Friedl was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1898 to Jewish parents. She studied at the School of Arts and Crafts in Vienna, where her talents were recognized, and moved to Germany in 1921 to study at the Bauhaus, the center of the nascent avant-garde art movement. There, she met nice colleagues and demonstrated her talent not only in painting but also in sculpture, stage design, stage costumes, textiles, graphic design, and other integrated arts. After graduation, she and her fellow moved to Berlin and opened a studio in her hometown of Vienna. Montessori Kindergarten, in which she designed everything from the desks and chairs to the toys used by children, became a major topic.

However, Germany’s political situation changed drastically. Hitler led the rise of the Nazis. Berlin, the previously free capital of the arts, became a city of fear, in which discrimination and abuse against Jews were rampant, and the number of Nazi followers also increased in Vienna.

Some of Friedl’s friends abandoned their homelands and went abroad. Both her Berlin workshop and studio in Vienna were destroyed, and Friedl, a Jew, was in danger. In 1934, Friedl moved to Prague. Life there was pleasant, and she painted several pictures of the beautiful city, the flowers in her window, and the neighbors with whom she had become friends.

However, because of Nazi Germany’s annexation of Sudetenland in 1938, Jewish life in the city of Prague was subject to various restrictions. Children were forbidden from going to school, riding trains and buses, and going to parks and swimming pools. They had to stay hidden. Friedl invited children to her house and taught them how to paint; if found, they were going to be punished.

Friedl’s friends from her days in Germany visited her once. They brought her passport, which they had painstakingly obtained for her. They persuaded her, “It’s not too late. Run away to a safe country. We don’t want to lose your talent.” However, Friedl refused: “There are children who only look forward to painting. I can’t just run away and leave them behind.”

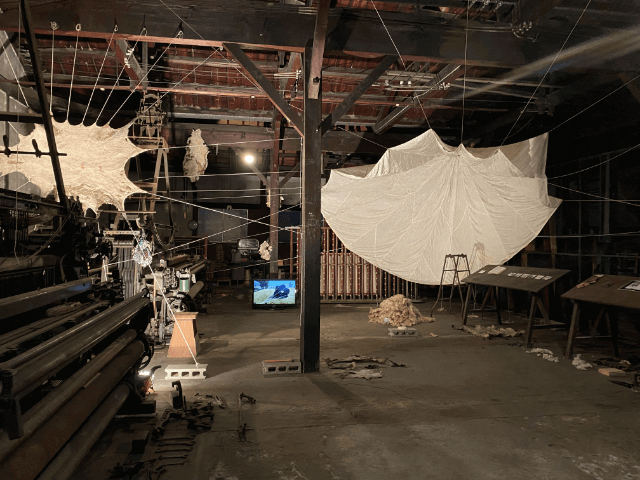

In 1942, Friedl was sent to Terezín.

“The word ‘fun’ has never been applied to Terezín’s memories, but if there was ever a time that was fun, it was during Friedl’s drawing class,” said both Dita and Raja, survivors of the Terezín camp.

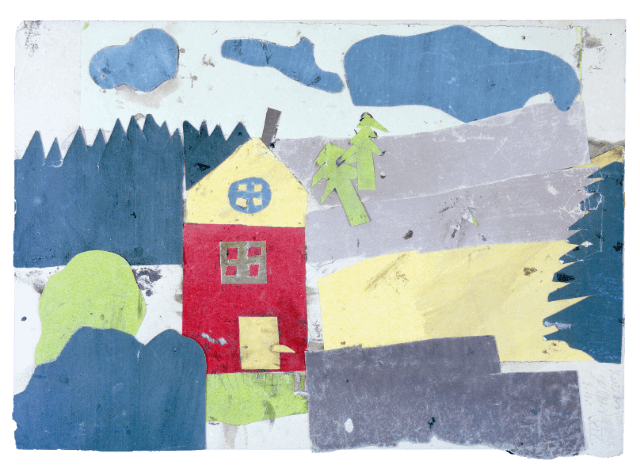

Friedl also studied art therapy. Through the drawings, she was able to read the children’s internal issues, such as their repressed mental states and anxious feelings, and talk to them appropriately. At the same time, she also developed a sense of individuality in children through her unique teaching method based on Bauhaus Education. She taught the children not only to draw but also to paste, cut, and collage, allowing them to create their own works of art with their own free imagination.

For a short while, the children began to smile, to regain their tender feelings, and to show their wonderful talents. This, however, meant nothing to Nazi Germany as they only considered children as labor force and sent those who were sick and weak to the “east” one after another.

On October 16, 1944, when Friedl was 46 years old, she herself was sent to the “east.”