In the Ghetto, children under the age of 10 were allowed to stay with their mothers, but after the age of 15, they were separated into boys and girls and treated like adults. In other words, 15,000 children between the ages of 10 and 15 were separated from their parents and divided into a “boys’ home” and a “girls’ home.”

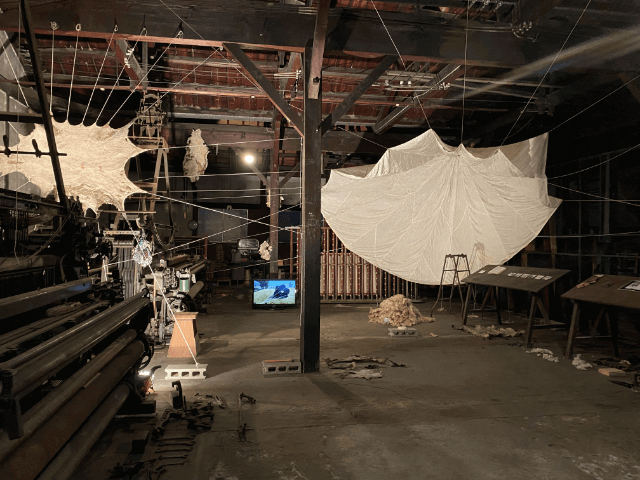

The rooms, which no longer have carpets or curtains, are lined with triple bunk beds but still not enough beds. Three or four children slept on top of each other in one bed “like sardines in a can.” There was only one straw bedding and one blanket. On cold nights, everyone pulled at each other so hard that the bedding soon ripped, and the straw came out. Even so, new bedding was not provided.

As for meals, breakfast was brown water called “coffee.” Lunch was a thin, salty soup with one ping-pong ball sized flour dumpling ; at night, it was a meager meal of salty soup and a small rotten potato or a slice of hard bread.

Despite such a meager diet, children were forced to work 10 hours a day, just like adults. They collapsed from overwork and malnutrition and were not given medicine or warm milk. When they were told to “no longer [be] of any use as labor,” they were put on a freight train to be taken somewhere else.

The destination was said to be “east.” Though nobody knew where “east” was at that time, even the children knew that it had a huge chimney that emitted stinky black smoke all day long and that nobody saw those who had been sent there again.

The children lost their smiles and just lived quietly so that the German soldiers would not be angry with them. Seeing these children, the adults discussed the situation.

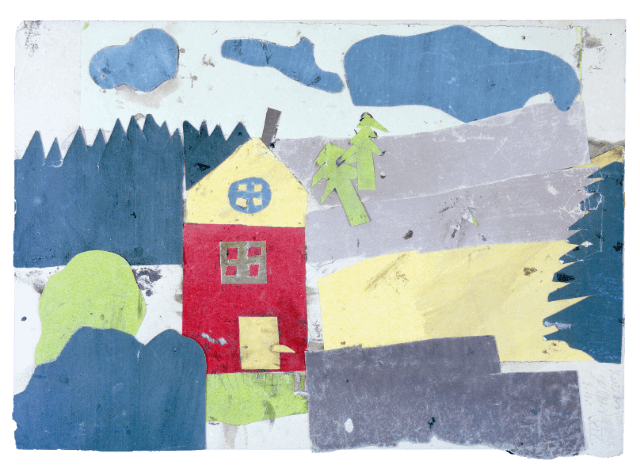

“We must bring back the smiles on those children’s faces”; “we must teach them that life is wonderful, even if for a limited time”; “what will give them the strength to live?” Then, an art class was opened in the camp. Several people came forward and said they would be teachers—former schoolteachers, musicians, poets, and writers. Among them was a female artist: Friedl Dicker.