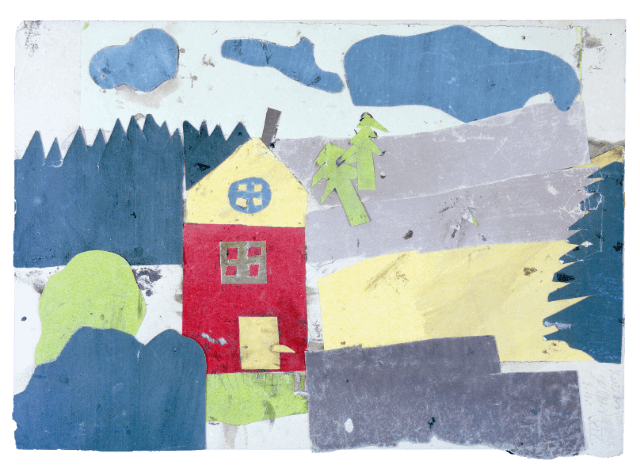

When I came across the drawings of the children of Terezín, I immediately wanted to show these to the children in Japan. When I learned about Ms. Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, who risked her life to open a drawing class in the Ghetto, I wanted to tell adults in Japan about it.

After 6 months, I was promised that I would receive a photographic film of the drawings, and in the meantime, I visited the Terezín concentration camp many times. I also visited Auschwitz (also called a “death factory”) where many children were sent and where their lives were taken. In both places, I bought every book on sale and read them with a dictionary. My head ached, and I felt sick, but it is still not enough. I must listen to the voices of those who have lived there; they should be there, but I cannot meet them. They refuse to see me because they don't want to remember those days.

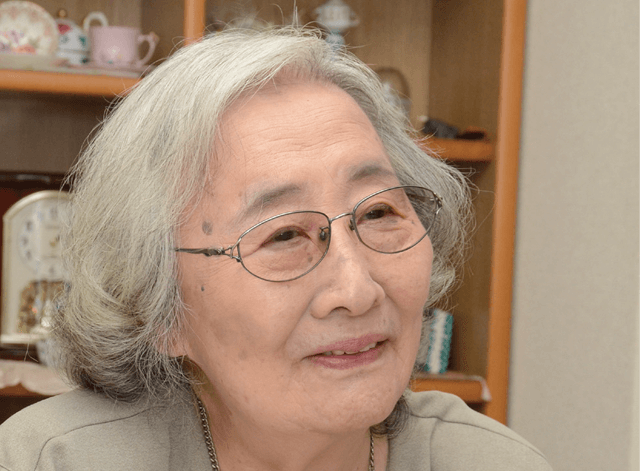

Yet I finally met a survivor from Terezín. She had been sent to Auschwitz but was fortunate enough to survive. When she had gotten there and off the freight train, she had seen things fluttering in the air like flower petals and noticed a strange smell ... even a girl of only 13 years of age knew immediately that these were burning enormous corpses. She had been shaved, had had numbers tattooed on her arms, and had then been sent to the Bergen-Belsen camp, where she had contracted typhus and had laid half-dead among the corpses until the war ended, when she was finally rescued.

It must be hard to tell, but it is also hard to listen. I struggled to say the words of the question. I stopped myself from looking at her arm with the number carved into it, but I have to ask. I cannot simply move on without knowing.

Dita Kraus said she would tell me, even though it would hurt. “It is the duty of the survivors to speak up, since everyone is dead and unable to speak.”