When talking about children’s drawings, Mr. Willy Groag is an indispensable figure. A Jewish inmate himself, Willy was 28 years old at the time and spent 2 years and several months with the children as a caretaker at the “Girls’ Home.” Willy was asked for advice on various matters, such as “I miss my mother” or “I ran out of underwear, what should I do?”

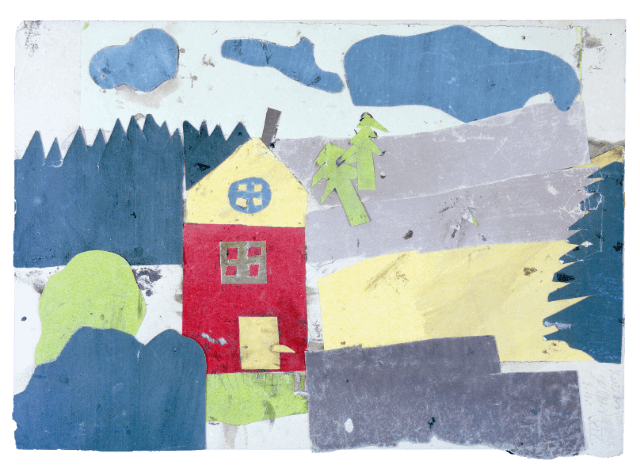

Loneliness, sadness, hunger, exhaustion, and the fear that their close friends would suddenly be taken away to the “east” and that tomorrow it might be their own turn… Willy was well aware that the drawing class was an emotional support for the children in those harsh days.

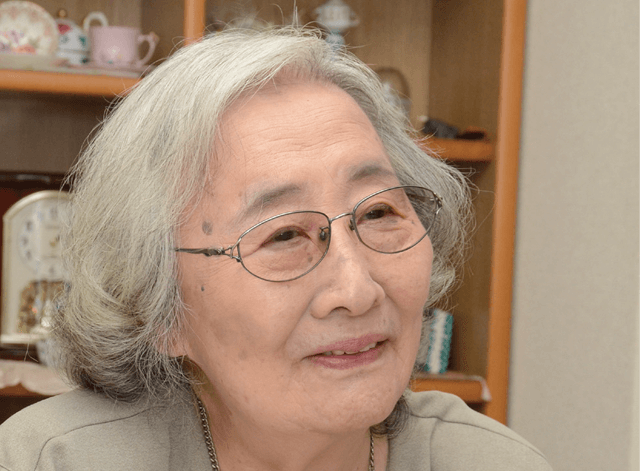

I first met Willy in November 1990 at the Beit Theresienstadt Museum in Givat Haim Ihud, Israel. He spent some time in Prague after the liberation of Terezín but soon moved to Palestine and participated in the founding of the State of Israel; he had become a grandfather with nine grandchildren.

“Terezín was liberated on May 8, 1945. It was sudden,” Willy told us, “There was terrible hunger and an epidemic of typhus. People were dying one after another without having to wait to be transferred, and the triple bunk beds where many children were sleeping folded up were empty. Most of the remaining children were malnourished or sick, and the only reason they were still there was because Auschwitz, where they were supposed to be sent, was no longer functioning. Only a hundred children survived until May 7, 1945, the day the war ended with the unconditional surrender of Germany.”

“During the withdrawal of German troops from Terezín, they collected many documents and tried to burn them. Among the piles of burned documents, I found children’s drawings. I had no idea why those drawings were in the German military office.

What I did know was that the children really seemed to be enjoying themselves, and their eyes were shining when they were drawing. I knew that most of the children who drew those pictures would never come back. I packed the drawings and the manuscripts of the poems placed near the drawings into suitcases that were in the warehouse. The warehouse was a treasure trove. Jewelry, silverware, fur coats… They were all taken from us Jews. Some of us even took them out. Even though we were liberated and could go home, we didn’t know whether we had a home or not. We were worried about how we would live, so it would be natural that we would try to bring home something expensive. But I knew I had to bring the drawings home with me.”

Willy walked back to Prague—60 kilometers away—with two large suitcases containing the drawings and delivered them to the Jewish community. As he had left Prague for Palestine, he did not know what had happened to the drawings.

The Jewish community, entrusted with the drawings, was busy with postwar processing. It was more than 10 years until the suitcases were opened again. One day, someone must have found the old suitcases in the basement and opened them. Inside were 4,000 drawings by children, most of which were signed by them. A list of Jews sent to Terezín and transferred to Auschwitz, testimonies of survivors… a frantic investigation was conducted by the Jewish community.

As a result of the investigation, many of the drawings were labeled with the name of the child who drew them, their date of birth, and the date they were sent to Auschwitz. Some of these drawings were shown in Prague. “In 1959, drawings of those children were shown to the public in Jerusalem. Some of the survivors stood in front of their drawings and wept. Many people have told me, ‘I am surprised these drawings survived.’ Some parents have had a child killed and only have one drawing as a memento.”

“Thank you, Michiko, for coming all the way from Japan for those children.”

I will never forget the warmth of his large hand that gently wrapped around mine after we talked.

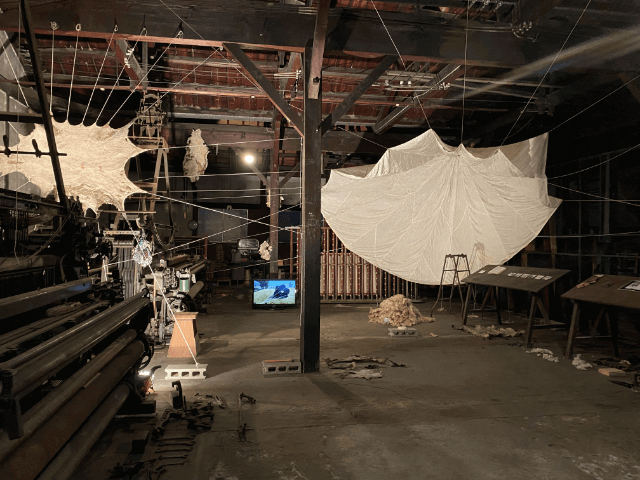

exhibition of actual goods :

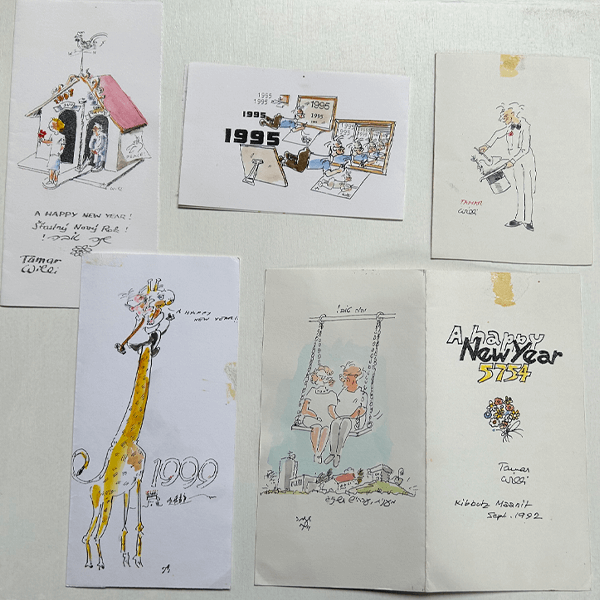

Willy loved drawing, and we continued to send cards to each other until he passed away. The bright colors and humorous touch remind me of his personality. The card with <<A Happy New Year>> written on it which was actually sent in June or July. The card sent in 1992 has the number “5754,” which must be the Israeli calendar. In addition to English, there is <<Slastny Novy Rok>> in Czech, with Hebrew letters below it. Willy speaks English, German, Czech, Hebrew, and Arabic.

Many of the other survivors also spoke several languages.

“It’s not what I wanted to learn, but I had no choice. In the camps, if I didn’t understand German, I couldn’t survive. After I was liberated, I came to Israel. Here, Hebrew is spoken. You are so lucky, Michiko, to be able to live with one language. I speak several languages and wonder where I am from.”