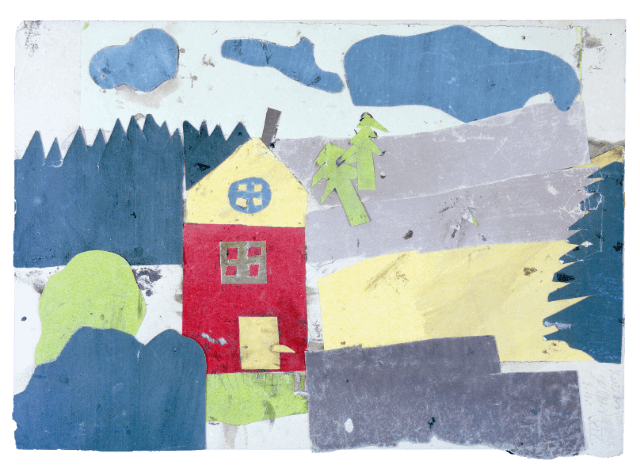

In 1989, when I saw the children’s drawings for the first time, I was moved by the signatures on many of the drawings. The museum in Auschwitz, which I had visited a few days earlier, had a lot of stuff on display. It said, “Some of the belongings of those killed here,” but we never saw the names or faces of those killed; a pile of glasses, but who wore them? The little red shoes, the golden shoes with the long, thin heels, perhaps worn when doing dance steps. Bundle of hair cut off in braided pigtails. No matter what I looked at, all it said was “the remains of many victims.” I hated that. I feel sad.

All victims had names, faces, and life stories, but they were all erased. Only the fact that there were so many victims was emphasized, and each person seemed to be buried in a pile of relics.

Yet the drawings of the children in the Terezín Ghetto had names.

“You have names. Whether the German soldiers call you by number or call you pigs, you all have names that your fathers and mothers lovingly gave you. Let’s write it down.”

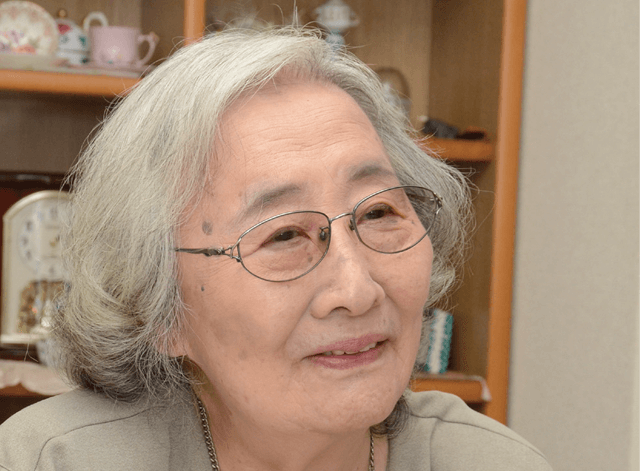

Willy Groag, who worked as a caretaker at the “Girls’ Home” in Terezín Ghetto, remembers well how Friedl used to talk to the children; he is the one who found the drawings left in Terezín and brought them to Prague.

He said, “Some of the children still couldn’t write well, so Friedl helped them.”

It was over 20 years after the war ended that research began on drawings made by the children. “I was asked to come and help with the research on the drawings. While I was working in a kibbutz (*an intentional community that was traditionally based on agriculture) in Israel at the time, I was given special permission to go to my home country. Fortunately, as the city of Czechoslovakia was not damaged by the war, there were still some Jewish materials left. In addition, the Nazis kept detailed records; thus, I thought that if I knew the names of the children, we could determine their whereabouts. But it was tough work.

I went through each of the 4,000 drawings one by one, reading and matching them with the documents, even though some of the signatures were not very good or only had nicknames. Anyway, most of the children were killed, you know. Ah… this child who was very good at drawing and this child who was a crybaby were killed, I was reminded of so many things that I couldn’t get on with my work. But I worked on it, thinking about how wonderful it was that Friedl had taught children to write their names. It took many years, but the authors of many of the drawings were identified. Still, there some are ‘author unknown.’ If you look closely, you will see that those are unfinished works. I guess they thought they would draw them up and write their names on them in the next class.”

Because I had heard his story, I have always treasured the nameplates when holding exhibitions in Japan. I asked the embassy to teach me how to read all the children’s difficult names, and I included their birthdates and the date they were sent to Auschwitz. Every time I gave an opening address, I would say this: “With the exception of a few, the drawings have name on them. The name of the child who drew it, the date of birth, and the date that he or she was sent to Auschwitz ......, many of whom were probably killed that day. I believe that each drawing is telling us something. Any of the drawings will be fine. If you find a picture that stands out, please call out the name of the child who drew it. Please remember the name.”