The encounter with the children’s drawings was entirely coincidental. In February 1989, My daughter and I were about to go on a trip together, just before her graduation from University. The destinations were Poland and Czechoslovakia, which were still socialist countries at the time. In Poland, which has a sad history of being annexed by other countries many times, I was thinking of visiting Auschwitz, but in Czechoslovakia, I was planning to visit tourist attractions.

The capital of Czechoslovakia is Prague, the city that Mozart loved and where Anton Dvorak and Bedrich Smetana were born. My daughter and I had circled many museums, theaters, and churches in our guidebook.

We were walking through Prague’s Old Town Square. The wide streets and squares were bursting with crowds. Every building on both sides of the street was decorated with the Czechoslovak tricolored flag and the red flag. The national anthem was playing, and a rally was taking place in the plaza. My daughter said, “I have no ideas, but there must be some big event today.”

I later found out that February 23, 1989 was the anniversary of the declaration of Czechoslovakia as a socialist republic. About 6 months later, a wave of the Reformist Movement erupted in Eastern Europe, and the Velvet Revolution took place in Czechoslovakia, changing the country’s system. The rally in the square, which my daughter and I saw, was the last commemoration celebrated by the socialist county of Czechoslovakia.

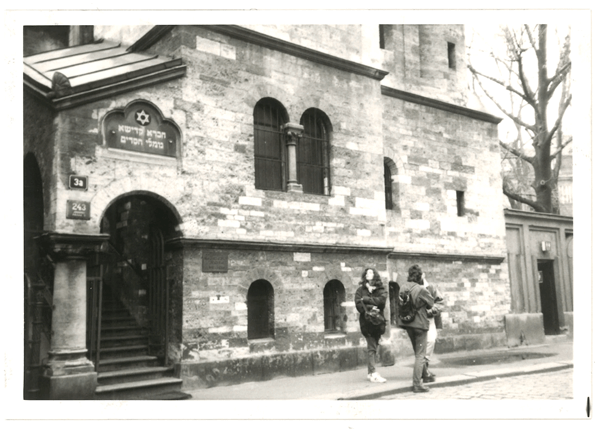

Avoiding the crowds, we took a side street. The former Jewish quarter is located in the road near the Moldau River (which in that country was really called the Vltava River). The door to the old-fashioned building was open, so I whispered, “Dobrý den.” A greeting I had just memorized from the guidebook the night before and went inside.

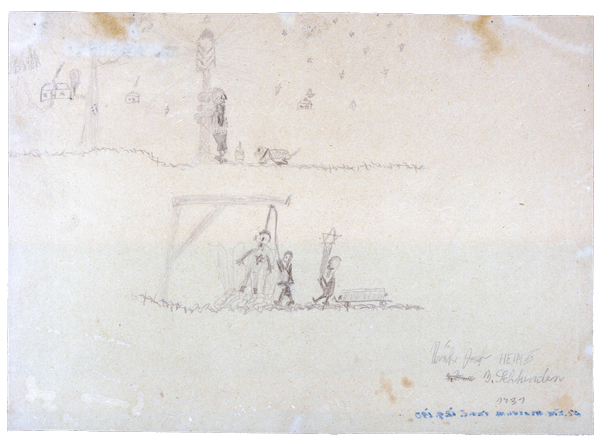

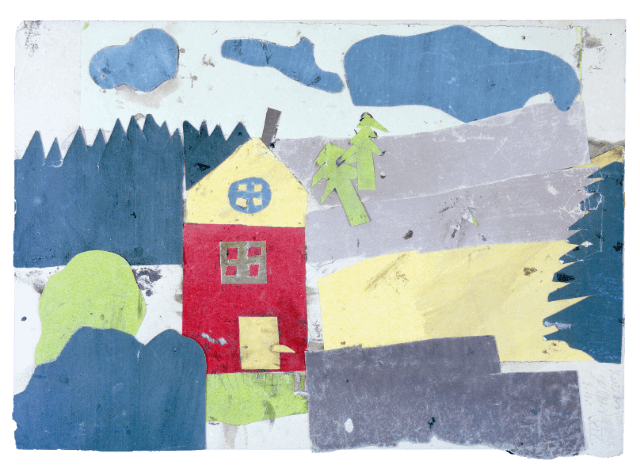

There, the drawings were on display. There were drawings of boys and girls lined up in front of a school building, a carriage full of hay, butterflies fluttering over red and yellow flowers, and drawings of ordinary children’s daily lives. That is what I thought until I saw one of the drawings, which, in the center, had a man about to be hanged; on his chest was the Star of David. In the upper half of the drawing was a boy standing leaning against an outside lamp.

“Oh, this is...” My daughter and I looked at each other.

We had visited Auschwitz a few days before. A few lines of text in a book I had bought there read as follows: “It was not only adults who were killed at Auschwitz. Many young lives were taken without mercy, and talents were also snuffed out before they could flourish. Fifteen thousand children who were drawing pictures and writing poetry in the Terezín Ghetto in Czechoslovakia were, too.” These drawings, which I was casually looking at, were exactly the children’s drawings described in the book.

That night, with a dictionary in hand, I read the flimsy French pamphlet I had purchased at the museum. By the time it was getting light outside, I understood the context in which the drawings had been made.