

A boy named Pavel Friedmann left behind the above poem.

There are many drawings of flowers and butterflies. If they were butterflies, they would be free to fly outside; they could go beyond the high walls to the fields with beautiful flowers or to the children’s beloved home. The children probably entrusted such a dream to the drawings. Among them, this picture is used in various places and has become a symbolic picture of Terezín.

Such yellowness was bitter and blinding

― Omission ―

That last one was the last one.

There are no butterflies, here, in the ghetto.

A boy named Pavel Friedmann left behind the above poem.

There are many drawings of flowers and butterflies. If they were butterflies, they would be free to fly outside; they could go beyond the high walls to the fields with beautiful flowers or to the children’s beloved home. The children probably entrusted such a dream to the drawings. Among them, this picture is used in various places and has become a symbolic picture of Terezín.

Such yellowness was bitter and blinding

― Omission ―

That last one was the last one.

There are no butterflies, here, in the ghetto.

A boy named Pavel Friedmann left behind the above poem.

There are many drawings of flowers and butterflies. If they were butterflies, they would be free to fly outside; they could go beyond the high walls to the fields with beautiful flowers or to the children’s beloved home. The children probably entrusted such a dream to the drawings. Among them, this picture is used in various places and has become a symbolic picture of Terezín.

Such yellowness was bitter and blinding

― Omission ―

That last one was the last one.

There are no butterflies, here, in the ghetto.

A boy named Pavel Friedmann left behind the above poem.

It is said that Friedl drew pictures of flowers for children who could not see them. “Here’s a violet, here’s a lily, and here’s a gerbera ... Listening to the teacher’s story reminded me of a flower shop I went to with my mother before. And then I was able to paint flowers,” said Dita Kraus, one of the survivors, who, at 93 years of age, still paints flowers in the Israeli seaside town.

“Now I only paint flowers. Back then, I saw so many dirty and ugly things, so now I don’t want to see such things. I want to paint only beautiful flowers.”