The meeting with Dita, a survivor of Terezín, was unexpected. In fact, the name Dita Kraus was not on the list of survivors I obtained in 1990.

Born in Prague in 1929, Dita was deported to Terezín Ghetto in 1941 at the age of 13 years. At the end of 1943, she was transferred to Auschwitz, and although she was sent to the gas chambers, she was eventually sent to Bergen-Belsen, where she saw the day of liberation. Because most of the people transferred to Auschwitz at the same time had been killed, and because she herself had married, changed her family name, and also changed her name from girlhood, research had lost track of her former name, Edita Polachova. In 1959, at the first exhibition in Jerusalem of posthumous drawings by the children of Terezín, Dita found out that her drawing was inscribed “Died in Auschwitz in December 1944?”

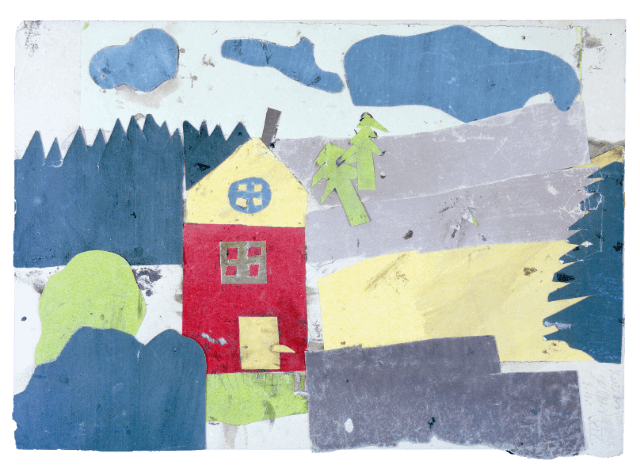

The drawing was in black paint, like a Japanese ink painting, and depicted a building with a church tower. The drawing class in Terezín was held for a year and a few months, from mid-1943 until the following fall. However, Dita was sent to Auschwitz in December of 1943; thus, it seems that she was not able to attend the drawing classes as often as other people.

She said, “I don’t remember how many drawings I did.” In fact, she couldn’t even remember when she had drawn the church. “I don’t remember when I drew it, but as soon as I saw it, I remembered that I had always seen this church.”

With a nostalgic look on her face, Dita said, “Friedl came to teach us to draw, of course. But more than that, I think she taught us hope for life. From the moment she walked into the children’s home, she was smiling and humming happily. I think it was enough to make the children feel relaxed and open-minded. It may seem strange, but after three or four drawing classes, everyone began to get along with each other, which created an atmosphere of mutual support. Until then, everyone had been silent ... Friedl brought several art books to the camp.

One night, three of us children who liked to draw were invited to her room; this was not allowed, and if we were found, we would be punished. She showed us her art books. There were so many wonderful paintings in beautiful, many different colors, landscapes, still-life paintings, and figures. There were also historical drawings from the Middle Ages. The one that made the strongest impression on me was Van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers.’ She told me that the yellow of this flower had red and blue colors in it; that’s why they look like such a shining sun. I thought that I wanted to paint a picture like that someday.”

Dita’s words shook me to my core. I realized that the children’s drawings were so bright, lively, and beautiful despite the harsh conditions in the camps because someone had told them that tomorrow would be a better day and because they were able to believe it.

I felt as if I had been taught the extent to which a wise and courageous adult’s presence can have a profound impact on children.

In December 1943, Dita and her parents were transferred to Auschwitz.

“My father died two weeks later, of starvation. When I was in Terezín, I was not sure that being sent to the ‘east’ meant death. There were rumors that it was a terrible place, but I was skeptical because the German troops said that they were sending us to a ‘new and better settlement.’ But every day after we arrived at Auschwitz, we saw the big chimneys belching flames, spreading black smoke and stench. Even as a child, I could see that many people were being killed and burned one after another.

I had heard rumors that at Auschwitz, a selection was made of people to be kept in the labor force and those to be sent to the gas chambers and that people between the ages of 16 and 40 were admitted into the labor force. They looked at each person’s complexion, physique, and the way they walked to select those who was suitable for physical labor. My mother was two people ahead of me in the line for selection. When I thought it would soon be our turn, my mother turned around and said, ‘Dita, 16 years old.’ I did not know what she meant for a moment, because I was 15. But when it was my mother’s turn, I heard her say loudly, ‘I’m 37 years old,’ despite being 42. Then I realized and straightened my back to look as healthy as I could and answered in German, ‘I’m 16 years old.’”

After passing through the life-and-death selection process, Dita and her mother were among only 1,000 women who made it out of Auschwitz alive to join the labor force. Packed onto a freight train for livestock, they arrived in Hamburg, Germany. There, their work consisted of clearing bricks from bombed-out buildings and building bunkers and air-raid shelters. “It was hard work using shovels and pickaxes. My hands were covered in scratches from the pieces of bricks. Some of us had frostbite and shoe sores from our flimsy shoes, and there were blood stains after we walked.”

The barracks were unsanitary, full of bedbugs, fleas, lice, and rats; there was no change of clothes, no laundry, and only one or two buckets used as toilet bowls in a room crammed with more than 100 people. A single personal bowl became a dish for getting soup during the day and a toilet bowl at night. It was no wonder diseases were so widespread. Even after enduring hard work, hunger, and disease, inmates were sometimes killed at the hands of SS members or camp supervisors. Sometimes they were killed as punishment and or as targets of boredom ‘games.’”

Next, Dita and her mother were sent to Bergen-Belsen. It was the worst place ever as Germany was losing the war. The ghetto had lost most of its functionality as a concentration camp and did not even have triple bunk beds; thus, they had to sleep on the floor.

“We ran out of soup rations. The next day, we didn’t get a crust of bread all day, and the day after that, we ran out of water. There was a water tap in the camp, but it only produced muddy, brown water. People died one after another. Some people had diarrhea and died on the road they had crawled out on to go to the latrine. After a few days, the camp was covered with dead bodies—they had had no strength to go to the latrine and had to crawl to find a place to defecate. Although we encouraged each other to survive somehow, the morning when we thought we were at the end of our lives, we heard a loudspeaker’s voice. They were repeating the same thing in many different languages. ‘You have been liberated. We are the British Army, and we will take care of you.’”

While Dita was being taken to the hospital, her mother wrote letters to relatives and friends who were supposed to be in Prague and Palestine. She wrote “We will be home soon” and “We look forward to seeing you.” Dita was finally beginning to feel that she had survived. However, “One day, my mother went to see the doctor because she had a stomachache. When I was finally able to walk and visited her, she was lying in bed and looked very distressed. The next day, she died of typhus.”

Dita returned to her hometown of Prague, hoping to find some relatives left there. She met a man who was also a survivor, married him at the age of 17, and soon after moved to the newly established state of Israel.

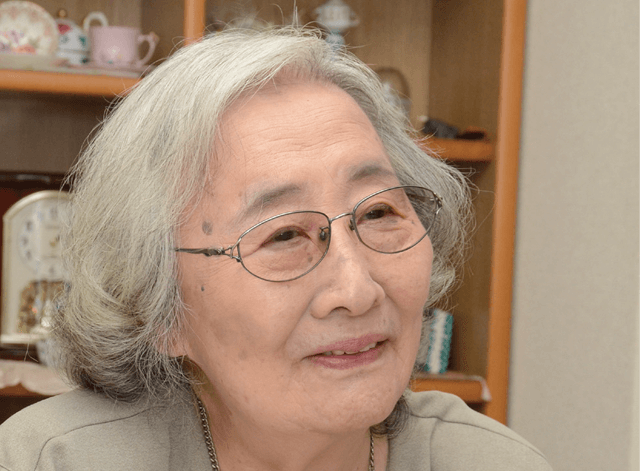

She is still painting pictures. It’s all about flowers. “I only paint flowers. I have seen so many dirty and ugly things that now I only want to paint beautiful pictures.”

It has been 33 years since I met Dita. We exchanged letters and e-mails and met many times at her home in Israel as well as in Japan, where I invited her to an exhibition. She often uses the word “fortunately.” She said, “There were a thousand coincidences and a thousand fortunes to survive.”

Indeed, the more I learn about those days, the more I think I can only say how difficult it was to survive, and how fortuitous and lucky she was. In meeting the survivors, however, it seemed to me that those who had been able to endure that famine must have been naturally blessed with physical strength. I wonder if a slightly greater physical strength and a strong will to live had made the difference between life and death.

Dita will be 93 years old this year. Last summer, I received an e-mail saying that she had undergone major surgery, but she was invited by the government of her native Czech Republic to give a lecture on International Holocaust Day on January 27 of this year. The response was so great that I have received emails from her telling me that she has given several lectures at schools and libraries in Prague.

“It is the duty of survivors to tell their stories,” she says, and she is still very much alive and active.

Survived (93 years old, living in Israel as of May 2023)