In 1990, when I wanted to meet the survivors, no documents about them were available in the Jewish Museum in the Czech Republic at that time.

In 1991, however, when the investigation for the 50th anniversary of the liberation of the Terezín Ghetto progressed, 23 survivors were located, and I was given a list of them. They were located at various addresses in their native Czech Republic, Austria, Hungary, the United States, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Israel. People who were children at the time are now older. They will all be ordinary people, living peaceful lives. They may not be able to erase the memories of the past, but I suspect that they are trying their best to forget about it. It is very cruel to ask such people to talk about their past; it is no wonder that they refused, but I want them to talk about it.

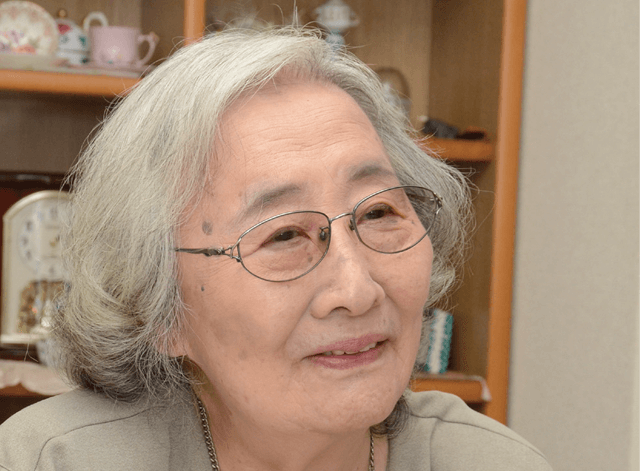

Listening to their stories was hard work. I felt very sorry, but I met the survivors and listened to their stories anyway. Many people have said to me, “You did a good job listening to their stories,” and asked, “How did you do it?”

I think one of the answers is the passage of time. Forty-five years had already passed since those hellish days. The children who had been placed in the children’s home at the age of 10–15 at the time were now 60 years old.

“I had never told anyone in all these years. Not my children, not my grandchildren,” one of the survivors said, “But I was just beginning to think that it was about time I told someone.”

Another answer would have been that I am Japanese and went to visit them from a distance. Before I went to talk to them, I wrote to each of them several times. Sometimes I visited them without receiving a response of approval. Although I visited them, I was unable to get to the point; I talked about myself, my children, and other things, and sometimes, I came back only to hear about their grandchildren. Then I visited them again the next day and the one after.

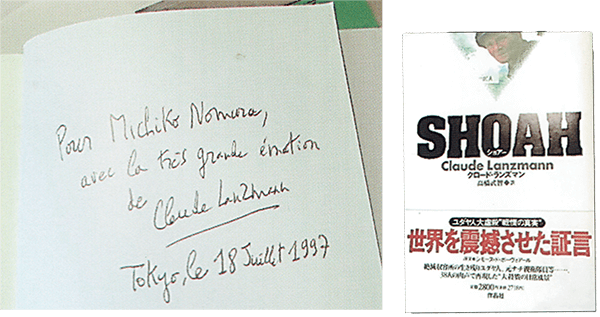

In the summer of 1997, I had the opportunity to interview Mr. Claude Lanzmann, the director of the documentary film SHOAH about the Holocaust, which is 9 hours and 45 minutes long. Many years ago, I went to Athens Francais for 2 days to see that film. It presents interviews with Holocaust survivors and Nazi soldiers involved in their murder; director Lanzmann himself becomes the camera and the microphone, repeatedly and mercilessly asking questions. From the moment I saw the film, I felt a kind of guilt—I could not do it, but I also felt that I would not be a full-fledged nonfiction writer if I did not go that far. That is why director Landsman was someone I admired, someone I wanted to meet at least once and with whom I wanted to talk about his interview methods if possible.

The outcome of that is still on the autograph I received for the thick SHOAH book. It says, “Pour Michiko Nomura, avec la tres grande émotion (For Michiko Nomura, with great emotion).”

Nonfiction writers and journalists in the world are many, and Dita and Raja have probably been interviewed many times. After 33 years of interaction, they still refer to me as their “friend.”

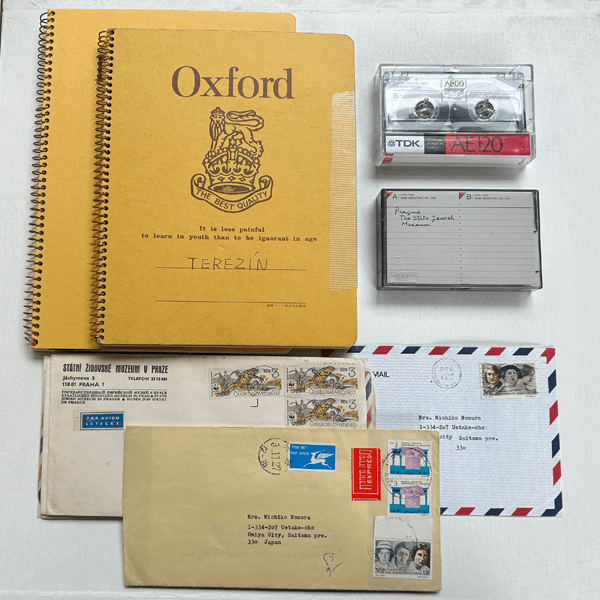

Now I have a cardboard box full of interview notes, cassette tapes of interviews, photos, and other materials given to me by these people, all of which were desperately brought out from the depths of memory by survivors. Although I need to organize my study room, I do not want to throw them away.

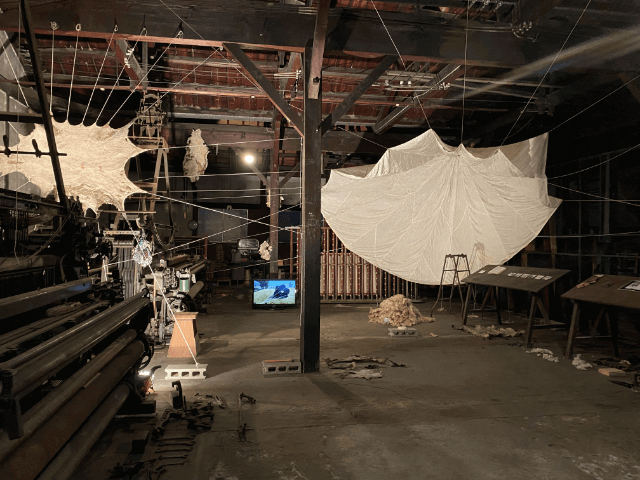

exhibition of actual goods :

The notebooks and cassette tapes of interviews reveal the trials and tribulations of years of interviewing. In 1990, when Ms. Nomura wrote manuscripts, she used paper and a fountain pen. Suffering from tendonitis, she wrote thousands of manuscripts. After using a word processor, she uses a computer nowadays.